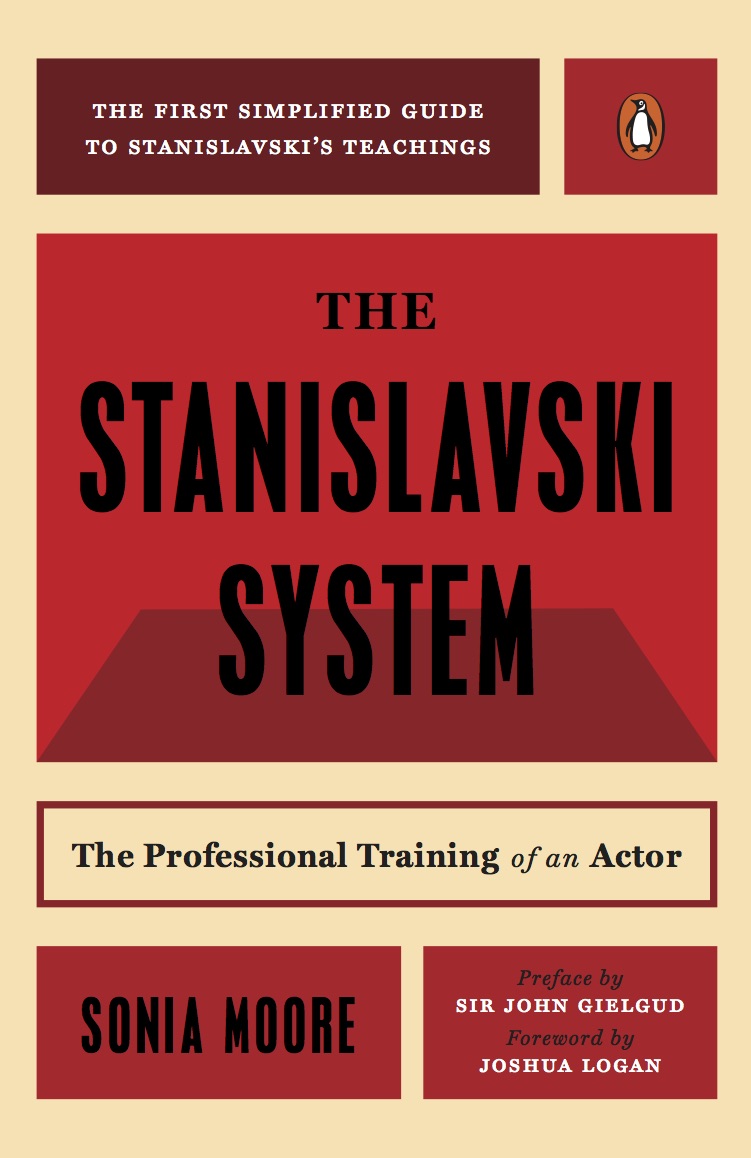

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE STANISLAVSKI SYSTEM

Sonia Moore (19021995) was born in Russia. She attended the universities of Kiev and Moscow, the Studio of the Kiev Solovstov Theater, and the Third Studio of the Moscow Art Theater, and earned degrees from conservatories in Rome. She lived for many years in New York City, where she taught at the Sonia Moore Stu- dio of the Theater and served as Artistic Director of AST of the American Center for Stanislavski Theater Art, which she founded. In addition, she taught and lectured at colleges and universities throughout the country.

Also by Sonia Moore

Training an Actor:

The Stanislavski System in Class

SECOND

REVISED

EDITION

T HE

S TANISLAVSKI

S YSTEM

The Professional Training of an Actor

DIGESTED FROM THE TEACHINGS OF

Konstantin S. Stanislavski

BY

Sonia Moore

(Originally published as The Stanislavski Method)

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

First published in the United States of America as The Stanislavski Method by Viking Penguin Inc. 1960

Published simultaneously in Canada

Published, with revisions, as The Stanislavski System 1965

The Stanislavski System, New Revised Edition, published in a hardbound and a paperbound edition 1974

Paperbound edition reprinted 1974, 1975, 1976

Published in Penguin Books 1976

Reprinted 1977, 1978, 1979, 1981 (twice), 1982, 1983

Second revised edition published 1984

Copyright 1960, 1965, 1974, 1984 by Sonia Moore

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Ebook ISBN 9781101562581

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Moore, Sonia.

The Stanislavski system.

[A Penguin handbook]

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Stanislavski method. I. Title.

PN2062.M61984792'.02884-2855

ISBN 9780140466607

Cover design: Christopher Sergio

Version_2

AUTHORS NOTE TO THE

SECOND REVISED EDITION

I t is my conviction that if the only existing systematized acting techniquethe results of Stanislavskis life workbecame the uniform method of training for actors in the United States, theater would achieve the high artistic level of the other arts in the United States. With the objective of bringing into this country Stanislavskis teachings and his ultimate technique, which is the solution to spontaneous behavior on stage, I am continuing to research the writings of Russian theater scholars and scientists who have been studying Stanislavskis overwhelming discovery.

This second revised edition includes the data of my latest researches. The emphasis is on intense sensitivity of the actors body to make it capable of the immediate expression of inner processes and of what words alone cannot project: the subtext of behavior on stage.

Sonia Moore

New York City, 1984

PREFACE

by Sir John Gielgud

I have never really believed that acting can be taught. Yet, when I remember what a clumsy beginner I was myself and how greatly I have been influenced, all through my long stage career, by the fine directors and players with whom I have been fortunate enough to be associated, I cannot deny the advantage of teaching, provided it can be followed up by hard personal experience. Let nobody imagine, however, that he can learn to act from reading books, however intelligent or profound they may be, about the art of acting.

All creative art can be studied, of course. When one is young, one imitates the players one most admiresas artists copy great pictures in the galleries. But, as the theater is an imitation of life, it is as ephemeral and intangible as life itself (in a way that music, painting, and literature are not), and it changes in every decade and generation. One cannot copy acting, or even what seems to be the method of acting. One has to experiment and discover ones own way of expression for oneself, and one never ceases to be dissatisfied. The quality and development of ones work changes with the degree of responsiveness and sureness of technique which one has acquired over the years. One is affected, too, by the style and quality of the work in hand, the respect or dissatisfaction one may have with ones material, and by ones own personal reactions to directors and fellow players, to the author, to the play itself.

There are so many lessons in the theater to be learned: application, concentration, self-discipline, the use of the voice and body, imagination, observation, simplification, self-criticism. Often the tradition of the theater seems to be at odds with the modern expression of original contemporary acting. I believe that one is as important as the other and that one should study and learn from both. Ones basic technical equipment should be perfected in order to enable one to relax, to simplify, to cut away dead wood.

Just as one moves, in real life, from one phase to another, experiencing almost imperceptible developments along the road as one gets older and ones personal and professional experiences lead one to make new discoveries about oneself and life in general, so it is hard to pin down on paper any practical guide to help an individual actor to select the best means of discovering the wellsprings of his arthow he can draw from his own sensitivity the power to command an audience and fascinate them by his interpretation of emotions given him in a particular form by the playwright and presented by him with the guidance of the director. Since he is not the sole creator, but only an instrument working in an uncertain medium (gloriously flexible yet desperately fallible), he needs all the more to have his physical and vocal means under strict control. He must think about his work in the many hours when he is not actually practicing it, about how to cherish his powers of imagination so that he can summon them at will just at the time he needs them. He has to perform before a living audience eight times a week, after achieving a more or less finished performance in the three or four short weeks at his disposal for rehearsal, working perhaps with a director and actors with whom he may not be in sympathy. Even before this he may have had to convince a director, in a few short minutes, that he is competent to play a role for which many others are also being considered.