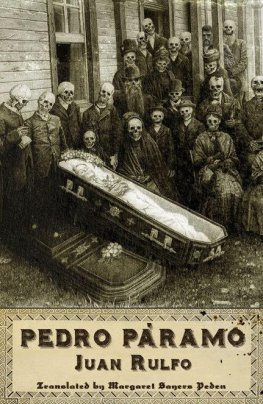

I came to Comala because I had been told that my father, a man named Pedro Paramo lived there. It was my mother who told me. And I had promised her that after she died I would go see him. I squeezed her hands as a sign I would do it. She was near death, and I would have promised her anything. Dont fail to go see him, she had insisted. Some call him one thing, some another. Im sure he will want to know you. At the time all I could do was tell her I would do what she asked, and from promising so often I kept repeating the promise even after I had pulled my hands free of her death grip.

Still earlier she had told me:

Dont ask him for anything. Just whats ours. What he should have given me but never did. Make him pay, son, for all those years he put us out of his mind.

I will, Mother.

I never meant to keep my promise. But before I knew it my head began to swim with dreams and my imagination took flight. Little by little I began to build a world around a hope centered on the man called Pedro Paramo, the man who had been my mothers husband. That was why I had come to Comala.

It was during the dog days, the season when the August wind blows hot, venomous with the rotten stench of saponaria blossoms.

The road rose and fell. It rises or falls depending on whether youre coming or going. If you are leaving, its uphill; but as you arrive its downhill.

What did you say that town down there is called?

Comala, senor.

Youre sure thats Comala?

Im sure, senor.

Its a sorry-looking place, what happened to it?

Its the times, senor.

I had expected to see the town of my mothers memories, of her nostalgia nostalgia laced with sighs. She had lived her lifetime sighing about Comala, about going back. But she never had. Now I had come in her place. I was seeing things through her eyes, as she had seen them. She had given me her eyes to see. Just as you pass the gate of Los Colimotes theres a beautiful view of a green plain tinged with the yellow of ripe corn. From there you can see Comala, turning the earth white, and lighting it at night. Her voice was secret, muffled, as if she were talking to herself. Mother.

And why are you going to Comala, if you dont mind my asking? I heard the man say.

Ive come to see my father, I replied.

Umh! he said.

And again silence.

We were making our way down the hill to the clip-clop of the burros hooves. Their sleepy eyes were bulging from the August heat.

Youre going to get some welcome. Again I heard the voice of the man walking at my side. Theyll be happy to see someone after all the years no ones come this way.

After a while he added: Whoever you are, theyll be glad to see you.

In the shimmering sunlight the plain was a transparent lake dissolving in mists that veiled a gray horizon. Farther in the distance, a range of mountains. And farther still, faint remoteness.

And what does your father look like, if you dont mind my asking?

I never knew him, I told the man. I only know his name is Pedro Paramo.

Umh! that so?

Yes. At least that was the name I was told.

Yet again I heard the burro drivers Umh!

I had run into him at the crossroads called Los Encuentros. I had been waiting there, and finally this man had appeared.

Where are you going? I asked.

Down that way, senor.

Do you know a place called Comala?

Thats the very way Im going.

So I followed him. I walked along behind, trying to keep up with him, until he seemed to remember I was following and slowed down a little. After that, we walked side by side, so close our shoulders were nearly touching.

Pedro Paramos my father, too, he said.

A flock of crows swept across the empty sky, shrilling caw, caw, caw.

Up-and downhill we went, but always descending. We had left the hot wind behind and were sinking into pure, airless heat. The stillness seemed to be waiting for something.

Its hot here, I said.

You might say. But this is nothing, my companion replied. Try to take it easy. Youll feel it even more when we get to Comala. That town sits on the coals of the earth, at the very mouth of hell. They say that when people from there die and go to hell, they come back for a blanket.

Do you know Pedro Paramo? I asked.

I felt I could ask because I had seen a glimmer of goodwill in his eyes.

Who is he? I pressed him.

Living bile, was his reply.

And he lowered his stick against the burros for no reason at all, because they had been far ahead of us, guided by the descending trail.

The picture of my mother I was carrying in my pocket felt hot against my heart, as if she herself were sweating. It was an old photograph, worn around the edges, but it was the only one I had ever seen of her. I had found it in the kitchen safe, inside a clay pot filled with herbs: dried lemon balm, castilla blossoms, sprigs of rue. I had kept it with me ever since.

It was all I had. My mother always hated having her picture taken. She said photographs were a tool of witchcraft. And that may have been so, because hers was riddled with pinpricks, and at the location of the heart there was a hole you could stick your middle finger through.

I had brought the photograph with me, thinking it might help my father recognize who I was.

Take a look, the burro driver said, stopping. You see that rounded hill that looks like a hog bladder? Well, the Media Luna lies right behind there. Now turn that way. You see the brow of that hill? Look hard. And now back this way. You see that ridge? The one so far you cant hardly see it? Well, all thats the Media Luna.

From end to end. Like they say, as far as the eye can see. He owns ever bit of that land.

Were Pedro Paramos sons, all right, but, for all that, our mothers brought us into the world on straw mats. And the real joke of it is that hes the one carried us to be baptized. Thats how it was with you, wasnt it?

I dont remember.

The hell you say!

What did you say?

I said, were getting there, senor.

Yes. I see it now. What could it have been?

That was a correcaminos, senor. A roadrunner. Thats what they call those birds around here.

No. I meant I wonder what could have happened to the town? It looks so deserted, abandoned really. In fact, it looks like no one lives here at all.

It doesnt just look like no one lives here. No one does live here.

And Pedro Paramo?

Pedro Paramo died years ago.

It was the hour of the day when in every little village children come out to play in the streets, filling the afternoon with their cries. The time when dark walls still reflect pale yellow sunlight.

At least that was what I had seen in Sayula, just yesterday at this hour. Id seen the still air shattered by the flight of doves flapping their wings as if pulling themselves free of the day.

They swooped and plummeted above the tile rooftops, while the childrens screams whirled and seemed to turn blue in the dusk sky.

Now here I was in this hushed town.Tcould hear my footsteps on the cobbled paving stones. Hollow footsteps, echoing against walls stained red by the setting sun.

This was the hour I found myself walking down the main street.

Nothing but abandoned houses, their empty doorways overgrown with weeds. What had the stranger told me they were called? La gobernadora, senor. Creosote bush. A plague that takes over a persons house the minute he leaves. Youll see.

As I passed a street corner, I saw a woman wrapped in her rebozo; she disappeared as if she had never existed. I started forward again, peering into the doorless houses. Again the woman in the rebozo crossed in front of me.

Evening, she said.