Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

www.shambhala.com

2020 by the Khyentse Foundation

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

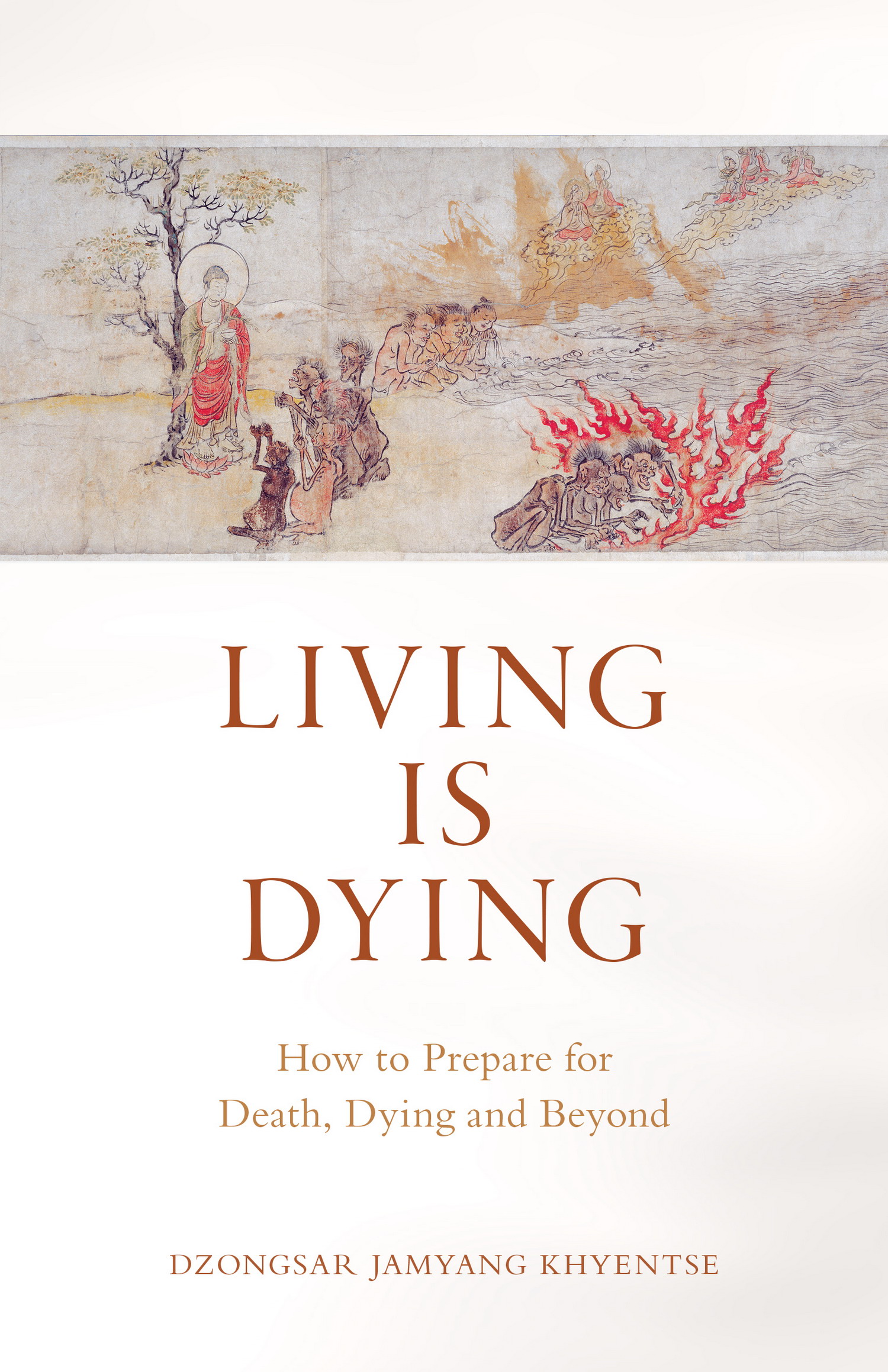

Cover design by Jamie Tipton

Cover art Kyoto National Museum

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Khyentse, Jamyang, 1961 author.

Title: Living is dying: how to prepare for death, dying and beyond/Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse.

Description: Boulder: Shambhala, 2020.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019022860 | ISBN 9781611808070 (paperback)

eISBN 9780834842717

Subjects: LCSH : DeathReligious aspectsBuddhism.

Classification: LCC BQ 4570. D 43 K 49 2020 | DDC 294.3/423dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019022860

v5.4

a

Contents

Preface

Death exists, not as the opposite but as a part of life.

H ARUKI M URAKAMI

T HE INSTRUCTIONS Buddhists are given during the process of dying, at the moment of death and after death are the same whether the person dies peacefully in their sleep at a ripe old age, or unexpectedly because the causes and conditions that lead to sudden death have matured.

The information that appears in this book is a very simple presentation of a specific and ancient tradition of Buddhist teachings that has been passed down through a long lineage of brilliant Buddhist thinkers, each of whom went to great lengths to examine death and dying in minute detail and from every angle. Their advice is particularly useful for Buddhists or those attracted to the Buddhas teachings, but it also provides valuable information for anyone who will die. Buddhist or not, if you are open-minded and curious, or contemplating your own death or that of a loved one, you may well find something in these pages that will help.

Everything that happens to us in life and death depends entirely on our accumulated causes and conditions. As each of us will experience physical death and the dissolution of the bodys elements quite differently, our journeys through the bardos will be unique. Therefore, any and all descriptions of dying, death and the bardos can only ever be generalizations. Nevertheless, once the process of dying has begun, to have a rough idea about what is happening not only goes a long way towards allaying our worst fears, it also helps us face death calmly and with equanimity. While most authentic Buddhist traditions offer essentially the same advice, as each has developed its own language and terminology some details may appear to differ; please dont misinterpret these variations as contradictions.

I should say a word about the inconsistent use of Sanskrit spelling and diacritics in this book. Usually, when Sanskrit appears in Roman characters rather than the Devangar script, diacritics are used to help the reader pronounce words correctly. As the study of Sanskrit is relatively rare, fewer and fewer of us are able to read diacritics. For some, the mere sight of all those squiggles and dots is confusing. Diacritics have therefore not been applied to the Sanskrit terms in the main body of the text or to the names of deities and bodhisattvas and so on, but some have been retained in quoted texts. Similarly, where quotations include Tibetan-style spellings of Sanskritfor example HUNG instead of HUM those spellings have been retained.

Ironically, although I am always so busy these days, at heart I am unusually lazy. Juggling these two extremes is quite a challenge, which is why I ended up writing much of this book on a social networking app. If my English is at least readable, it is thanks to Janine Schulz, and to Sarah K. C. Wilkinson, Chim Metok, Pema Maya and Sarah A. Wilkinson.

The framework of this book was created in response to a list of nearly one hundred very good questions about death that were gathered by various friends of mine. I would particularly like to thank my Chinese friends Jennifer Qi, Jane W. and Dolly V. T.; Philip Philippou and the Spiritual Care team at Sukhavati in Bad Saarow, Germany; Chris Whiteside and the Spiritual Care team at Dzogchen Beara; Miriam Pokora from the Bodhicharya Hospice in Berlin; and all those who attended the teaching at Schloss Langenburg.

I would also like to thank Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche, Pema Chdrn, Khenpo Sonam Tashi, Khenpo Sonam Phuntsok, Thangtong Tulku and Yann Devorsine for contributing their expertise; Adam Pearcey, Erik Pema Kunsang, John Canti and Larry Mermelstein for generously sharing their translations; Jane W., Chou Su-ching, Vera Ho, Florence Koh, Kris Yao, Paravi Wongchirachai, Seiko Sakuragi and Rui Faro Saraiva for their help and advice; Cecile Hohenlohe and her family, and Veer Singh and everyone at Vana for their kind and generous hospitality; Andreas Schulz for the original design of Living Is Dying; Nikko Odiseos, Emily Coughlin and everyone at Shambhala Publications for their enthusiasm and patience; and the artists Arjun Kaicker and Tara di Gesu for contributing their beautiful pictures.

Prince Siddhartha being driven out of his fathers palace by Channa

ONE

Will I Die?

F OR THE FIRST three decades of his life, Prince Siddhartha lived an idyllic existence behind the walls of his fathers vast palace. Universally loved and admired, the handsome prince married a beautiful princess, they had a son, and everyone was happy. But in all that time, the prince never once stepped outside the palace gates.

In his thirtieth year, Siddhartha asked his faithful charioteer, Channa, to drive him through his fathers great city and, for the first time ever, the prince saw a dead body. It was a terrible shock.

Will what happened to that man happen to me? he asked Channa. Will I die too?

Yes, Your Majesty, replied Channa, everyone dies. Even princes.

Turn the chariot around, Channa, ordered the prince. Take me home.

Back at the palace, Prince Siddhartha thought over what he had just seen. What was the point of being a king if not only his family but everyone on this earth had to live under the terrible shadow of the fear of death? There and then, the prince decided that, for everyones sake, he would devote his entire life to discovering how all human beings can go beyond both birth and death.

This very famous story contains a great many teachings. Just the fact that Prince Siddhartha asked, Will I die? is not only touchingly innocent, but also remarkably brave. Will I die? Must mighty Siddhartha, the future king of the Shakyas, whose destiny is to be the Ruler of the Universe, die? How many of us, from royalty to ordinary people like you and me, would even think of asking such a question?

The question may have been brave, but the princes reactionTake me home!sounds, on the face of it, a little childish. Arent adults supposed to deal with disconcerting news more maturely? But then, how many adults would bother asking, Will I die? And how many would then cut short a fascinating outing or any form of entertainment to examine and contemplate the answer?