For Mark Fairclough (Dad)

Introduction

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the handbook that most psychiatrists and many psychotherapists use to define the types and shades of insanity, you will find numerous personality disorders described. Despite this huge variety, and despite the proliferation of defined disorders in successive editions, these definitions fall into just two main groups. In one group are the people who have strayed into chaos and whose lives lurch from crisis to crisis; in the other are those who have got themselves into a rut and operate from a limited set of outdated, rigid responses. Some of us manage to belong to both groups at once. So what is the solution to the problem of responding to the world in an over-rigid fashion, or being so affected by it that we exist in a continual state of chaos? I see it as a very broad path, with many forks and diversions, and no single right way. From time to time we may stray too far to the over-rigid side, and feel stuck; few of us, on the other hand, will get through life without occasionally going too far to the other side, and experiencing ourselves as chaotic and out of control. This book is about how to stay on the path between those two extremes, how to remain stable and yet flexible, coherent and yet able to embrace complexity. In other words, this book is about How to Stay Sane.

I cannot pretend that there is a simple set of instructions that can guarantee sanity. Each of us is the product of a distinctive combination of genes, and has experienced a unique set of formative relationships. For every one of us who needs to take the risk of being more open, there is another who needs to practise self-containment. For each person who needs to learn to trust more, there is another who needs to experiment with more discernment. What makes me happy might make you miserable; what I find useful you might find harmful. Specific instructions about how to think, feel and behave thus offer few answers. So instead I want to suggest a way of thinking about what goes on in our brains, how they have developed and continue to develop. I believe that if we can picture how our minds form, we will be better able to re-form the way we live. This practice of thinking about the brain has helped me and some of my clients to become more in charge of our lives; there is a chance, therefore, that it may resonate with you too.

Plato compares the soul to a chariot being pulled by two horses. The driver is Reason, one horse is Spirit, the other horse is Appetite. The metaphors we have used throughout the ages to think about the mind have more or less followed this model. My approach is just such another version, and is influenced by neuroscience in conjunction with other therapeutic approaches.

Three Brains in One

In recent years, scientists have developed a new theory of the brain. They have begun to understand that it is not composed of one single structure but of three different structures, which, over time, come to operate together but yet remain distinct.

The first of these structures is the brain stem, sometimes referred to as the reptilian brain. It is operational at birth and is responsible for our reflexes and involuntary muscles, such as the heart. At certain moments, it can save our lives. When we absentmindedly step into the path of a bus, it is our brain stem that makes us jump back onto the pavement before we have had time to realize what is going on. It is the brain stem that makes us blink our eyes when fingers are flicked in front of them. The brain stem will not help you do Sudoku but at a basic, essential level, it keeps you alive, allows you to function and keeps you safe from many kinds of danger.

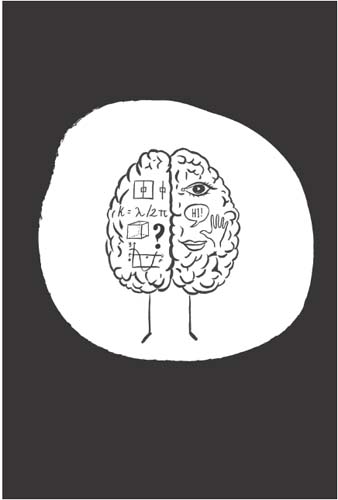

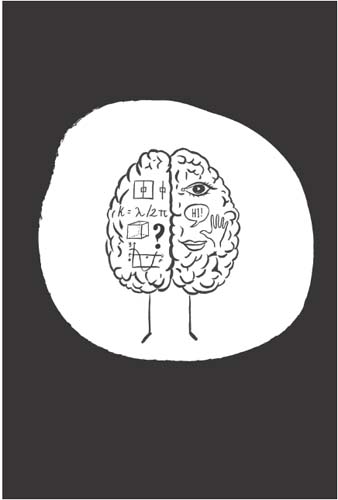

The other two structures of the brain are the mammalian, or right, brain and the neo-mammalian, or left, brain. Although they continue to develop throughout our lives, both of these structures do most of their developing in our first five years. An individual brain cell does not work on its own. It needs to link with other brain cells in order to function. Our brain develops by linking individual brain cells to make neural pathways. This linking happens as a result of interaction with others, so how our brain develops has more to do with our earliest relationships than with genetics; with nurture rather than nature.

This means that many of the differences between us can be explained by what regularly happened to us when we were very little. Our experiences actually shape our brain matter. To cite an extreme case from legend, if we do not have a relationship with another person in the first years of life but are nurtured by, say, a wolf instead, then our behavioural patterns will be more wolf-like than human.

In our first two years, the right brain is very active while the left is quiescent and shows less activity. However, in the following few years development switches; the right brains development slows and the left begins a period of remarkable activity. Our ways of bonding to others; how we trust; how comfortable we generally feel with ourselves; how quickly or slowly we can soothe ourselves after an upset have a firm foundation in the neural pathways laid down in the mammalian right brain in our early years. The right brain can therefore be thought of as the primary seat of most of our emotions and our instincts. It is the structure that in large part empathizes with, attunes to and relates to others. The right brain not only develops first, it also remains in charge. With one glance, one sniff, the right brain takes in and makes an assessment of any situation. As the Duke of Gloucester says in Shakespeares King Lear, when he looks about him: I see it feelingly.

What we call the left brain can be thought of as the primary language, logic and reasoning structure of our brain. We use our left brain for processing experience into language, to articulate our thoughts and ideas to ourselves and others and to carry out plans. Evidence-based science has been developed using the skills of the left brain, as have the sorting-and-ordering disciplines of taxonomy, philosophy and philology.

As I have said, in the first two years of life, left-brain development is much slower than in the right brain, which is why the foundations for our personalities are already laid down before the left brain, with its capacity for language and logic, has the ability to influence them. This could be why the right brain tends to remain dominant. You may be aware of the influence of both what I am calling the left and the right brains when you experience the familiar dilemma of having very good reasons to do the sensible thing, but find yourself doing the other thing all the same. The apparently sensible part of you (your left brain) has the language, but the other part (your right brain) often appears to have the power.

When we are babies our brains develop in relationship with our earliest caregivers. Whatever feelings and thought processes they give to us are mirrored, reacted to and laid down in our growing brains. When things go well, our parents and caregivers also mirror and validate our moods and mental states, acknowledging and responding to what we are feeling. So around about the time we are two, our brains will already have distinct and individual patterns. It is then that our left brains mature sufficiently to be able to understand language. This dual development enables us to integrate our two brains, to some extent. We become able to begin to use the left brain to put into language the feelings of the right.

Next page