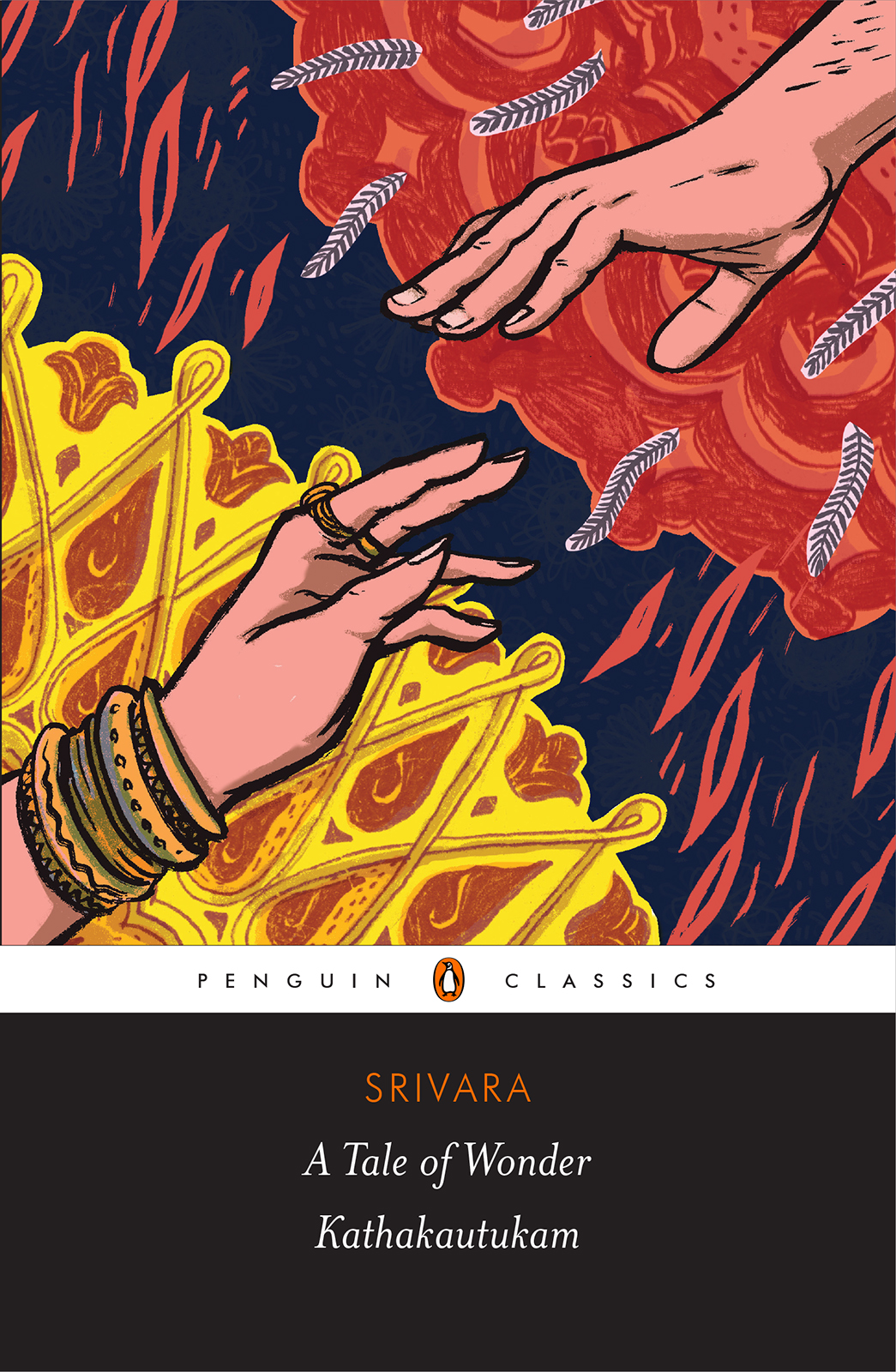

Srivara was a significant Sanskrit scholar and poet who was active in Kashmir in the fifteenth century. His best-known work is the third Rajatarangini, a sequel to the famous history of Kashmir which was commenced with the same name by Kalhana 300 years earlier and continued by Jonaraja. His present work had, however, become obscure and its manuscript was found there only in the nineteenth century. It is inspired by a celebrated poem in Persian, and in it he has also mentioned his proficiency in that language.

Aditya Narayan Dhairyasheel Haksar is a well-known translator of Sanskrit classics. For many years a career diplomat, he served at the United Nations and as the Indian high commissioner and ambassador in various countries. His translations from the Sanskrit include those of several great works by ancient poets like Bhasa and Kalidasa, Bhartrihari and Dandin, Kshemendra and Kalyana Malla, all published as Penguin Classics. He has also compiled A Treasury of Sanskrit Poetry, which was recently translated into Arabic in the UAE.

P.M.S.

Introduction

Here presented is a translation of the little-known Sanskrit verse epic Kathakautukam, written by the poet-scholar Srivara in fifteenth-century Kashmir. In modern times, its text was located there during the late nineteenth century and then edited and published in Bombay in 1901. and possibly some unpublished research, it has remained unnoticed and perhaps never been translated so far. The present work is intended to fill the gap and bring out this fascinating poem from past oblivion for general readership today.

This epic poetry from Kashmir, here titled A Tale of Wonder, deserves more exposure in the present times. Apart from its literary quality, and the need to make such forgotten works available in the mainstream of modern reading, there are also some other worthwhile considerations. These include a background of historical change and cultural intermingling reflected in its composition and theme, comparatively unusual in Sanskrit literature, and the manner of its presentation. These aspects are also reminders of a little-remembered chapter of national history. As such, some words on them may be a suitable prelude to this introduction.

To begin with, this poetic account provides a fine example of the cultural confluence not often noticed in Sanskrit literature. Written with sophistication in the classical style of that ancient language, it begins with the acknowledgement of its origin from a yavana source, which is clearly Persian in this context. Secondly, the cultural mingling in it is not limited to narrative details but is also drawn from theology, mythology and mystic philosophy. Finally, the contents are derived both from existing Indian concepts and those later acquired from external sources. They also include specific information about the works dating, some details of its author and his mentor and of the then reigning ruler and conditions of Kashmir.

We may start with a brief historical background to Kathakautukam. As outlined in its first chapter, it is derived from the Persian masnavi, or poem, Yusuf wa Zuleikha, or Yusuf and Zuleikha, written by Mulla Jami from Herat. This was Maulana Nuruddin Abdul Rahman Jami (141492), a well-known savant of the time, also named in the Bombay publication mentioned under note 1 on p. ix. His classic poem was first translated into English in 1882 by the British scholar R.T.H. Griffith, In Griffiths words, this work, a romantic tale of the love, the sufferings, and the crowning happiness of Zuleikha [...] was intended to shadow forth the human souls love for the highest beauty and goodnessa love which attains fruit only after the soul has passed through the hardest travails.

Recalculated in accordance with the modern calendar, the local dating information in Kathakautukam (1.3739) would show that Jamis tale was perhaps written in 1451. Its Sanskrit retelling appears to have been done a little later in the same century by Pandit Srivara, a disciple of Pandit Jonaraja. Both are better known as fifteenth-century scholars who wrote the first and second sequels to Rajatarangini, the history of Kashmir in Sanskrit commenced by Kalhana in the twelfth century. Three hundred years later, the contemporary king of Kashmir, praised and described in Kathakautukam, is Muhammad Shah (148486). He was the third in line from the celebrated Zainul Abedin (142070), the royal patron of Jonaraja, whose long reign ushered in an era of stability, prosperity and cultural interaction in Kashmir, which are also mentioned by Srivara.

The cultural interaction is also reflected in the sequels to Kalhanas history, the second and third Rajataranginis by Jonaraja and Srivara, and the later ones by Prajyabhatta and Suka. All have been subjects of further academic research today. The present translation could hopefully be another step in the same direction.

Kathakautukam was described by the Austrian scholar and historian of Sanskrit M. Winternitz as an adaptation rather than translation of Jamis poem. In his words it is an amalgamation of the Hebrew story, Persian romantic ballad and the Indian Siva cult. In this description he omitted mention of another important contributory source, namely, Islam. Apart from prayers to the god Shiva in its prologue and epilogue, this Sanskrit epic also contains an opening invocation to the holy Prophet Muhammad, who is addressed in it as paigambar shiromani, or the crown jewel of prophets, to whom its story was revealed by a divine messenger. Separately, the work also mentions the prophets assembled in paradise, and the subsequent creation of Adam, the progenitor of the human race, as recounted in Hebrew, Christian and Islamic scriptures. In his poem Srivara has also listed some prominent descendants of Adam in the line that preceded Yusuf.

The story of the prophet Yusuf is recounted in Surah XII (2332, 51) of the Holy Quran. He also features with the name Joseph in the Holy Bible, Old Testament, Book of Genesis (35, 37, 3950). Both cover the boy Yusufs abandonment, his sale as a slave in Egypt and his encounter there with his masters lustful wife, who is not named in either scripture. Neither do they make any mention of Zuleikha, though the divine aspect of Yusuf seems clear. But she is very much there in Jamis Persian poem from where she comes to Kathakautukam. In both these works she is part of a parable of the soul in search of god.

It would seem that Zuleikha is the more active figure in the works of both Jami and Srivara. It is she who longs for Yusuf and repeatedly suffers in her attempts to attain him. This mystic undertone of the soul seeking god appears fully in the poem of Jami, and is also clear in

CLASSICS

CLASSICS