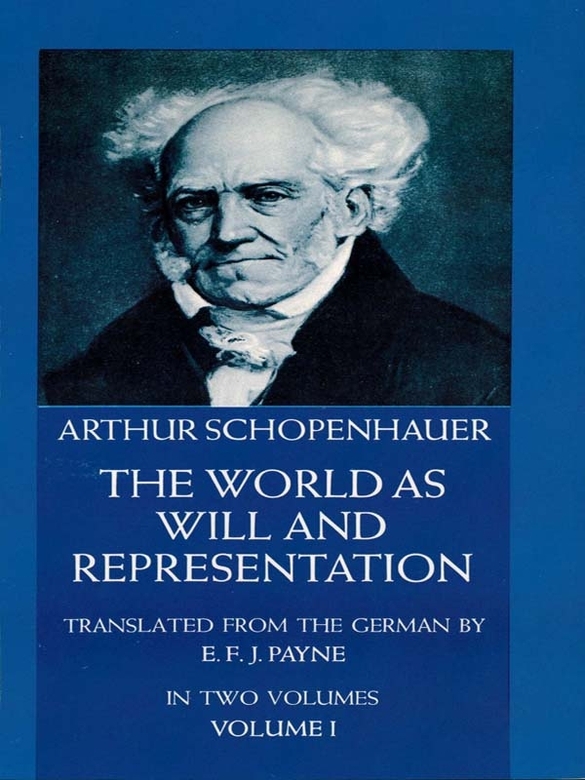

Arthur Schopenhauer - The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1

Here you can read online Arthur Schopenhauer - The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: Dover Publications, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1

- Author:

- Publisher:Dover Publications

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Volume 1 of the definitive English translation of one of the most important philosophical works of the 19th century, the basic statement in one important stream of post-Kantian thought. Corrects nearly 1,000 errors and omissions in the older Haldane-Kemp translation. For the first time, this edition translates and locates all quotes and provides full index.

Arthur Schopenhauer: author's other books

Who wrote The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Cest le privilge du vrai gnie, et surtout du gnie qui ouvre une carrire, de faire impunment de grandes fautes.

Voltaire [ Sicle de Louis XIV, ch. 32]

[It is the privilege of true genius, and especially of the genius who opens up a new path, to make great mistakes with impunity. Tr.]

I t is much easier to point out the faults and errors in the work of a great mind than to give a clear and complete exposition of its value. For the faults are something particular and finite, which can therefore be taken in fully at a glance. On the other hand, the very stamp that genius impresses on its works is that their excellence is unfathomable and inexhaustible, and therefore they do not become obsolete, but are the instructors of many succeeding centuries. The perfected masterpiece of a truly great mind will always have a profound and vigorous effect on the whole human race, so much so that it is impossible to calculate to what distant centuries and countries its enlightening influence may reach. This is always the case, since, however accomplished and rich the age might be in which the masterpiece itself arose, genius always rises like a palm-tree above the soil in which it is rooted.

A far-reaching, deep, and widespread effect of this kind cannot, however, take place suddenly, on account of the great difference between the genius and ordinary mankind. The knowledge this one man in a lifetime drew directly from life and the world, won, and presented to others as acquired and finished, cannot at once become the property of mankind, since men have not so much strength to receive as the genius has to give. But even after a successful struggle with unworthy opponents, who contest the life of what is immortal at its very birth, and would like to nip in the bud the salvation of mankind (like the serpent in Hercules cradle), that knowledge must first wander through the circuitous paths of innumerable false interpretations and distorted applications; it must overcome the attempts to unite it with old errors, and thus live in conflict, until a new and unprejudiced generation grows up to meet it. Even in youth this generation gradually receives some of the contents of that source from a thousand different channels, assimilates it by degrees, and thus shares in the benefit that was to flow from that great mind to mankind. So slow is the advance in the education of the human race, that feeble, and at the same time refractory, pupil of genius. Thus the whole strength and importance of Kants teaching will become evident only in the course of time, when the spirit of the age, itself gradually reformed and altered in the most important and essential respect by the influence of that teaching, furnishes living evidence of the power of that giant mind. However, I will certainly not take upon myself the thankless role of Calchas and Cassandra by presumptuously anticipating the spirit of the age. Only I may be allowed, in agreement with what has been said, to regard Kants works as still very new, whereas many at the present day look upon them as already antiquated. Indeed, they have discarded them as settled and done with, or, as they put it, have left them behind. Others, emboldened by this, ignore them altogether, and with brazen effrontery continue to philosophize about God and the soul on the assumptions of the old realistic dogmatism and its scholastic philosophy. This is as if we wished to introduce into modern chemistry the theories of the alchemists. Kants works, however, do not need my feeble eulogy, but will themselves externally extol their master, and will always live on earth, though perhaps not in the letter, yet in the spirit.

But, of course, if we look back at the first result of his doctrines, and the efforts and events in the sphere of philosophy during the period that has since elapsed, we see the corroboration of a very depressing saying of Goethe: Just as the water displaced by a ship immediately flows in again behind it, so, when eminent minds have pushed error on one side and made room for themselves, it naturally closes in behind them again very rapidly. ( Poetry and Truth , Pt. 3, [Book 15], p. 521.) This period, however, has been only an episode that is to be reckoned as part of the above-mentioned fate of all new and great knowledge, an episode now unmistakably near its end, since the bubble so steadily blown out is at last bursting. People generally are beginning to be conscious that real and serious philosophy still stands where Kant left it. In any case, I cannot see that anything has been done in philosophy between him and me; I therefore take my departure direct from him.

What I have in view in this Appendix to my work is really only a vindication of the teaching I have set forth in it, in so far as in many points it does not agree with the Kantian philosophy, but actually contradicts it. Yet a discussion thereof is necessary, for evidently my line of thought, different as its content is from the Kantian, is completely under its influence, and necessarily presupposes and starts from it; and I confess that, next to the impression of the world of perception, I owe what is best in my own development to the impression made by Kants works, the sacred writings of the Hindus, and Plato. But I can justify the disagreements with Kant that are nevertheless to be found in my work, only by accusing him of error in the same points, and exposing mistakes he made. In this Appendix I must therefore deal with Kant in a thoroughly polemical manner, and seriously and with every effort; for only thus can the error that clings to Kants teaching be burnished away, and the truth of that teaching shine all the more brightly, and endure more positively. Therefore it must not be expected that my sincere and deep reverence for Kant will also extend to his weaknesses and mistakes, and hence that I should expose them only with the most cautious indulgence, for thus my language would of necessity become feeble and flat through circumlocutions. Towards a living person such indulgence is needed, since human frailty cannot endure even the most just refutation of an error, unless it is tempered by soothing and flattery, and hardly even then; and a teacher of the ages and benefactor of mankind deserves at least that his human frailty shall also be treated with indulgence, so that he may not be caused any pain. But the man who is dead has cast this weakness aside; his merit stands firm; time will purify it more and more of all overestimation and detraction. His mistakes must be separated from it, rendered harmless, and then given over to oblivion. Therefore in the polemic I am about to institute against Kant, I have only his mistakes and weaknesses in view. I face them with hostility, and wage a relentless war of extermination upon them, always mindful not to conceal them with indulgence, but rather to place them in the brightest light, the more surely to reduce them to nought. For the reasons above-mentioned, I am not aware here of either injustice or ingratitude to Kant. But in order that, even in the eyes of others, every appearance of malignancy may be removed, I will first of all bring out clearly my deeply-felt veneration for and gratitude to Kant by stating briefly what in my eyes appears to be his principal merit. I will do this from so general a standpoint that it will not be necessary for me to touch on those points in which I must later contradict him.

Kants greatest merit is the distinction of the phenomenon from the thing-in-itself , based on the proof that between things and us there always stands the intellect , and that on this account they cannot be known according to what they may be in themselves. He was led on to this path by Locke (see Prolegomena to every Metaphysic , 13, note 2). Locke had shown that the secondary qualities of things, such as sound, odour, colour, hardness, softness, smoothness, and the like, founded on the affections of the senses, do not belong to the objective body, the thing-in-itself. To this, on the contrary, he attributed only the primary qualities, i.e., those that presuppose merely space and impenetrability, and so extension, shape, solidity, number, mobility. But this Lockean distinction, which was easy to find, and keeps only to the surface of things, was, so to speak, merely a youthful prelude to the Kantian. Thus, starting from an incomparably higher standpoint, Kant explains all that Locke had admitted as qualitates primariae , that is, as qualities of the thing-in-itself, as also belonging merely to its phenomenon in our faculty of perception or apprehension, and this just because the conditions of this faculty, namely space, time, and causality, are known by us a priori . Thus Locke had abstracted from the thing-in-itself the share that the sense-organs have in its phenomenon; but Kant further abstracted the share of the brain-functions (although not under this name). In this way the distinction between the phenomenon and the thing-in-itself obtained an infinitely greater significance, and a very much deeper meaning. For this purpose he had to take in hand the great separation of our a priori from our a posteriori knowledge, which before him had never been made with proper precision and completeness or with clear and conscious knowledge. Accordingly, this then became the principal subject of his profound investigations. We wish here to observe at once that Kants philosophy has a three-fold relation to that of his predecessors; firstly, as we have seen, a relation to Lockes philosophy, confirming and extending it; secondly, a relation to Humes, correcting and employing it, a relation that we find most distinctly expressed in the preface to the Prolegomena (that finest and most comprehensible of all Kants principal works, which is far too little read, for it immensely facilitates the study of his philosophy); thirdly, a decidedly polemical and destructive relation to the philosophy of Leibniz and Wolff. We should know all three doctrines before proceeding to the study of the Kantian philosophy. Now if, in accordance with the above, the distinction of the phenomenon from the thing-in-itself, and hence the doctrine of the complete diversity of the ideal from the real, is the fundamental characteristic of the Kantian philosophy, then the assertion of the absolute identity of these two, which appeared soon afterwards, affords a melancholy proof of the saying of Goethe previously quoted. This is all the more the case, inasmuch as that identity rested on nothing but the vapouring of intellectual intuition. Accordingly, it was only a return to the crudeness of the common view, masked under the imposing impression of an air of importance, under bombast and nonsense. It became the worthy starting-point of the even grosser nonsense of the ponderous and witless Hegel. Now as Kants separation of the phenomenon from the thing-in-itself, arrived at in the manner previously explained, far surpassed in the profundity and thoughtfulness of its argument all that had ever existed, it was infinitely important in its results. For in it he propounded, quite originally and in an entirely new way, the same truth, found from a new aspect and on a new path, which Plato untiringly repeats, and generally expresses in his language as follows. This world that appears to the senses has no true being, but only a ceaseless becoming; it is, and it also is not; and its comprehension is not so much a knowledge as an illusion. This is what he expresses in a myth at the beginning of the seventh book of the Republic , the most important passage in all his works, which has been mentioned already in the third book of the present work. He says that men, firmly chained in a dark cave, see neither the genuine original light nor actual things, but only the inadequate light of the fire in the cave, and the shadows of actual things passing by the fire behind their backs. Yet they imagine that the shadows are the reality, and that determining the succession of these shadows is true wisdom. The same truth, though presented quite differently, is also a principal teaching of the Vedas and Puranas, namely the doctrine of Maya, by which is understood nothing but what Kant calls the phenomenon as opposed to the thing-in-itself. For the work of Maya is stated to be precisely this visible world in which we are, a magic effect called into being, an unstable and inconstant illusion without substance, comparable to the optical illusion and the dream, a veil enveloping human consciousness, a something of which it is equally false and equally true to say that it is and that it is not. Now Kant not only expressed the same doctrine in an entirely new and original way, but made of it a proved and incontestable truth through the most calm and dispassionate presentation. Plato and the Indians, on the other hand, had based their contentions merely on a universal perception of the world; they produced them as the direct utterance of their consciousness, and presented them mythically and poetically rather than philosophically and distinctly. In this respect they are related to Kant as are the Pythagoreans Hicetas, Philolaus, and Aristarchus, who asserted the motion of the earth round the stationary sun, to Copernicus. Such clear knowledge and calm, deliberate presentation of this dreamlike quality of the whole world is really the basis of the whole Kantian philosophy; it is its soul and its greatest merit. He achieved it by taking to pieces the whole machinery of our cognitive faculty, by means of which the phantasmagoria of the objective world is brought about, and presenting it piecemeal with marvellous insight and ability. All previous Western philosophy, appearing unspeakably clumsy when compared with the Kantian, had failed to recognize that truth, and had therefore in reality always spoken as if in a dream. Kant first suddenly wakened it from this dream; therefore the last sleepers (Mendelssohn) called him the all-pulverizer. He showed that the laws which rule with inviolable necessity in existence, i.e., in experience generally, are not to be applied to deduce and explain existence itself; that their validity is therefore only relative, in other words, begins only after existence, the world of experience generally, is already settled and established; that in consequence these laws cannot be our guiding line when we come to the explanation of the existence of the world and of ourselves. All previous Western philosophers had imagined that these laws, according to which all phenomena are connected to one another, and all of whichtime and space as well as causality and inferenceI comprehend under the expression the principle of sufficient reason, were absolute laws conditioned by nothing at all, aeternae veritates; that the world itself existed only in consequence of and in conformity with them; and that under their guidance the whole riddle of the world must therefore be capable of solution. The assumptions made for this purpose, which Kant criticizes under the name of the Ideas of reason ( Vernunft), really served only to raise the mere phenomenon, the work of Maya, the shadow-world of Plato, to the one highest reality, to put it in the place of the innermost and true essence of things, and thus to render the real knowledge thereof impossible, in a word, to send the dreamers still more soundly to sleep. Kant showed that those laws, and consequently the world itself, are conditioned by the subjects manner of knowing. From this it followed that, however far one might investigate and infer under the guidance of these laws, in the principal matter, i.e., in knowledge of the inner nature of the world in itself and outside the representation, no step forward was made, but one moved merely like a squirrel in his wheel. We therefore compare all the dogmatists to people who imagine that, if only they go straight forward long enough, they will come to the end of the world; but Kant had then circumnavigated the globe, and had shown that, because it is round, we cannot get out of it by horizontal movement, but that by perpendicular movement it is perhaps not impossible to do so. It can also be said that Kants teaching gives the insight that the beginning and end of the world are to be sought not without us, but rather within.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1»

Look at similar books to The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.