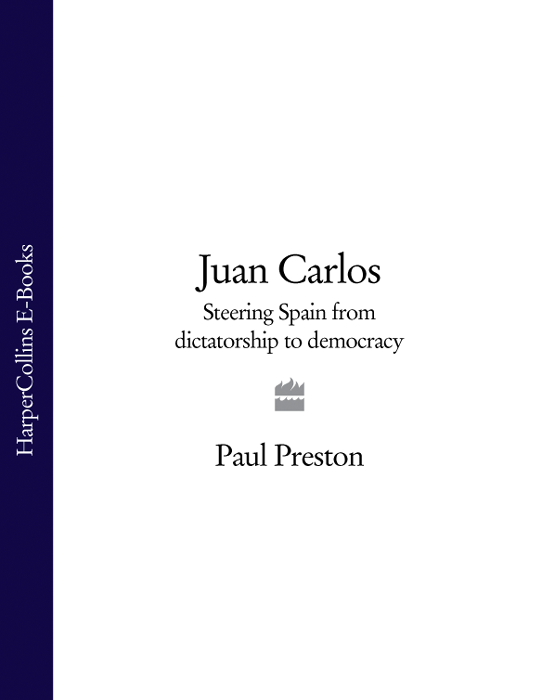

C HAPTER O NE

In Search of a Lost Crown

19311948

There are two central mysteries in the life of Juan Carlos, one personal, the other political. The key to both lies in his own definition of his role: For a politician, because he likes power, the job of King seems to be a vocation. For the son of a King, like me, its something altogether different. Its not a question of whether I like it or not. I was born to it. Ever since I was a child, my teachers have taught me to do things that I didnt like. In the house of the Borbns, being King is a profession. In those words lies the explanation for what is essentially a life of considerable sacrifice. How else is it possible to explain the apparent equanimity with which Juan Carlos accepted the fact that his father, Don Juan, to all intents and purposes sold him into slavery? In 1948, in order to keep the possibility of a Borbn restoration in Spain on Francos agenda, Don Juan permitted his son to be taken to Spain to be educated at the will of the Caudillo. In a normal family, this act would be considered to be one of cruelty, or at best, of callous irresponsibility. But the Borbn family was not normal and the decision to send Juan Carlos away responded to a higher dynastic logic. Nevertheless, the tension between the needs of the human being and the needs of the dynasty lies at the heart of the story of the distance between the fun-loving boy, Juanito de Borbn, and the rather stiff prince Juan Carlos with his perpetually sad look. The other, rather more difficult puzzle, is how a prince emanating from a family with considerable authoritarian traditions, obliged to function within rules invented by General Franco, and brought up to be the keystone of a complex plan for the continuity of the dictatorship should have committed himself to democracy.

On 14 April 1931, on his painful journey from Madrid, via Cartagena, into exile in France, the King was accompanied by his cousin, Alfonso de Orlens Borbn. The Queen, Victoria Eugenia of Battenburg, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, was escorted into exile by her cousin, Princess Beatrice of Saxe-Coburg, the wife of Alfonso de Orlens Borbn.

In addition to the blow of exile, Alfonso XIII suffered considerable personal sadness. Without the scenery of the palace and the supporting cast of courtiers, the emptiness of his relationship with Victoria Eugenia was increasingly exposed. Not long after their arrival at Fontainebleau, the King remonstrated with the Queen about her closeness to the Duke and Duchess de Lcera who had accompanied her into exile. The marriage of the Duke, Jaime de Silva Mitjans, and the lesbian Duchess, Rosario Agrelo de Silva, was a sham but they stayed together because both were in love with the Queen. Despite persistent rumours, which niggled at Alfonso XIII, the Queen always vehemently denied that she and the Duke had been lovers. Nevertheless, when the bored Alfonso XIII took a new lover in Paris and the Queen in turn remonstrated with him, he tried to divert the onslaught by throwing in her face the alleged relationship with Lcera. She denied it but, as tempers rose, he demanded that she choose between himself and Lcera. Fearful of losing their support, on which she had come to rely, she replied, by her own account, with the fateful words, I choose them and never want to see your ugly face again. There would be no going back.

Another reason for Alfonsos long-deteriorating relationship with Victoria Eugenia was the fact that she had brought haemophilia into the family. The couples eldest son, Alfonso, was of dangerously delicate health. He was haemophilic and, according to his sister, the Infanta Doa Cristina, the slightest knock caused him terrible pain and would paralyse part of his body. He often could not walk unaided and lived in constant fear of a fatal blow. When the recently appointed Director General of Security, Emilio Mola, made his courtesy visit to the palace in February 1930, he was shocked: I also visited the Prncipe de Asturias [the Spanish equivalent of the Prince of Wales] and only then did I fully understand the intimate tragedy of the royal family and comprehend Alfonso formally renounced his right to the throne on n June 1933 in return for his fathers permission to contract a morganatic marriage with an attractive but frivolous girl he had met at the Lausanne clinic where he was receiving treatment. Edelmira Sampedro y Robato was the 26-year-old daughter of a rich Cuban landowner.

Immediately following his eldest sons renunciation of his dynastic rights, Alfonso XIII arranged for a number of prominent monarchists to put pressure on his second son, Don Jaime, to follow his brothers example. Don Jaime was deaf and dumb the result of a botched operation when he was four. Cut off from the world, both by dint of his royal status and his deafness, he had grown into a singularly immature young man. The monarchist leader Jos Calvo Sotelo persuaded him that his inability to use the telephone would significantly diminish his capacity to take part in anti-Republican conspiracies.

In his 1933 letter to his father, Don Jaime wrote: Sire. The decision of my brother to renounce, for himself and his descendants, his rights to the succession of the crown has led me to weigh the obligations that thus fall on me I have decided on a formal and explicit renunciation, for me and for any descendants that I might have, of my rights to the throne of our fatherland.

As a result of the successive renunciations of Alfonso and Jaime, the title of Prncipe de Asturias fell upon Alfonso XIIIs third son, the 20-year-old Don Juan. When he received his fathers telegram informing him of this, Don Juan was a serving officer in the Royal Navy on HMS Enterprise, anchored in Bombay. Because he realized that his new role would eventually involve him leaving his beloved naval career, he accepted only after some delay. In May 1934, he was promoted to sub-lieutenant and in September, he joined the battleship HMS Iron Duke. In March 1935, he passed the examinations in naval gunnery and navigation which opened the way to his becoming a lieutenant and being eligible to command a vessel. However, that would mean renouncing his Spanish nationality, something he was not prepared to do. His uncle, King George V, granted him the rank of honorary Lieutenant RN.

Don Juan did not emulate his elder brothers disastrous marriages. On 13 January 1935, at a party given by the King and Queen of Italy on the eve of the marriage of the Infanta Doa Beatriz to Prince Alessandro Torlonia, Prince di Civitella Cesi, Don Juan had met the 24-year-old Mara de las Mercedes Borbn Orlans. Having faced the problem of his eldest sons unsuitable marriage, Alfonso XIII was delighted when Don Juan began to The newly appointed Prncipe de Asturias and his new bride settled at the Villa Saint Blaise in Cannes in the south of France. There, he quickly made contact with the leading monarchist politicians who were involved in anti-Republican plots.