JEWISH QUESTIONS

JEWISH QUESTIONS

RESPONSA ON SEPHARDIC LIFE

IN THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD

Matt Goldish

Copyright 2008 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Goldish, Matt.

Jewish questions : responsa on Sephardic life in the

early modern period / Matt Goldish.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-12264-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-691-12265-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. JewsTurkeyHistorySources. 2. SephardimTurkey

HistorySources. 3. TurkeyHistoryOttoman Empire, 12881918

Sources. 4. TurkeyEthnic relationsSources. I. Title.

DS135.T8G58 2008

305.89240560903dc22 2007047195

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

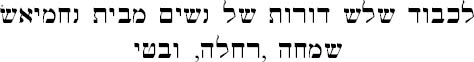

This book is dedicated to three generations of great women from the

Nahmias family, one of the most illustrious clans in Sephardic history:

Simhah Nahmias, Rahel Nahmias, and Betty Goldish.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Responsa are collections of questions on Jewish law asked by individuals or groups, and the responses given by rabbis. The genre has existed for well over a thousand years, and it has been used by historians almost since the inception of modern Jewish historiography. Much of the responsa literature has been easily available in print for a long time, and is now available in electronic form as well. At the same time, the responsa are one of many sources shedding light on the history of the Sephardic Jews, the group with which the present volume is concerned. There are Ottoman and European court records, travelers diaries, municipal records, Hebrew books of all genres, personal correspondence, and more. Several good histories of the Sephardim are already available. What, then, makes this book different and useful?

One answer is that the book includes texts that are usually available only to the Hebrew reader who knows where to look and how to understand specialized legal terminology. This material throws light on every aspect of post-Expulsion Sephardic life, but it also opens vistas into Jewish social, economic, religious, and political history in the early modern era. Even seasoned historians may well discover something new in these documents.

The book has another, more novel goal as well. In the past, historians have generally used responsa in the pursuit of specific historiographic goals reflecting the scholarly concerns of each generation. These texts have been a basis for the study of Jewish communal structures, community histories, rabbinic biographies, histories of specific laws and their application, and, more recently, topics in social history, such as the position of women, gays, converts, and other groups in Jewish society.

Whoever constructed or edited the questions into their current form was constrained to configure ephemeral life experiences into a coherent tale. In some cases the result is a dry, terse Hebrew legal style, but often the story should be recognized as a piece of literature in itself. The authors searched biblical and rabbinic language for expressions that capture both the events under discussion and their emotional impact. Sometimes this exercise is quite creative. If we tune in to the rhythm of lived Jewish experience, we can hear the voices of the past telling their tales in the responsa. Though the texts that have reached us are usually edited, they remain remarkable for their preservation of life stories.

I focus on the Jewish exiles from Spain and Portugal and their progeny, so my sources are limited to Sephardic material from the early modern period (late fifteenth century to middle eighteenth century). If a story was interesting but told little about the specifically Sephardic experience, I might have passed it by, but this was seldom the case. Every tale gives details about life in one or more Sephardic communities. These particulars are woven together into a tapestry of Sephardic life that can only be perceived when the narrative portion of a document is read as a whole.

While I do not completely avoid the very best known collections, I have generally preferred the responsa of figures less familiar today. The type of material in all these collections is substantially the same, but historians have mined the famous works to the extent that these cases may be familiar. The lesser known collections, containing equally interesting cases, often languish in obscurityespecially those from rabbis outside the largest cities.

The parameters of the world I treat in this book may not be the same as those chosen by other historians of the Sephardim. The entire question By the end of the conference it was clear that no terminology remains untainted by questions and qualifications.

My essential criterion for the Sephardic diaspora is linguistic. Any country or community where Spanish or Portuguese in some form was generally used by Jews, either for everyday speech, business purposes, or religious discourse, is included in the Sephardic world for this book. Occasionally, however, I impinge on areas (particularly in Morocco) where Spanish was far from the main spoken language among local Jews.

The Sephardim who left Spain and Portugal usually made their way to existing Jewish communities that were predominantly non-Sephardic. In the Ottoman Empire and much of North Africa, despite a good bit of resistance, Sephardic culture, language, and traditions overshadowed the older, local ones after a time. The leading place of Sephardim in trade made Spanish the necessary language for Jewish merchants in the whole region. Thus, our material involves a number of individuals who were not technically Sephardim but who lived in this Sephardic milieu. On the other hand, the book does not incorporate responsa from Persia, Yemen, or other Eastern Jewish communities that did not absorb major influxes of Iberian exiles. A second issue is my inclusion of the Western Sephardim of Amsterdam, London, Hamburg, Livorno, and southern France. As I explain below, these communities were made up of escaped conversos and were different from the rest of the Sephardic world in many ways. Nevertheless, they considered themselves Sephardic congregations and their languages were Spanish and Portuguese. The documents show that some important cultural and religious commonalities appear along the same lines as my linguistic borders.

Next page