The paper on which the book is based was originally read at the first Congress of the International Association for the History of Psychoanalysis, held in Paris in May 1987, and was published in the first issue of the Revue Internationale d'Histoire de la Psychanalyse. The English version, which I have now completely rewritten and greatly expanded, first appeared in the International Review of Psycho-Analysis, 16 (1989), pp. 35-76, and was also read to the IPTAR in New York in November 1987.

I take this opportunity to extend my thanks to Pearl King who, at the time I began researching for this paper, was the Honorary Archivist of the British Psycho-Analytical Society; to M. Molnar of the Freud Museum in London; and to the Sigmund Freud Copyrights in Colchester for their assistance and for having given me permission to quote from the letters used in this book. To Andrew Paskauskas I owe more than one extremely useful quotation from The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones 1908-1939 (1993). I am also particularly grateful to the late Ilse Hellman and to Dr Josephine Stross for all their help.

I would also like to thank Jill Duncan, Executive Archivist of the British Psycho-Analytical Society; Adriana Poyser, to whom I owe a special debt of gratitude because of her patience and intelligence in editing the manuscript; and Klara and Eric King, for their skill and patience in the production process of the book.

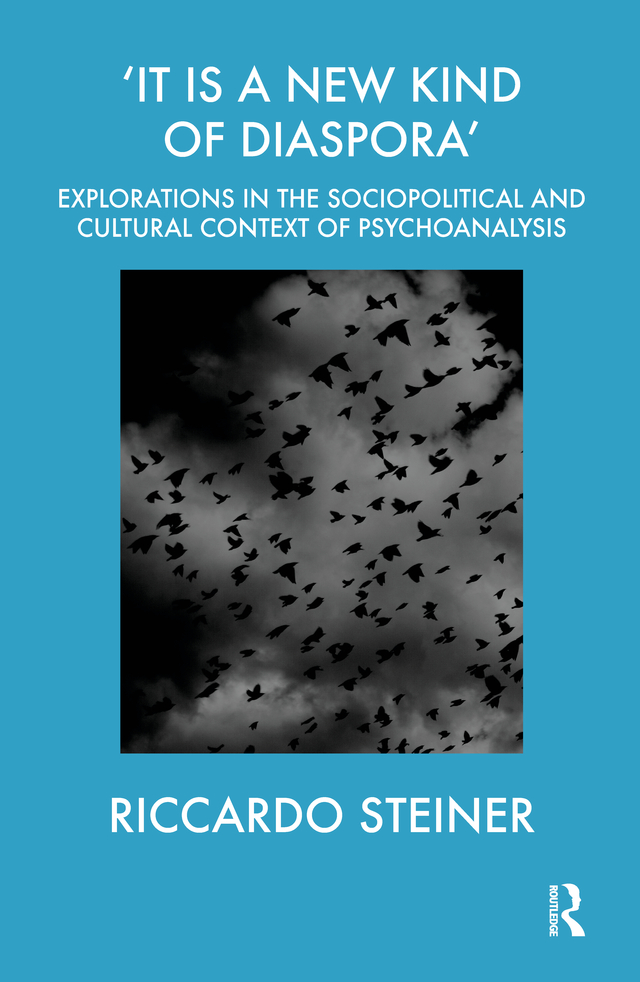

Cesare Sacerdoti wanted this book and made it possible for it to be published. He knows why I am particularly moved by his care. We both know what the Diaspora meant for us and our relatives.

Contents

Special "Kinder", special " Sorge"

Wilhelm Reich, Edith Jacobsohn, and political neutrality in psychoanalysis

Guide

As part of a broader research on the cultural effects of the "new diaspora" in Great Britain and in other countries as far as psychoanalysis is concerned, this book traces some aspects of the politics of emigration of German and Austrian psychoanalysts during the Nazi persecution.

Given the fundamental role played by Ernest Jones in that particular set of circumstances, and given that both Anna Freud and Ernest Jones were very interesting individuals, both in their intellectual and in their "institutional" stature (as one might call it, considering the role they played in the way psychoanalysis developed), it would seem to me that the Ernest Jones-Anna Freud correspondence during that period is an exceptionally important source for anyone who wishes to understand the significance of what I refer to in this book as "the politics of emigration".

The Ernest Jones-Anna Freud correspondence is an extensive exchange of letters, begun in the late 1920s and continued until Jones's death in 1958. Of these letters, about 220 were written between 1933 and 1939, concluding with a letter from Anna Freud to Jones dated 20 January 1939 and sent from her home at 20 Maresfield Gardens, London NW3, where she had found refuge, along with her father and family, a few months previously. In this same house, Freud was to die in September 1939, and it would remain Anna Freud's London home until her own death in 1982.

Space is limited here and leaves no room for lengthy methodological digressions. However, I need to remind the reader that this book cannot be other than a partial coming-to-terms with the issues under discussion. One of the major limitations is that I have been able to rely only on the material that is available in London. Using correspondence between Anna Freud and Ernest Jones, and that between Jones and A. Brill, Sigmund Freud, and others, as well as other documents, all deposited in the Archives of the British Psycho-Analytical Society, the book focuses mainly on the emigration of German and Austrian Jewish analysts to England, although the documents used allow the reader to get a very clear picture of the complex problems related to the same emigration to North America and other countries during the 1930s.

The correspondence held in the Archives of the British Psycho-Analytical Society is by no means complete. In fact, many of the lettersJones's as well as Anna Freud'sare missing, as are letters from other correspondents. It is more than probable that these and other material concerning the issues discussed here may be found among the numerous letters belonging to Anna Freud and others that, along with the originals of the letters Ernest Jones wrote to Anna Freud after 1945, have found their way to the Library of Congress, Washington, DC, and to other U.S. libraries. It is probable that additional data might well be uncovered by those who have access to these. However, without wanting to appear overly presumptuous, I am fairly confident that I have succeeded in providing a first, rough idea of the politics of emigration as they were conceived and put into practice in London in the years in question. I would not wish to cause any methodological perplexities, but I do not believe that the uncovering of other documents would seriously alter my reconstruction of events, at least as far as Jones is concerned. Having said this, there is no doubt that if new evidence were to be uncovered, it would help to complete the picture.

"It is a New Kind of Diaspora"

To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it "the way it really was" (Ranke). It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger....

W. Benjamin, "Theses on the Philosophy of History", 1970, p. 247

Chapter One

Introduction

In this book I would like to draw attention to what one is able to unearth when one studies the letters between Anna Freud and Ernest Jones, and especially those written between 1933 and 1939 and centring on the problems that were generated by the persecution of the Jews and the forced emigration of German and Austrian psychoanalysts during the Nazi era. Initially, they discuss the problems encountered by those psychoanalysts who lived in Berlin during the early 1930s; they then move on to consider the plight of those who lived in Austria, and who, after the Anschluss, found that their already precarious situation had become totally untenable.