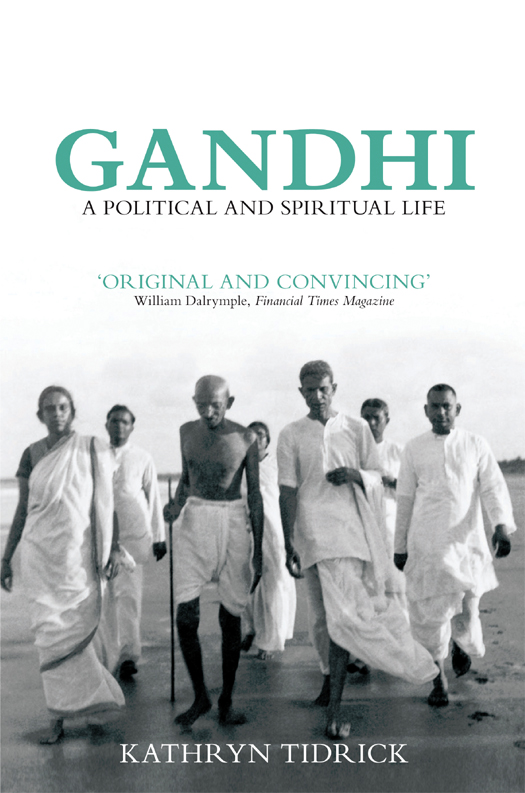

KATHRYN TIDRICK is the author of the highly regarded Heart Beguiling Araby: The English Romance with Arabia and Empire and the English Character.

This paperback edition first published by Verso 2013

First published by I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd 2006

Kathryn Tidrick 2006, 2013

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

eISBN: 978-1-78168-239-5

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

Contents

List of Illustrations

Student in London, 1888

Lawyer and emergent political leader, South Africa, about 1906

With Kasturbai shortly after returning to India in 1915

After being released from prison, spring 1924

Salt March, 1930, approaching Dandi

Arriving in England for the Round Table conference, 12 September 1931

With textile workers on a visit to Lancashire, 26 September 1931

Conferring with Nehru, July 1946

All illustrations courtesy of Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the friends and acquaintances in India who took an interest in my work, talked to me about Gandhi, and in various ways smoothed my path.

I would also like to thank the following institutions for their courteous assistance: the Gandhi Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi; the Gandhi Library, Sabarmati Ashram, Ahmedabad; the Navajivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad; the Gujarat Vidyapith, Ahmedabad; the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi; the National Archives of India, New Delhi; the India International Centre Library, New Delhi; the British Library; the Library of the Vegetarian Society, Altrincham, Cheshire; the Library of the Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Foundation, Washington, DC; the Library of the American University, Washington, DC; the Center for Research Libraries, Chicago. In addition, I take with pleasure the opportunity presented by the publication of this book to record my indebtedness to the Library of Congress, which over the years in connection with this and other projects has been my principal resource. Its staffs dedication is beyond praise.

Lead, Kindly Light, amid the encircling gloom,

Lead thou me on;

The night is dark, and I am far from home,

Lead thou me on.

Keep thou my feet; I do not ask to see

The distant scene; one step enough for me.

To Rachel and Sabino

Prologue

T his is the story of the greatest Indian godman of them all. Known to the world as the leader of the Indian nationalist movement, Mohandas Gandhi entered politics, not to liberate his country in the sense understood by other Indian leaders and the western public which followed his career with such fascinated attention, but to establish the Kingdom of Heaven on earth. The Indian masses, who revered him, grasped this, up to a point. They knew that a mahatma walked among them, poured out their devotion, and awaited results. But the adoring masses possessed as little conception as anyone else outside Gandhis inner circle of the complex system of religious ideas, refined through years of self-scrutiny and reflection on events, which guided his every action. These ideas, though clothed in Hindu terminology, were not Hindu in origin. They owed their existence to Gandhis precipitation in his youth into the atmosphere of experimentation with esoteric and occult forms of religion which flourished in the London of the 1880s, where he went to qualify as a barrister. An innocent vegetarian, seeking out first wholesome food and then the company of reformers who ate through preference what he ate through obedience to custom, the young Gandhi stumbled into a world of theosophists, esoteric Christians, vital food enthusiasts, and exponents of the simple life, which proved utterly formative. Later influences Tolstoy, Ruskin, the American New Thought movement which spawned Christian Science and other forms of positive thinking were absorbed into a system of belief whose essential features were already in place.

The principal article of this belief system has to be stated as clearly as possible at the outset. It was that he, Gandhi, was the pre-ordained and potentially divine world saviour whose coming was logically implicit in the ancient, and especially Eastern, religious writings to which so many of his English acquaintances had turned in their search for a new revelation of Gods purpose in the world.

How this came about will be related at length later on. It need only be said here that it was not a process which took place overnight. The awkward and barely educated young man who flitted like a ghost through the furnished rooms and lecture halls of late-Victorian London had much to learn, about his own as well as other religions, before he could begin to entertain such thoughts about himself. The process of learning began during the three years he spent in London. It continued during the two years he spent in India trying unsuccessfully to practise law, and it came to its extraordinary fruition in South Africa in 1893 or 1894.

From then on, events as a rule conspired to confirm in Gandhi the suspicion awakened in him by his reading and deliberations that it was his destiny to lead a troubled world along the path to salvation.

When he first began to apply his new idea of himself to the practical business of life and politics (his experiments with Truth) the results perhaps at first exceeded his expectations. But after a while they simply confirmed him in the kind of expectations he should have. He had an aptitude for politics which was evident from the start, and he employed it then and later in the service of his larger aims. His rise to prominence in South African Indian politics was rapid, and his consolidation of his position remarkable. When he returned to India in 1915, it was because he believed that the next act of the drama must unfold on an Indian stage. He would set the world to rights by setting India right first.

The career that followed was by any standard an amazing one. Within five years of his return Gandhi had captured the Indian National Congress and got it into a position of beholdment to him from which it was never, before 1947, completely to shake itself free. His power over the masses, his genuine if equivocal standing with the British, his usefulness as a conciliator and focus of unity, his worldwide reputation as an elevated personality, all worked together to bring about his long ascendancy in Indian politics. Taking care not to tie himself down to a mere official position within the Congress, Gandhi used it as his instrument, and seemed to come and go from it mostly as he pleased. At times he took an astonishingly long view, and was prepared to detach himself for years if necessary from its public activities, while he waited for conditions once again to become ripe for his intervention. These waiting games were not always played serenely. Though Gandhi strove for detachment he did not always achieve it. Sometimes the dark nights of the soul were so long that he felt doubtful whether his ends would ever, after all, be accomplished, and at such times he consoled himself with the expectation of reincarnation. Might it not be that God would require from him one more lifetime of celibacy and suffering before he was pure enough to shine forth as the invincible instrument of his will? These preoccupations did not reside in some mental compartment which can be labelled Gandhis religious ideas. They had a profound and practical influence on his political career.

![Gandhi - Gandhi: [the true man behind modern India]](/uploads/posts/book/175484/thumbs/gandhi-gandhi-the-true-man-behind-modern-india.jpg)