I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life...

Henry David Thoreau, Walden

Introduction

We live in an age of miracles so commonplace that it can be difficult to see them as anything other than part of the daily texture of living. This is the technology writer and theorist Kevin Kelly, blogging in August 2011:

Ive had to persuade myself to believe in the impossible more often... Twenty years ago if I had been paid to convince an audience of reasonable, educated people that in twenty years time wed have street and satellite maps for the entire world on our personal hand held phone devices for free and with street views for many cities I would not be able to do it. I could not have made an economic case for how this could come about for free. It was starkly impossible back then.

The impossible facts of our age are only just beginning. Ahead of us lie new forms of collaboration and interaction whose outlines we are, perhaps, beginning to glimpse in the fact that the internet-connected phones increasingly found in every pocket are more powerful than most computers were ten years ago. In another decades time, billions of people will have at their fingertips the kind of resources that only governments commanded twenty years ago.

The pace of these changes is another unprecedented thing. Television and radio have been with us for over a century; print for more than 500 years. Yet in just two decades, we have moved from the public opening-up of the internet to its connection to more than two billion people; and it has been just three decades between the launch of the first commercial cellular-phone system and the connection of more than five billion active accounts.

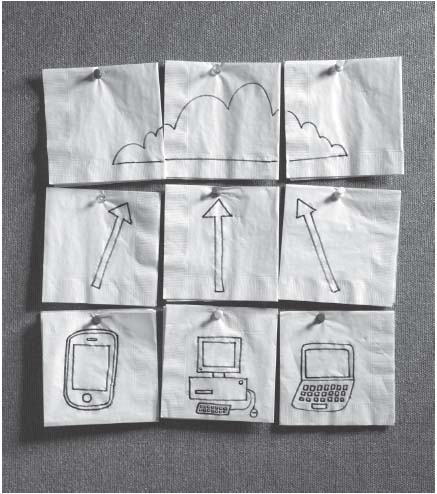

This smart global network is likely, in the future, to connect not only us, but many of the objects in our lives from cars and clothes to food and drink. Through smart chips and centralized databases, we are gaining an unprecedented kind of connection not only to each other, but to the manufactured world around us: its tools, its shared spaces, its patterns of action and reaction. And with all of this comes new information about the world, in new kinds of quantities: information about where we are, what we are doing, and what we are like.

What are we to make of this information? And, equally importantly, what is already being made of it by others by governments; by corporations; by activists, criminals, law-enforcers and creators? Knowledge and power have always been closely entwined. Today, though, information and the infrastructure through which it flows represent not only power, but a new kind of economic and social force.

Intellectually, socially and legislatively, we are lagging years, if not decades, behind the facts of the present. Generationally, the divide between those natives born into a digital era and those who grew up before it can seem a chasm across which common understandings and shared values are difficult to articulate.

This book examines the question of what it may mean for all of us not simply to exist but to thrive within a digital world; to live deep, in Thoreaus phrase, and to make the most of the unfolding possibilities of our times.

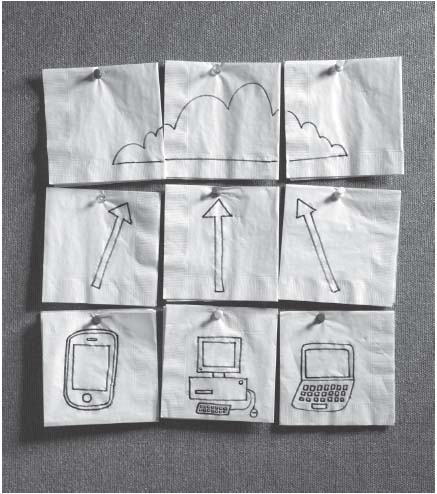

Living in a data cloud: smart networks are starting to connect not only us, but everything from cars to clothing.

Exploring these possibilities is like exploring a new city or continent. We are entering a place where human nature remains the same, but the structures shaping it are alien. Todays digital world is not simply an idea or a set of tools, any more than a modern digital device is simply something switched on for leisure or pleasure. Rather, for an ever-increasing number of people, it is a gateway to the place where leisure and labour alike are rooted: an arena within which we seamlessly juggle friendships, media, business, shopping, research, politics, play, finance, and much else besides.

When it comes to the question of thriving, my aim is to trace two interwoven stories: first, how we as individuals can thrive in the digital world; and second, how society can help us both to realize our potential in this world, and to relate to others in as fully human a way as possible.

These stories both begin in the same place, with the history of digital machines. I then go on to explore one of the most central questions of the present state of technology: what it means to be able to say no as well as yes to the tools in our lives, and to make the best of ourselves both by using technology and by deliberately carving out time for not using it.

Ill also talk about those challenges that almost all of us whether we know it or not grapple with every day: issues of personal identity, privacy, communication, attention, and the regulation of all the above. If there is a common thread here, it is the question of how individual experience fits into the new kind of collective life of the twenty-first century: how what I am relates to what others know of me, what I share with those others, and what can remain personal and private.

The second half of this book examines the cultural and political structures encompassing these interests, and what the contracts of decent digital citizenship might look like. Finally, Ill return to that most central of questions: what it means to live well in an age that holds unparalleled opportunities both for narcissism and for connection to others.

The nature of digital technology is as protean as our own, and can play many parts in our lives: facilitator, library, friend, seducer, comfort, prison. Ultimately, though, all of its shifting screens are also mirrors, in which we have the opportunity to see ourselves and each other as never before. Or, of course, we can look away.

1. From Past to Present

The brief story of human interactions with digital technologies has been one of steadily increasing intimacy: of the integration, within half a century, of a startlingly new kind of tool into the heart of billions of lives.

The first electronic digital computers, developed in the 1940s, were vast and dauntingly complex machines, devised and operated by some of the worlds finest minds: pioneers like Alan Turing, whose theoretical and practical work helped the British to decode encrypted German messages during the Second World War.

The next generation of computers, mainframes, arose in the late 1950s. Existing largely within academic and military institutions, mainframes still occupied entire rooms and were also the province of specialists their inputs taking the form of highly abstracted commands, their outputs meaningless to anyone not versed in computer science.

All this began to change in the 1970s, with the rise of the microprocessor and the arrival of the first computers in ordinary homes rather than laboratories. Thomas Watson, the president of IBM, is famously reported to have said in 1943. I think there is a world market for maybe five computers. Whether he made this claim or not (no less an authority than Wikipedia declares theres scant evidence that he did), when the worlds first personal computer was released as a kit in 1971, nobody expected the domestic market for such machines to run far beyond a few thousand enthusiasts.

Next page