We thank the following colleagues and friends for encouraging support, fructiferous collaboration, and stimulating discussions:

Mara I. Abasolo, Ulises Acua, mit Akbey, Marco A. Alvarez, Jos L. Bella, Gabriel Bertolesi, Thomas Breitenbach, Magdalena Caete, Paul J. CaraDonna, Elisa Carrasco, Adriana Casas, Lucas L. Colombo, Pedro Del Castillo, Edgardo N. Durantini, Jrgen Elvert, Jess Espada, Pedro Esponda, Juan M. Ferrer, Sergio Galaz-Leiva, Antonio Gmez, Jorge Herkovits, Richard W. Horobin, Amy M. Iler, Angeles Juarranz, Markus Kempf, John A. Kiernan, Claudia Lanari, Jos A. Lisanti, Daniel M. Lombardo, Isabel Lthy, Maria Luiza S. Mello, Roberto Mezzanotte, Arturo Morales, Karen n Mheallaigh, Santi Nonell, Claus Pelling, Peter R. Ogilby, Carolina Oll, Cristina Ortega-Villasante, Viviana Rivarola, Antonio Romero, Steven E. Ruzin, Sergio H. Simonetta, Alberto J. Solari, Arnaldo T. Soltermann, Carlos Soez, Cristina Soez, Francisco Vicente Pedrs, Benedicto C. Vidal, Angeles Villanueva, and Clara I. Trigoso.

Finally, our apologies to many other people lacking explicit mention but also very interested in this e-book and always supporting our research work.

Our institutional acknowledgements go to the following institutions for their help and support:

JCS - Max-Planck-Institut fr Biologie, Tbingen, Germany, Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Autonomous University of Madrid (grant CTQ2013-48767-C3-3-R from the Ministerio de Economa y Competitividad, Spain), Institute of Research and Technology in Animal Reproduction, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, University of Buenos Aires, and Institute of Environmental Sciences and Health, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

ABC - Aarhus Institute of Advanced Studies (AIAS), Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark; Marie Skodowska-Curie actions - Research Fellowship Programme (AIAS-COFUND programme 609033).

Juan Carlos Stockert

Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences,

Autonomous University of Madrid,

Spain

Institute of Oncology Angel H. Roffo, Research Area,

University of Buenos Aires,

Argentina

Institute of Research and Technology in Animal Reproduction,

Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, University of Buenos Aires,

Argentina

Introduction

Juan C. StockertDepartment of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Autonomous University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

Abstract

This book tries to be a guide for understanding fluorescence microscopy, and explaining its chemical and physical principles for workers in biomedical sciences, especially those with limited expertise in chemistry and physics. In contrast to early morphological studies, considerable background of physics and chemistry is at present necessary to make fluorescence microscopy a more fruitful technique. In this book we therefore attempt to simplify and make understandable the basis of fluorescence reactions and their biomedical applications. When possible, mechanistic approaches have been introduced regarding dye affinity and fluorescent selectivity. To make the text more didactic and amenable, cell and tissue pictures, diagrams, graphs and chemical structures are included. Obviously, overlapping of several issues concerning fluorochromes and fluorescence techniques will be found along chapters. As an example, consider binding of a fluorescent ligand to a biomolecule. This can be studied from the point of view of (1) ligand properties and binding, (2) substrate structure and affinity, (3) reaction methodology, mechanisms, instrumentation, etc. In turn, ligands can be simple molecules (fluorochromes, vital probes), macromolecules (phycobilins, fluorescent proteins), or multi-molecular complexes (labeled IgG, lectins, oligonucleotides), in which different fluorescent labels are used for visualizing a great variety of biological substrates.

Keywords: Amphoteric dyes, Dark-field illumination, Fluorescent labels, Hematoxylin, Hydrophobic dyes, Indigo, Ionic dyes, Lignum Nephriticum, Mordant dyes, Nile blue, Orcein, Photoactive dyes, Polarization microscopy, Reactive dyes, Solvent dyes.

1. FLUORESCENCE METHODOLOGY: GENERAL ASPECTS

At present, there is almost no biomedical field in which fluorescence methods are not applied. Research professionals have been increasingly interested in this methodology, and now new concepts, instruments and techniques have developed rapidly leading to constant progress in the design and application of fluorescence methods. The literature of fluorescence methodology is so extensive that only the most relevant references are included in each chapter. Likewise, no special emphasis is given to precise chemical description of biological substrates (i.e. lipids, polysaccharides, nucleic acids, proteins, etc.), because these are explained in detail in textbooks of biochemistry and cell biology.

On the other hand, the number of fluorescent images is overwhelming [ ), and other commercial sources.

Classic books should be consulted for more detailed accounts in the fields of light, color and chemistry of dyes [].

Here the terms, fluorescent dye and fluorochrome apply indistinctly to any fluorescent compound used for staining fixed cells or labeling live cells. The terms, luminophores and fluorophores are also used, meaning a chromophore (part of a molecule) that absorbs UV or visible light and emits light of a longer wavelength (i.e. fluorescence). Fluorescent probes are vital fluorochromes that localize selectively in some cell or tissue structures. Sometimes they are referred to as fluoroprobes. A fluorescent label indicates a fluorochrome that is covalently or otherwise strongly bound to a biomolecule. The generic term staining is often applied to denote the use of a fluorochrome in fluorescence microscopy, i.e. acridine orange staining.

Some misleading concepts should be taken into account and corrected regarding fluorescence microscopy. Often it is claimed that to observe fluorescence, ultraviolet (UV) excitation is required. This is true for only some fluorescent compounds, because others need blue or green excitation. Fluorochromes are sometimes abbreviated as fluors. Immunofluorescence microscope is a bad name, because there is no specific microscope to be used for this technique. Description of excitation filters by their applications instead wavelength (i.e. Texas red excitation/emission filters, DAPI channel, or DAPI cube) is another ambiguous and imprecise practice. High brightness is often taken as a synonym of strong affinity for a given substrate, but the emission intensity is only based on the fluorochrome chemistry and binding mode. Therefore, some prejudices and myths in the fluorescence methodology should be corrected.

2. COLOR AND ENERGY SPECTRUM

Color is the visual impression produced by light emitted by a luminous source or reflected from a material. Sometimes, a color is often subjectively described by comparing it with the color of a familiar object. A perceived color is largely dependent on the type of illumination and light intensity (e.g. brown is not a spectral color but a very dark orange). Clearly defined assessment of colored objects is possible through objective measurements and chromaticity diagrams.

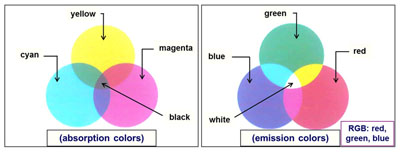

Cyan, yellow and magenta are the three primary colors. All the remaining solid (absorption) colors can be obtained by mixing the primary ones. Techniques for color restitution in trichromy are shown in Fig. ().

Fig. (1.1)) Diagram of primary colors (absorption and emission), and trichromic RGB synthesis.