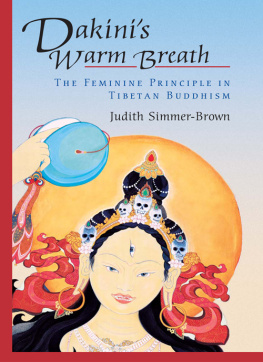

A comprehensive, scholarly, and intriguing study of dakini, the feminine principle of Tibetan Buddhism. A landmark study.

Library Journal

Simmer-Brown has written what is destined to be a classic among vajrayana practitioners, Buddhists of other schools, and readers interested in Buddhism.

Shambhala Sun

Dakinis Warm Breath is not only readable, but exhilaratingly lucid.

Tricycle: The Buddhist Review

A scholarly and fascinating exploration into the feminine principle in Tibetan Buddhism.

Bodhi Tree Book Review

A book-length discussion of dakinis, who are one of the most elusive aspects of Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism, is a welcome edition to the growing literature on symbols of the feminine in Buddhism. Simmer-Brown skillfully interweaves traditional stories with commentaries by contemporary Buddhist teachers to provide the most complete discussion of this topic to date.

Rita Gross, author of Buddhism after Patriarchy and Soaring and Settling: Buddhist Perspectives on Contemporary Social and Religious Issues

ABOUT THE BOOK

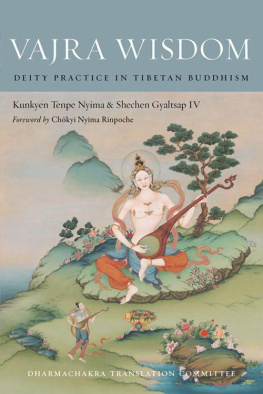

The primary emblem of the feminine in Tibetan Buddhism is the dakini, or sky-dancer, a semi-wrathful spirit-woman who manifests in visions, dreams, and meditation experiences. Western scholars and interpreters of the dakini, influenced by Jungian psychology and feminist goddess theology, have shaped a contemporary critique of Tibetan Buddhism in which the dakini is seen as a psychological shadow, a feminine savior, or an objectified product of patriarchal fantasy. According to Judith Simmer-Brownwho writes from the point of view of an experienced practitioner of Tibetan Buddhismsuch interpretations are inadequate.

In the spiritual journey of the meditator, Simmer-Brown demonstrates, the dakini symbolizes levels of personal realization: the sacredness of the body, both female and male; the profound meeting point of body and mind in meditation; the visionary realm of ritual practice; and the empty, spacious qualities of mind itself. When the meditator encounters the dakini, living spiritual experience is activated in a nonconceptual manner by her direct gaze, her radiant body, and her compassionate revelation of reality. Grounded in the authors personal encounter with the dakini, this unique study will appeal to both male and female spiritual seekers interested in goddess worship, womens spirituality, and the tantric tradition.

JUDITH SIMMER-BROWN, Ph.D., is professor and chair of the religious studies department at Naropa University (formerly the Naropa Institute), where she has taught since 1978. She has authored numerous articles on Tibetan Buddhism, Buddhist-Christian dialogue, and Buddhism in America. She is an Acharya (senior teacher) in the lineage of Chgyam Trungpa. A practicing Buddhist since 1971, she lives in Boulder, Colorado.

Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

Dakinis Warm Breath

THE FEMININE PRINCIPLE IN TIBETAN BUDDHISM

Judith Simmer-Brown

Shambhala

BOSTON & LONDON

2013

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

2001 by Judith Simmer-Brown

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Library of Congress catalogs the hardcover edition of this book as follows:

Simmer-Brown, Judith.

Dakinis warm breath: the feminine principle in Tibetan Buddhism/Judith Simmer-Brown.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2842-1

ISBN 978-1-57062-720-0 (alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-57062-920-4 (pbk.)

1. kin (Buddhist deity) 2. BuddhismChinaTibet. 3. FemininityReligious aspectsBuddhism. I. Title.

BQ4750.D33 S56 2001

294.342114dc21 00-046359

Contents

This book contains Sanskrit diacritics and special characters. If you encounter difficulty displaying these characters, please set your e-reader device to publisher defaults (if available) or to an alternate font.

PHOTOGRAPHS

FIGURES

W HEN I WAS NINETEEN, I was first enveloped by the feminine principle, albeit in a hidden form. As I arrived on the Delhi tarmac straight from Nebraska and inhaled the scent of smoke, urine and feces, rotting fruit, and incense, I knew I was home. From that moment on, the sway of brilliant saris, the curve of water jugs, the feel of chilis under my fingernails, and the pulse of street music called me back to something long forgotten. As I gazed into the faces of leprous beggars, wheedling hawkers, and the well-oiled rich, I was shocked into a certain equanimity I could not name. The only way I could express it was to say that I suddenly knew what it meant to be a woman. On subsequent trips, I have had similar responses, the slowing of my mind and a deep relaxation in the pores of my body, calling me from ambitions of daily life to an existence more basic and fundamental, calling me home.

As a graduate student in South Asian religion in the late sixties, I discovered feminism. For many years, my feminist journey paralleled my academic and spiritual ones, and I found few ways to truly link them. Looking back at my papers and essays, I can see that I was trying to find a place for myself as a woman in academe. At the same time I began Buddhist sitting meditation practice, zazen, in the Japanese St tradition. In my first teaching job, I was the only woman my academic department had ever hired. When I was inexplicably terminated, departmental memos gave as the reason that my husband was a university administrator and I didnt need the money. I joined a class action suit against the university and eventually won. During the turmoil, Buddhist meditation gave me a quiet center from which to ride out the maelstrom.

Later, eschewing another full-time academic appointment for full-time intervention with rape victims, my feminism emerged full blown. I saw myself burning in all womens rage, rage against the violence, the brutalization and objectification of us all. Even as I became outraged, I continued to sit. Alternating confrontation therapy with convicted rapists and long periods of intensive meditation, I learned that rage is bottomless, endless, the fuel for all-pervading suffering in the world. I began to feel directly the sadness at the heart of rage, sadness for all the suffering that peoplefemale and male, rape victim and rapisthave experienced. I knew then that feminism saw a part of the truth, but only a part. Having experienced my own suffering, I began to sense its origin and to glimpse its end.

That is when I came to teach Buddhist Studies at Nropa University, at the end of 1977. Several years earlier, I had met my teacher, Ven. Chgyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and recognized at once that I had everything to learn from him. He completely knew the rage and he knew the sadness, and yet he had not lost heart. He thoroughly enjoyed himself, others, and the world. And he introduced me to a journey in which I could explore rage, sadness, passion, and ambition and never have them contradict my identity as a woman and a practitioner. My feminist theories wilted in the presence of his humor and empathy, and my consuming interests turned to Buddhist practice, study, and teaching.

Next page