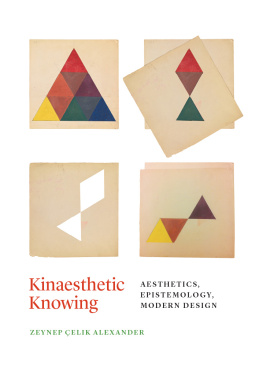

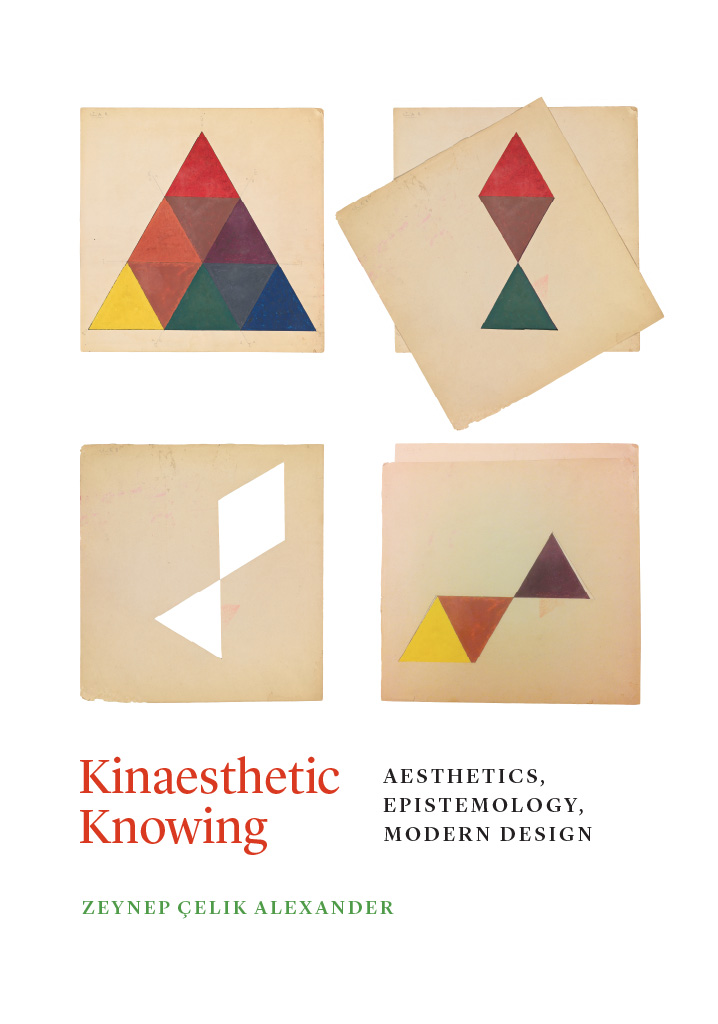

Kinaesthetic Knowing

Aesthetics, Epistemology, Modern Design

Zeynep elik Alexander

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2017 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-48520-1 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-48534-8 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/ 9780226485348.001.0001

Illustrations in this book were funded in part or in whole by a grant from the SAH/Mellon Author Awards of the Society of Architectural Historians.

Support for the publication was provided by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

Names: Alexander, Zeynep elik, author.

Title: Kinaesthetic knowing : aesthetics, epistemology, modern design / Zeynep elik Alexander.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017008989 | ISBN 9780226485201 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226485348 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Aesthetics, German19th century. | Aesthetics, German20th century. | AestheticsPhysiological aspects. | AestheticsPsychological aspects. | Knowledge, Theory of. | Psychophysics. | Psychology and artGermany. | ArtStudy and teachingGermany. | DesignPhilosophy.

Classification: LCC BH221.G3 A44 2017 | DDC 701/.17dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017008989

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Anneme

Contents

A Peculiar Experiment

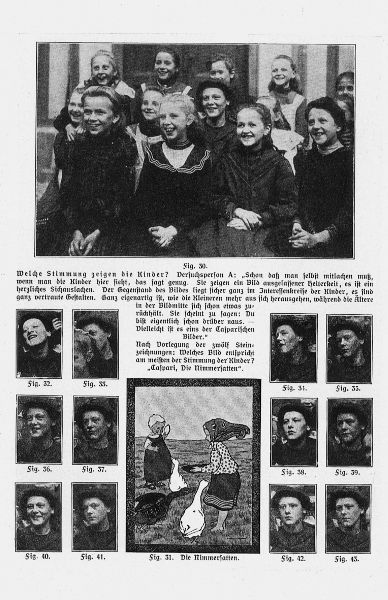

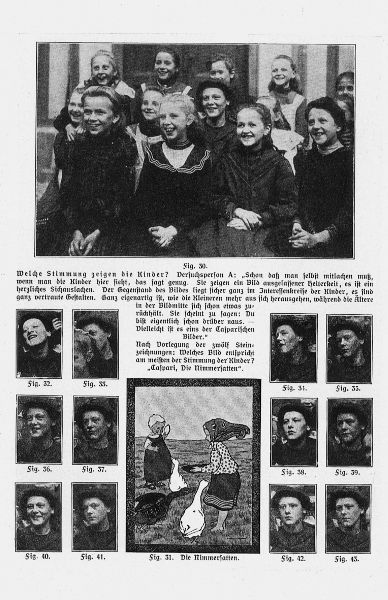

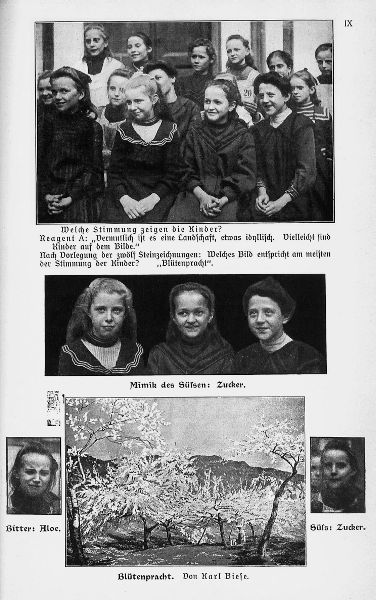

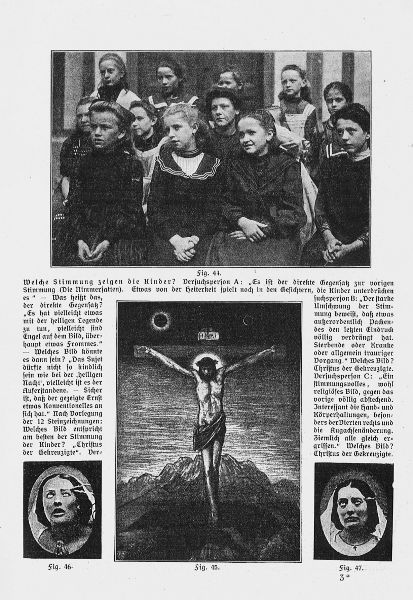

The following year Schulze published the results of the experiment (figs. If these subjects were in possession of an unconventional kind of intelligence, shouldnt the education system be changed to address it?

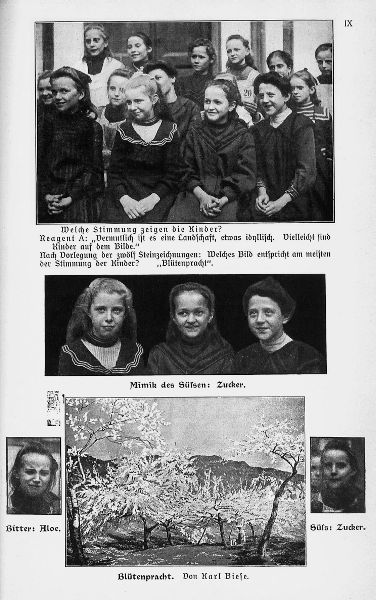

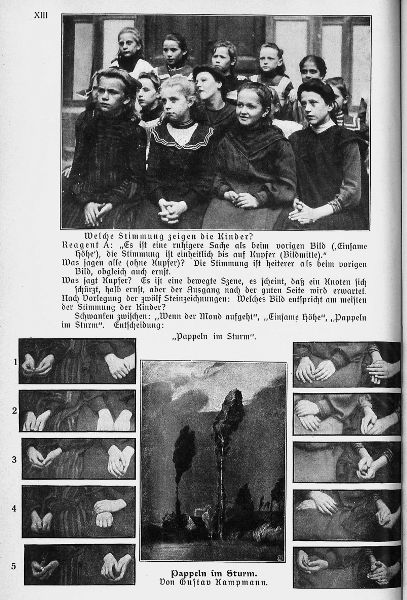

Figure 0.1. The group responds to the picture Storks. One girls response over time is illustrated in twelve additional photographs. Rudolf Schulze, Die Mimik der Kinder beim knstlerischen Genieen (Leipzig: R. Voigtlnder, 1906), 5.

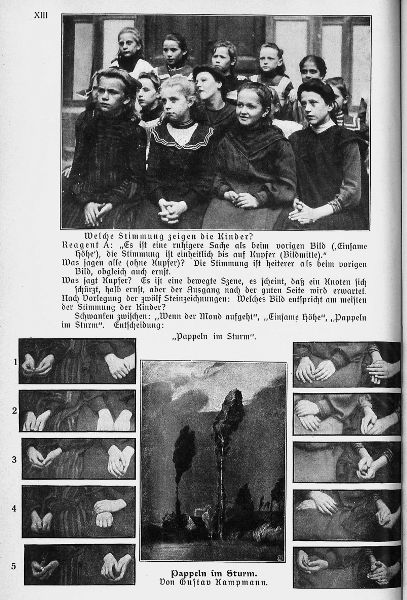

Figure 0.2. Girls respond to Poplars in the Storm. Their hand movements over time are illustrated in sequence. Rudolf Schulze, Die Mimik der Kinder beim knstlerischen Genieen (Leipzig: R. Voigtlnder, 1906), 30.

In analyzing the girls facial and bodily expressions, Schulze used a specialized terminology borrowed from experimental psychology. As the director of the Institut fr experimentelle Pdagogik und Psychologie (Institute for Experimental Pedagogy and Psychology), he had been instrumental in disseminating among fellow educators concepts, techniques, and equipment that had been developed within this relatively new field.

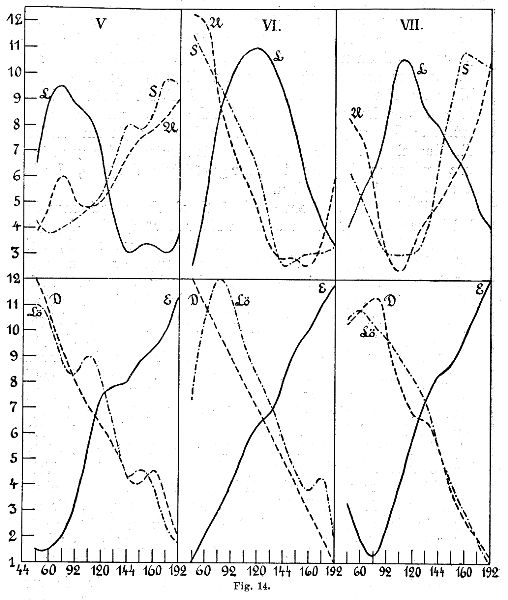

Schulze did not only borrow his methods and equipment from experimental psychology. His understanding of affective response conformed to the basic assumptions of a field upon which the discipline of experimental psychology itself had been founded in the previous century: psychophysics. As the name implies, psychophysics claimed that every sensation psychologically felt by the subject could be correlated quantitatively to a physical stimulus. Schulze had simply replaced Duchennes electrical current with forms.

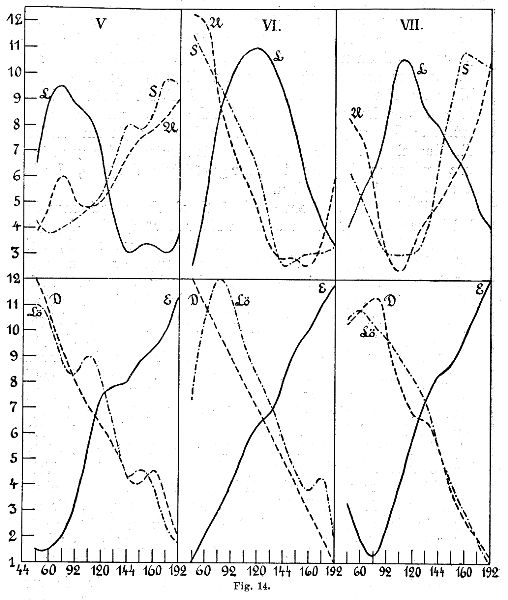

Figure 0.3. Diagram demonstrating the Wundtian tridimensional theory of feeling. The three curves in each section are pleasure-displeasure (Lust-Unlust), arousing-subduing (Erregung-Hemmung), and strain-relaxation (Spannung-Lsung). Alfred Lehmann, Die Hauptgesetze des menschlichen Gefhlslebens (Leipzig: O. R. Reisland, 1892), unpaginated.

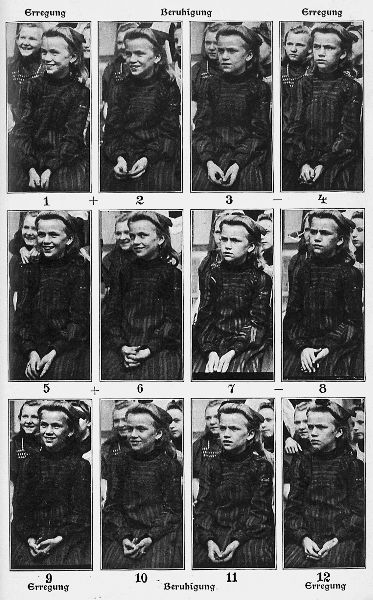

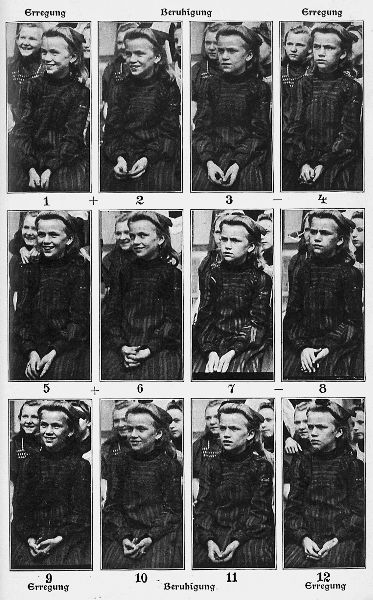

Figure 0.4. Facial expressions of one subject arranged along an x-axis of excitation and relaxation (Erregung-Beruhigung). Rudolf Schulze, Die Mimik der Kinder beim knstlerischen Genieen (Leipzig: R. Voigtlnder, 1906), 33.

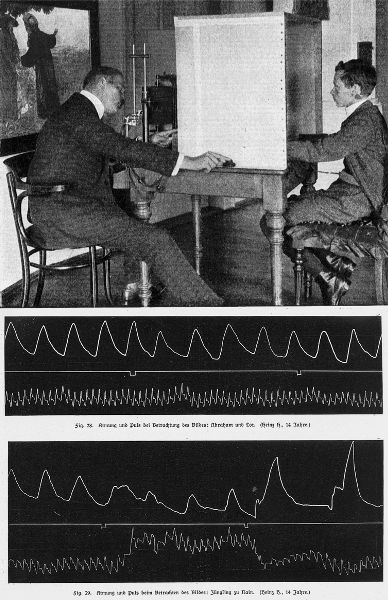

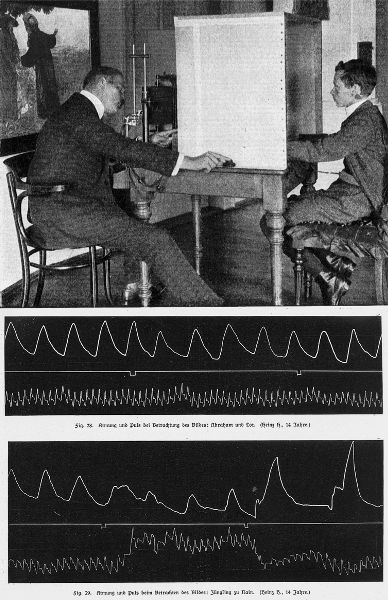

Figure 0.5. Experiment documenting the pulse and breathing of a child while he looks at pictures. Rudolf Schulze, Aus der Werkstatt der experimentellen Psychologie und Pdagogik (Leipzig: R. Voigtlnder, 1909), 84, fig. 68; 89, figs. 74, 75.

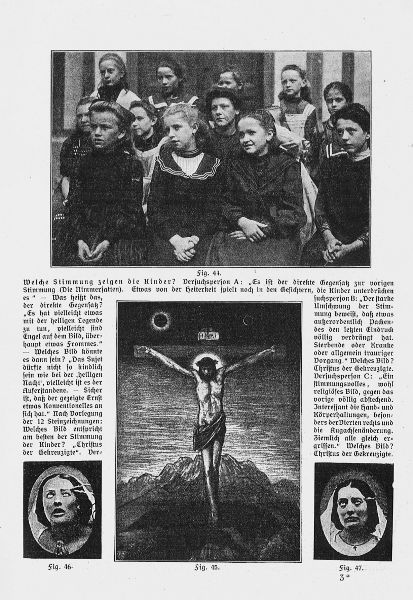

Figure 0.6. The girls response to Flowers is compared to their experience of sugar. Rudolf Schulze, Die Mimik der Kinder beim knstlerischen Genieen (Leipzig: R. Voigtlnder, 1906), 23.

Figure 0.7. The girls response to Crucifixion is compared to Duchenne de Boulognes experiments. Rudolf Schulze, Die Mimik der Kinder beim knstlerischen Genieen (Leipzig: R. Voigtlnder, 1906), 22.

As peculiar as Schulzes experiment may seem to us today, it would not have appeared so at the turn of the twentieth century. In fact, Schulzes contemporaries would have rightfully understood the experiment as an exercise in aesthetics from below (Aesthetik von unten). A term coined in the 1870s by Gustav Theodor Fechner, who, not coincidentally, was also the founder of the field of psychophysics, aesthetics from below purported to counter the philosophically inclined aesthetics from above (Aesthetik von oben).

Implicit in Schulzes peculiar experiment were questions that have a long history in Western intellectual life. Is all legitimate knowledge the product of thought? Or can the bodys physical exchanges with the world produce reliable knowledge without recourse to language, concepts, propositions, or representations? Once certain explanatory frameworks became entrenchedmind and body, object and subject, particular and universal, or cause and effectthe conundrum seemed inevitable. On the one hand, one Enlightenment thinker after another recognized in the presumed immediacy of experience another way of knowing. This was what A. G. Baumgarten, the eighteenth-century philosopher who gave the field of aesthetics its name, called

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).