Table of Contents

BOLLINGEN SERIES

IBN KHALDN

THE MUQADDIMAH

An Introduction to History

TRANSLATED AND INTRODUCED BY

FRANZ ROSENTHAL

ABRIDGED AND EDITED BY

N. J. DAWOOD

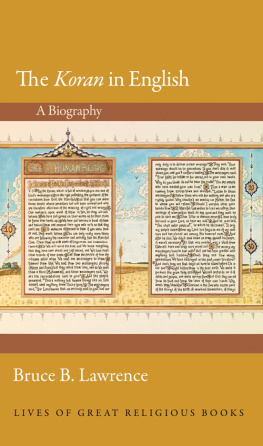

With a new introduction by Bruce B. Lawrence

BOLLINGEN SERIES

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Abridged edition 1967, 2005 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

All Rights Reserved

First edition, 1967

First Princeton/Bollingen Paperback printing, 1969

New introduction by Bruce B. Lawrence, 2005

First Princeton Classics edition, 2015

This is an abridgment of the three-volume edition translated, and with an introduction, by Franz Rosenthal, published by Pantheon Books as Bollingen Series XLIII and copyright 1958 by Bollingen Foundation, Inc., New York, NY. A second edition, with corrections and augmented bibliography, was published by Princeton University Press in 1967. In the present edition, the notes to the main text are Professor Rosenthals unless otherwise noted.

The abridged edtion was originally published in 1967 jointly by

Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. and Martin Secker and Warburg Ltd., London.

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-691-16628-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015930405

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

press.princeton.edu

eISBN: 978-1-400-86609-0

R0

Contents

vii

xxvii

INTRODUCTION BY N. J. DAWOOD xxxvii

INTRODUCTION TO THE 2005 EDITION

by Bruce B. Lawrence

This is the abridged version of the only complete English translation of the Muqaddimah (introduction), which was published in 1958 in three volumes for the Bollingen Foundation. The Muqaddimah is the most significant, and challenging, Islamic history of the premodern world. Its author was the fourteenth-century Mediterranean scholar Ibn Khaldn (13321406).

Ibn Khaldn was a man of his time, but he was not like others of his time. He was marked by travel, even before he was born. In the eighth century his ancestors emigrated from Southern Arabia, or Yemen, to Andalusia, or southern Spain, then a part of the Muslim world. His full name attests to his Yemeni roots: Abd-ar-Ramn Ab Zayd ibn Muammad ibn Muammad ibn Khaldn al-aram. Al-aram links its bearer to Hadramut, a part of Yemen. Other privileged members of Andalusian society were also Arab immigrants, though many, including Ibn Khaldns forbears, had intermarried with indigenous Berbers. What distinguished Ibn Khaldn was neither his Arab lineage nor his linkage to Berbers via marriage but his Mediterranean location. At the intersection of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim influences, heir to Greek science and Arabic poetry, and connected by trade and history to Asia, the Mediterranean Sea had become the nexus of Muslim cosmopolitanism by the fourteenth century. Social mobility as well as physical travel animated Mediterranean Muslims, especially those, like Ibn Khaldn, who rose to high posts in government, law, and education. Travel ( rilah ) became the model for his autobiography, At-Tarf bi-Ibn Khaldn wa-rihlatuhu gharban wa-sharqan, or Biography of Ibn Khaldn and His Travel in the West and in the East (hereafter referred to as Autobiography) . his is unusual because he attempts to place his own life squarely at the intersection of East and West. Begun in the last decade of his life and continuing up through his meeting with Tamerlane (in 1401), it situates him in the midst of the political activities of his time, but even more, it stresses how crucial is the awareness of geographical/ historical factors in assessing political events and their consequences.

What made Ibn Khaldn different was not travel per se but rather his ability to travel in the imagination of his own world, to create another perspective that at once linked him to his contemporaries yet set him apart from them. Whether we call this disposition quirkiness or eccentricity, narcissism or genius,

Marking himself as different was almost reflexive for Ibn Khaldn. He was different not just in his thought and speech but also in his dress. When he served as a judge in Cairo, he continued to wear Maghribi (or North African) robes instead of the lighter robes of Egyptian judges. Though he may have been uncomfortable, he was indicating pride in his Andalusian roots, without, however, suggesting that he was less than a faithful, observant Muslim or other than an obedient, subservient officer of the Egyptian state.

In his writing Ibn Khaldn also expressed difference, but always within limits and often by inference. It must be remembered that he was not employed to be a historian. He was a juridical activist with a secondary interest in history. Particularly in the odd circumstances of his own life experience did he hope to find lessons ( ibar ) that would be instructive for others. While his Autobiography ranges over many moments, none is more poignant, or more instructive, than his meetings with Tamerlane. The year was 1401. The place was Damascus. Tamerlane had just laid siege to the Mamluk city, which had not yet surrendered. During the previous twenty years Tamerlane had become the most feared and successful warrior from the East after the Mongol chieftain Chingiz Khan. Tamerlane was heir to Chingiz Khan in a double sense. Though Turkish and Muslim, he also had Mongol lineage, with shamanic loyalties, through his mother. Even more important, Tamerlane had inherited the Mongol ideal of universal sovereignty via military conquest. He had been systematic in his plundering and massacres, from Moscow in the north to Delhi in the south to Izmir in the west. No one was spared: all those conquered, whether Muslim or not, were treated as prisoners. Some were tortured, many were slain, all were at risk.

When Ibn Khaldn was summoned by Tamerlane in January 1401, he met him outside Damascus, where the conqueror had camped while his army laid siege to the city. Ibn Khaldn feared for his life. Yet he also knew from reports that Tamerlane could be indulgent as well as cruel, and that he had befriended scholars and mystics on previous occasions. Ibn Khaldn won Tamerlanes confidence, so much so that the account of their meetings justified his supplementary labor as a historian. Not only did Ibn Khaldn claim a role in gaining pardon for Mamluk prisoners of Tamerlane, but he also saw in the Central Asian world conqueror a Turco-Mongol vindication of his own thesis, to wit, that civilization is always and everywhere marked by the fundamental difference between urban and primitive, producing a tension that is also an interplay between nomad and merchant, desert and city, orality and literacy. Ibn Khaldn may have been projecting his own lifes ambition in the subsequent portrait he provided of Timur, or Tamerlane:

This king Timur is one of the greatest and mightiest of kings. Some attribute to him knowledge, others attribute to him heresy because they note his preference for members of the House (of Ali), still others attribute to him the employment of magic and sorcery, but in all this there is nothing; it is simply that he is highly intelligent and perspicacious, addicted to debate and argumentation about what he knows and also about what he does not know.

The final part of this description could have served as an epitaph for Ibn Khaldn, even without the legacy of his Muqaddimah: he is highly intelligent and perspicacious, addicted to debate and argumentation about what he knows and also about what he does not know. It is his ability to test the limits of what is known and knowable that makes Ibn Khaldn an explorer of the mind and not a conventional intellectual in the terms of either his own time or later times in the history of Muslim civilization.