One

THE NATIVE AMERICANS

The many villages of the Mutsun Indians gathered together once or twice each year for trading and collecting acorns, pine nuts, and seeds gathered from the hills surrounding the valley. For thousands of years, the Mutsuns had developed skills in making just about everything they needed for survival. What they did not have on hand they sought through trade with neighboring villages. The trading of shell beads, feathers, and seafood was carried out with the coastal Native Americans; the trading of minerals and timber occurred with the tribes of the San Joaquin Valley. Strong, straight branches were needed for making arrows and obsidian and chert for points. These materials came from the Central Valley and the foothills of the Sierras.

The San Juan Valley included many freshwater ponds fed by rivers and streams. Mutsuns fished these pools using woven nets filled with yorbe del pescado, an herbal mixture that acted as an opiate, stunning the fish, which then floated to the surface to be gathered. Another way of catching fish was to stretch a net filled with leaves across a narrow part of a pond and have the children get into the water and scare the fish to the net.

In addition to fish, the meat of deer, rabbits, and other small game were sources of food. Bears were believed to be sacred and were therefore seldom killed. The tree squirrel, considered a delicacy, was caught by locating its nest, putting mud over the upper hole, and starting a smoky fire in the lower hole. The asphyxiated animal was then removed, cleaned, and roasted. The skins and fur were made into clothing and the bones were used for tools to cut and sew.

The Mutsuns lived in thatched huts made from tulles that grew near the many ponds and streams. Grasses, thin tree branches, and pine needles were woven into baskets for cooking, storing food, and carrying goods. Gift baskets were often decorated with abalone shells from the coast. Few baskets have survived; however, two Mutsun baskets are presently in the collections of the mission museum.

This photograph, on exhibit at the state park, depicts Barbara Serra Solarsano, a Mutsun Indian. Baptized at the mission, she was given the name Barbara after an early saint. her maiden name, Serra, was given to her in honor of padre Junipero Serra, founder of the California missions.

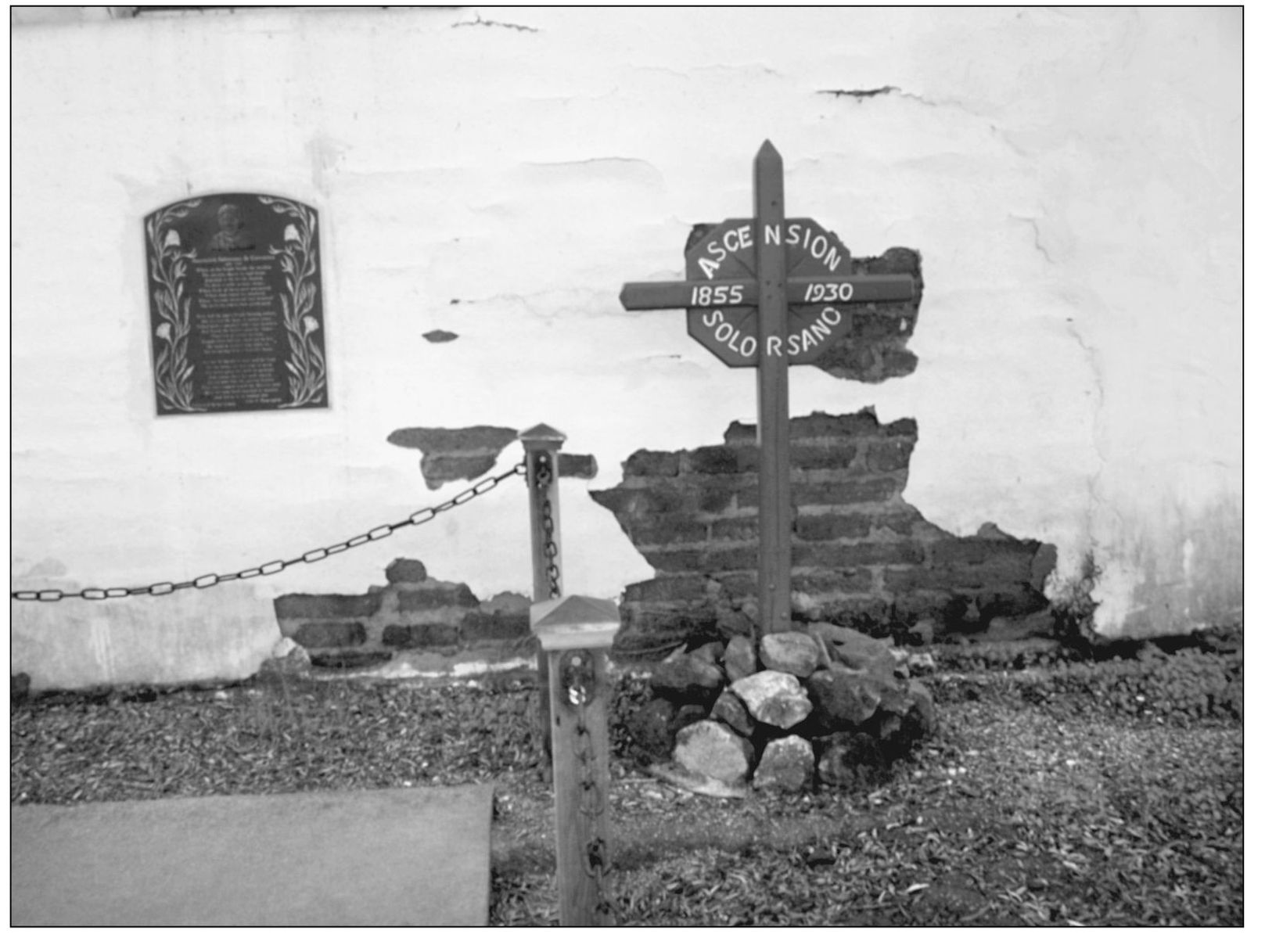

Doa Ascension Solarsano de Cervantes, daughter of Barbara Serra, was born in 1855 and baptized at the mission. When she died in 1930, she was buried along the church wall in the American Indian cemetery. prior to her death, ethnologist and linguist John peabody harrington spent some months with her gathering the language, stories, and songs of her Mutsun heritage. harrington made many recordings of the language, as well copious written notes. Unfortunately the records were accidentally broken before arrival at the Smithsonian. harringtons notes, however, are stored there.

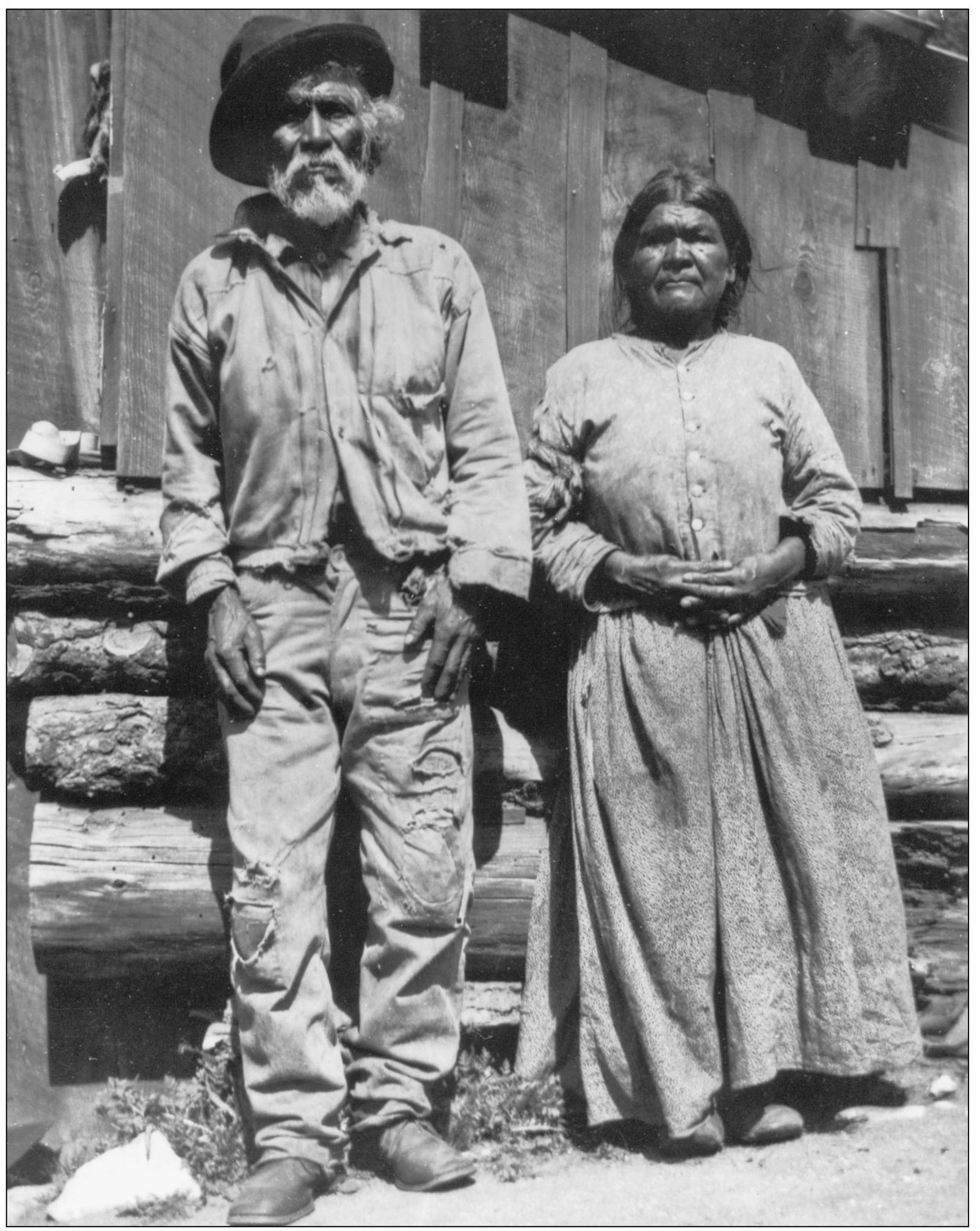

This 1906 photograph shows Joe Wellina, who lived to be 110, and Maria Garcia, both Mutsun Indians.

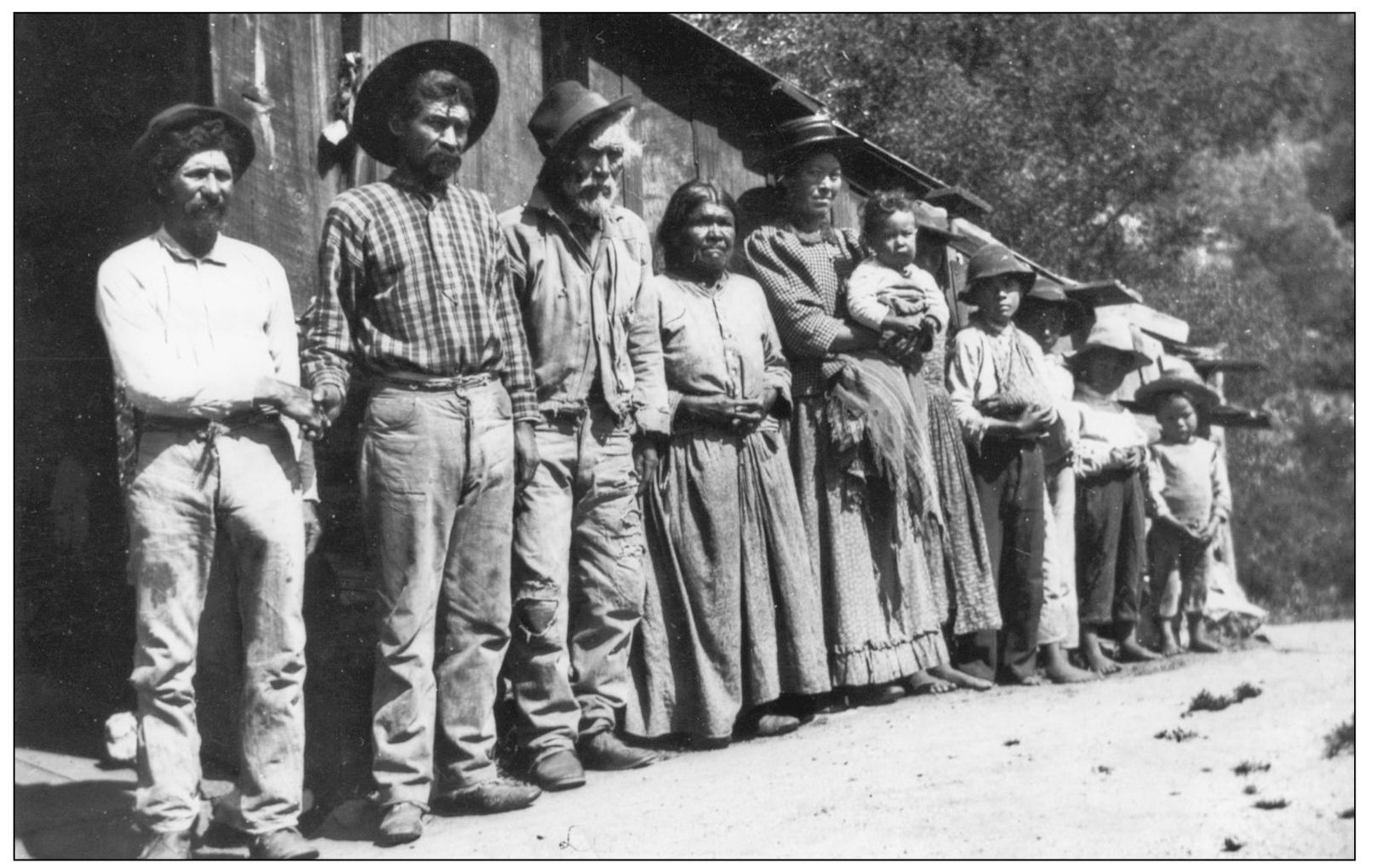

Mutsun Indians, pictured in 1906, stand in front of a building constructed after their home burned. The man in the plaid shirt is Sebastian Garcia, husband of Maria Garcia, fourth from the left. Between them is Joe Wellina. Next to Maria are some of her 12 children

These baskets, made by Barbara Serra, were donated to the mission by her great-grandson Tony Corona. According to Tony, his grandmother Ascension used them. The large, almost flat winnowing basket helped in gleaning dried beans from the fields. he said, Grandma Ascension kept her tobacco in the small basket. Small baskets were traditionally used as gift baskets containing something of value such as feathers or beads. The hole in the large basket was caused by mice while in storage.

Two

THE SPANISH MISSION PERIOD

After the location for the San Juan Bautista Mission was chosen in 1795 and permission was given to begin construction, the plaza at the heart of town was the first thing to take shape. Adobe buildings were constructed around a central courtyard. These buildings housed work and storage rooms, residences for the padres, and barracks for the soldiers. Construction progressed smoothly until October 1800. That month, there were, on average, six earthquakes a day for 30 days. The buildings that had been erected since 1797 were destroyed or so severely damaged that officials decided to rebuild the entire complex. Construction of the new church began in 1803 and was completed nine years later. When finished, it was the largest of all the California mission churches.

The mission prospered because the land was fertile and crops and herds increased. however, disease decimated the Mutsun Indian population over the first 20 years of the 19th century. During these years, the population of the mission and the town was reduced by some 70 percent. This created a shortage of laborers to maintain the mission complex. European diseases were the principle causes of death, but gastric diseases also killed many.

From the beginning, unmarried women were required to live in a special building called a convento . During the day, these women were allowed to work and move throughout the community, but at night, they were required to return to the convento, where they were locked in. When a young man wanted to marry, he would tell the name of his intended to the padre. Announcements of the intended marriage were made on Sunday at mass and preparations were made for the wedding. After the wedding, the couple was given a house and each was welcomed as an adult member of the Mutsun Indian community.