Why Schopenhauer Today?

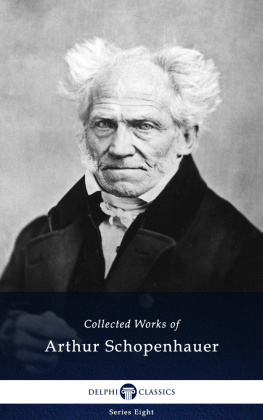

Arthur Schopenhauer (17881860) is currently one of the German philosophers of the nineteenth century who is liable to be skipped over in a survey of the philosophy of this period. In light of the less-canonical status of Schopenhauer today, its a surprising fact, as Fred Beiser has recently reminded us, that Arthur Schopenhauer was the most famous and influential philosopher in Germany from 1860 until the First World War. Indeed, Schopenhauer wielded considerable influence on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century philosophy, literature, psychology, and music , and parts of his philosophical system were important for figures as diverse as Sigmund Freud , Henri Bergson , Ludwig Wittgenstein , Iris Murdoch, Susanne Langer, Thomas Hardy, George Eliot , Olive Schreiner , Thomas Mann, Marcel Proust, Johannes Brahms, Richard Wagner , Gustav Mahler, and Arnold Schnberg. His philosophy even sparked an entire controversythe pessimism controversyamong some now lesser known figures in Germany, such as Eduard von Hartmann and Philipp Mainlnder, and was the driving influence on the early Nietzsche.

Some of Schopenhauers recent philosophical neglect could be due to the fact that he was also a popular and practical philosopher. This popularity was due to the wide readership of his Aphorismen zur Lebensweisheit ( Aphorisms of Worldly Wisdom ), a section of his late work, Parerga and Paralipomena, which became a kind of jaded handbook for the polite classes of fin de sicle Europe, offering them realistic guidance in achieving a tolerably happy lifein Schopenhauers words a eudaimonology.

Philosophers in research-oriented departments tend to eschew the popular and the practical (anything applied tends to be viewed with suspicion), so Schopenhauers popularityamong writers, artists, musicians, and ordinary educated folk in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuriesmay constitute a liability for more recent Anglo-American philosophers. While Schopenhauers thought continued to have influence in contemporary musical aesthetics , given his enormous influence on Romantic and Modernist composers, and studies of his thought in the German-speaking world have remained steady, it has only been with a fairly recent revival of interest in Nietzsche (who proclaimed Schopenhauer his educator) that there has been a revival of scholarly and philosophical interest in Schopenhauers philosophical system in the Anglo-American world.

Are we now in the midst of a Schopenhauer Renaissance? Several recent developments attest to this: First, and most importantly, there is a new Cambridge Edition of the Works of Schopenhauer (ed. Chris Janaway), which will for the first time afford uniform, first-rate English translations of all of Schopenhauers published writings. This high-quality edition promises to do for Anglo-American Schopenhauer scholarship what the Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant (eds. Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood) did for Anglo-American Kant scholarship. Second, Anglo-American Schopenhauer scholarship is increasing in quantity and quality. There have been several special issues of prestigious journals devoted to Schopenhauer in the last ten years: For example, the European Journal of Philosophy published a special issue on Schopenhauers philosophy of value edited by Christopher Janaway and Alex Neill in 2008; The Kantian Review published a special issue on Kant and Schopenhauer edited by Richard Aquila in 2012; and Enrahonar , which publishes in English, Spanish, and Catalan out of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, has published a special issue on Schopenhauer edited by Marta Tafalla in 2015. Also, two special Schopenhauer symposia are being planned in the British Journal for the History of Philosophy by Jonathan Head and Dennis Vanden Auweele in honor of the 200th anniversary of the World as Will and Representation.

The publication of edited collections of scholarly essays in English on Schopenhauers work has been picking up pace since the 1999 appearance of the Cambridge Companion to Schopenhauer edited by Christopher Janaway. In 2012, Bart Vandenabeele edited Blackwells A Companion to Schopenhauer , and a more specialized volume of essays on Schopenhauers dissertation The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason appeared in 2017, commemorating the works 200th anniversary, edited by Jonathan Head and Dennis Vanden Auweele. Now you have before you another collection of high-level, cutting-edge scholarship: the Palgrave Schopenhauer Handbook .

Attractions of Schopenhauers Thought

There is the matter of style. Schopenhauer is a pleasure to read: He is witty, personal, at times sardonic, urbane, and employs striking metaphors and vivid imagery. One of Schopenhauers early translators into English, T. Bailey Saunders sums it up nicely stating that the author endows his style with a freshness and vigour which would be difficult to match in the philosophical writing of any country, and impossible in that of Germany. Although rewarding, it is nonetheless difficult and even downright painful to get through Fichtes Wissenschaftslehre (the Science of Knowing ), Hegels Phenomenology of Spirit , and Schellings System of Transcendental Idealism , but its not too surprising that Richard and Cosima Wagner would entertain and edify themselves in the evening by reading Schopenhauers main work aloud to each other!

Yet, style without substance would not make Schopenhauer especially worthy of philosophical study today. Indeed, there are both historical and internal-philosophical attractions to his thought that make him a particularly exciting thinker to investigate. One historical attraction is that Schopenhauer produced the last true system of philosophy in Germany, comprising an epistemology , metaphysics, aesthetics , ethics , and philosophy of religion , but the exact nature and influence of this system are still not well understood. While it is clear that Schopenhauer was a key figure in the development of German philosophy in the nineteenth century and the most important link between Kant and Nietzsche, its not clear exactly how this narrative should be understood and how Schopenhauer fits into it. New scholarship in philosophy often highlights previously unnoticed lacuna in extant research, unsolved puzzles, and hitherto unasked questions. This is certainly the case with this volume, which constitutes a significant step in contemporary Schopenhauer scholarship by engaging, not just with Schopenhauers primary texts, but also with the most recent scholarly work on this philosopher.

The handbook starts off with David Cartwrights careful retracing of the early influences and education that informed Schopenhauers main work, and he provides a helpful chronology of Schopenhauers life and times as a whole in the front matter of this volume. Cartwrights chapter situates Schopenhauers system as a whole into the authors life and the intellectual climate of the times. Next, Wolfgang Mann provides us with a nuanced perspective on how much of a follower of Plato Schopenhauer really was in his chapter, How Platonic are Schopenhauers Platonic Ideas ? And Gnter Zller in his Schopenhauers System of Freedom presents a somewhat unfamiliar view of Schopenhauer: Rather than being classified as a hard-determinist, he interprets him as being firmly in the tradition of classical German philosophy, which aims to secure freedom in the face of the causal order of nature.

With respect to the influence of Schopenhauers system, a recent above-cited book by Fred Beiser traces the pessimism controversy that ensued from 1860 to 1900 in Germany, and several of the contributors to this handbook pick up this thread and trace hitherto neglected streams of influence from Schopenhauers thought. Diego Cubero in his chapter on Schopenhauer, Schenker, and the Will of Music argues for Schopenhauer as a truly pivotal figure in the history of music theory through his influence on Heinrich Schenker . Further, Marco Segala in his chapter Metaphysics and the Sciences in Schopenhauer details Schopenhauers complex philosophy of nature and offers a better understanding of the influence of it on the philosophy of science in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Pearl Brilmyers chapter Schopenhauer and British Literary Feminism unearths the reception and influence Schopenhauers thought had on British women writers of the Victorian era, and brings to light the role of George Eliot and a cadre of women translators and novelists in popularizing Schopenhauers thoughton their own termsin Great Britain. Joo Constncios chapter Nietzsche and Schopenhauer: On Nihilism and the Ascetic Will to Nothingness argues that not only was Schopenhauer a profound influence on the early Nietzscheas is well knownbut also that he remained the key influence on Nietzsche even in his mature writings such as On the Genealogy of Morality , a notion that has been widely dismissed by canonical Nietzsche scholars. Schopenhauers French reception is Arnaud Franoiss concern as he traces the hitherto understudied influence of Schopenhauer on figures such as Henri Bergson and reveals the waxing and waning of this influence in France along with the countrys turbulent relations with Prussia/Germany. Finally, the reception of Schopenhauer in the USA has been almost entirely unstudied. Christa Buschendorf fills this important gap in her Grappling With German Atheism and Pessimism : The Reception of Schopenhauer in the United States. In this chapter, she surveys Schopenhauers influence on the transcendentalists among other nineteenth-century American philosophers and intellectuals.