DANIEL KOLAK, SERIES EDITOR

Arthur Schopenhauer

The World as Will and Presentation

Volume One

TRANSLATED BY

RICHARD E. AQUILA

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE

IN COLLABORATION WITH

DAVID CARUS

First published 2008 by Pearson Education, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2008 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

ISBN-13: 9780321355782 (pbk)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

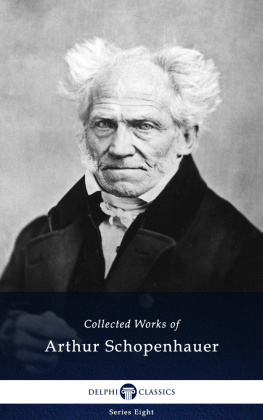

Schopenhauer, Arthur, 1788-1860.

[Welt als Wille und Vorstellung. English]

Arthur Schopenhauer: the world as will and presentation / translated

by

Richard E. Aquila in collaboration with David Carus.

p. cm. (Longman library of primary sources in philosophy)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-321-35578-4 (alk. paper)

1. Philosophy. 2. Will. 3. Idea (Philosophy) 4. Knowledge, Theory of.

I. Title.

B3138.E5A65 2008

193-dc 22

Library of Congress Control Number: 2007001262

Contents

FOR MY GRANDCHILDREN

Megan

Sam

Emilio

Preface to the

Translation

German editors of Schopenhauers works are confronted with a well known curse that the author laid upon everyone who in future printings of my work will modify anything of them knowingly, be it a sentence or just one word, a syllable, a letter, a punctuation mark. The reason for this lies in the fact that concepts often do not correspond with each other in different languages (so, writing this, I am aware that the concept of concept does not correspond exactly to the German Begriff, and neither does idea). Thus even the very best translation will at most be related to the original as the transposition of a given piece of music into another key is to the given piece itself; and as Schopenhauer adds, those who understand music know what that means.

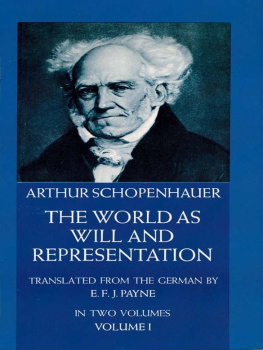

According to this estimation there are two ways to proceed, both of them unsatisfying: either a translation remains dead and its style is forced, stiff and unnatural or it becomes free, in other words, is content with an peu prs and thus is incorrect. Up to now, a translation of Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung has been available to Anglo-American scholars that comes nearer to the first alternative. Even to one who, like me, has no great competence in English, it is obvious that the translation of Eric F. J. Payne, The World as Will and Representation, sounds like a German text written in English words. This might be an advantage for German readers but not to those to whom it is addressed. So much the more it is therefore to be applauded that a translation is here presented with a main aim of providing a readable English text. Such a new translation is not only able to draw more attention to one of the most important European thinkers for the Anglo-American sphere all the more appropriate inasmuch as Schopenhauers philosophy was first discovered and acknowledged in England 153 years ago, even before he became known in his homeland. It also contributes to a better understanding of Schopenhauers philosophy by English readers. Any translation that is truly readable, and yet as accurate as a translation could be, is necessarily the product of the effort to find a path between the Scylla of an artificial, inanimate style and the Charybdis of free transposition. From some discussions with the translators in which I have marginally participated, I know how much care has been put into the best translation of some of the main concepts, as well as in regard to the meaning of the words in their use in common English. One may get an impression of these discussions from the translators introduction.

It is always a difficult task to minimize the general disadvantages of translations, with their necessary give and take, not to mention the danger of mixing translation with interpretation, which is particularly high in the case of Schopenhauers philosophy, because it is more in need of interpretation than some others. As to how far the present translation succeeds in this task has to be judged by the experts. In any case I am very glad about this new translation, and I admire the courage and the work of Richard Aquila and David Cams. The translations of Eric F. J. Payne have been most important for the development of Anglo-American Schopenhauer research. They have undeniable merits, and Payne has rightly been named an honorary president of the Schopenhauer Society. But now-as indicated by an increasing number of remarks from many sides in the last years the time has come for this new translation, which I welcome in the name of the international Schopenhauer Society. I am sure that it will contribute to a new era of occupation with Schopenhauers philosophy, not only in the Anglo-American world, but no less in India, where Schopenhauer has recently been discovered, and indeed all over the world.

MATTHIAS KOSSLER

University of Mainz

President, Schopenhauer-Gesellschaft

__________________________________________

Notes

Der handschriftliche Nachlass, ed. Arthur Hbscher (Frankfurt: W. Kramer, 19661975), IV/2, p. 33.

Parerga und Paralipomena, vol. II, Smtliche Werke, ed. Arthur Hbscher, vol. 6, p. 602.

Translators

Introduction

In 1819 Arthur Schopenhauer (17881860) published his chief work, Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung. In 1844, rather than subject the original to a major revision, he supplemented it with a second volume:

for the reason that the twenty-five years that have passed have brought such a notable alteration in my manner of exposition and in the tone of delivery that it just would not do to fuse the content of the second volume into a whole with that of the firstI therefore put forth the two works in separation, and have often changed nothing in the earlier exposition even where I would now express myself quite differently; for I wanted to guard against spoiling the work of my younger years with the carping of old age.

The two-volume work then appeared in a third edition in 1859. The present is a translation of the first volume of that edition. It has been produced in collaboration with David Cams, whose translation of the second volume reflects a reciprocal division of labor.

The world is a presentation to me. In this sentence, the first of the book, Schopenhauer characterizes one of the two sides of die Welt, the world, as he sees it. If there is such a thing as literal translation, the present is, at least in one respect, decidedly non-literal. Why not:

Next page