Table of Contents

FOR KATU

OVERVIEW

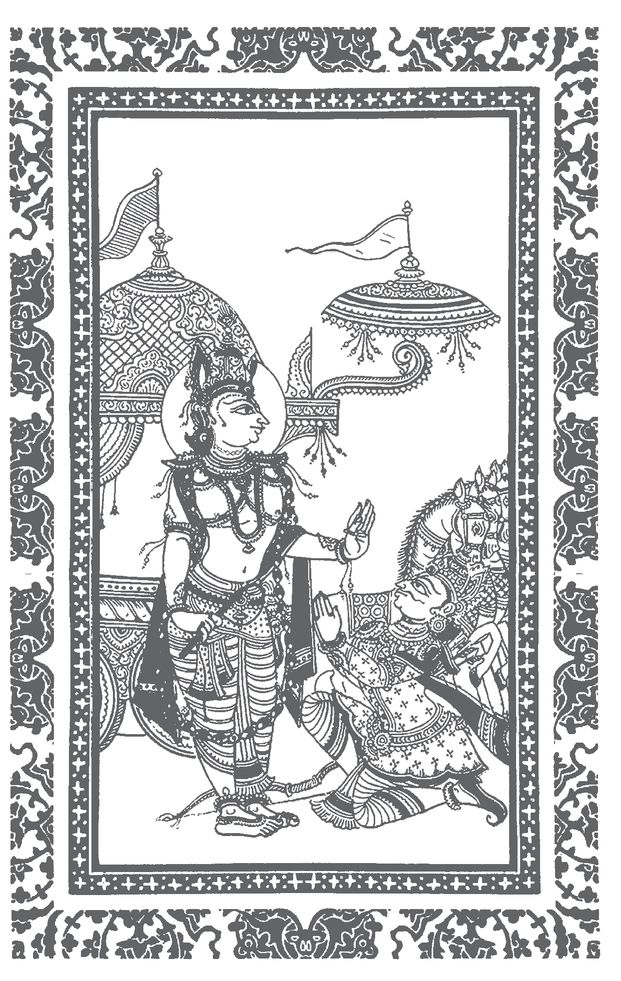

It is dawn, just before the start of an epic war. Two armies comprising nearly four million soldiers fill a vast battlefield. Warrior elephants, their armored tusks glistening in the sunlight, trumpet and stomp the ground. Horses tethered to gold-plated chariots pull at their reins, anxious for the attack. Soldiers beat drums, rattle spears, ready bows and arrows. Between the two armies, noble prince Arjuna looks out from his chariot and envisions the destruction to come. This war is a last chance for his family to regain the kingdom stolen from them fourteen years before by ruthless cousins. Yet, in these final moments, he falters. He turns to his friend and mentor Krishna, who serves as Arjunas charioteer, and confesses to feelings of horror over the lives that will be lost and shame over his participation. What follows is a two-hour dialogue, known as the Bhagavad Gita, or Song of the Supreme Person, one of the worlds most renowned testimonies to the transformative power of love.

No voice recording exists of the conversation between Krishna and Arjuna. No audio file reveals which words were emphasized or delivered with greatest passion. No visual record survives to indicate facial expressions, gestures, body language, or other nonverbal indicators of intent and meaning. We are adrift in their discussion, charting our course by the celestial commentaries of wise yogis and learned devotees At the Gitas core, they declare, is this message: We have wandered away from our eternal self. Through practice of bhakti, the yoga of devotion, we can recover our lost identity as eternal beings and reawaken the love dormant in our souls. This, the Gita says, is the ultimate purpose of yoga and the fulfillment of the human mission.

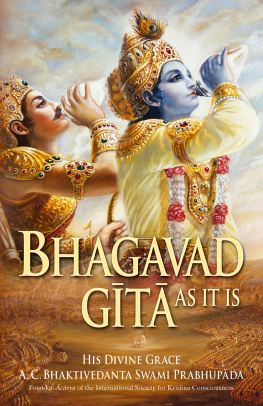

One devotee-scholar who dedicated his life to propagating this core message of the Gita was my teacher, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (18961977). Prabhupada wrote an elaborate and well-known commentary titled Bhagavad Gita As It Is, but he believed that the Gita deserved the widest possible exposure and encouraged his students to publish their own realizations. What follows is an attempt to honor that mandate.

As with anything profound and beautiful, understanding of the Gita matures with time. When I began my bhakti studies at age nineteen, the Gitas warning about kama or cravings meant sex and food to me. Since then I have seen that intellectual pursuit, artistic expression, or scientific inquiry can also constitute a craving if it feeds pride and isolates us from our eternal self. When I was in my twenties ahankara or ego meant an independence which needed to be sublimated. Forty years later, I know the dangers of sublimation and can respect a healthy ego, one that is self-assured without being arrogant. Some of these modest realizations appear here in the form of footnotes. Since this book is also intended to familiarize readers with many of the Gitas main concepts and terms, these have been indicated in italics upon their first appearance in the text. The most prevalent of these are explained in the chapter titled Topics in the Gita.

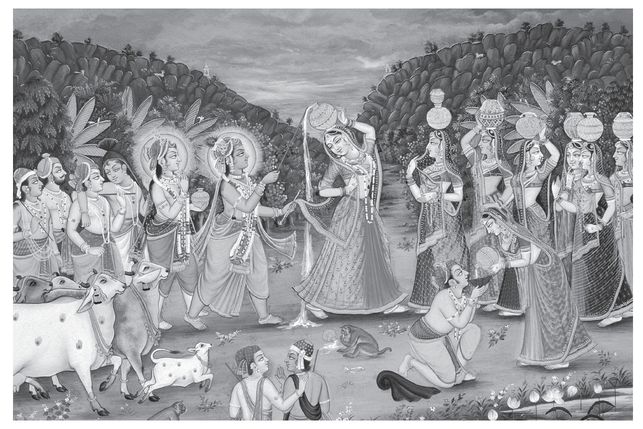

Krishna with the gopis of Vraj.

The word Bhagavad in the title refers to Krishna, a name used in Indias bhakti texts to indicate God in personal form. Within the context of the Gita, God and Krishna are basically the same, with one important distinction: God refers to the Supreme Being with reference to a creative function, while Krishna refers to the individual behind that creative functiona unique individual possessing a beautiful form and loving demeanor. The name Krishna translates as most attractive, and for thousands of years Krishnas attractive, loving nature has inspired expressions of devotion in art, poetry, music, and dance. Bhakti scholars describe the souls yearning to love God as occuring in progressive stages called

rasas, or tastes, rising from a passive awareness to servitude, friendship, parental affection and, in its most intense form, a mood of conjugal intimacy. The Bhagavata Purana offers a description of this love for the Supreme in its highest stage:

Hearing the sweet music of Krishnas flute the hearts of the gopis [cowherd women] melted, their passion swelled, and with earrings swinging wildly they ran to the place where their beloved waited. He is the Supreme Soul, but they knew him only as their lover. He is imperishable, the origin of creation, yet he appears in the world to receive the love of his devotees. The gopis said, O dear one, please quench the fire burning in our hearts with the nectar of your lips. Who in all the worlds would not abandon everything for you? Even animals, trees, birds and cows are elated seeing your beauty....

The Bhagavata says that this Krishna who plays sweet music and attracts the hearts of all souls is the ultimate object of love. In the Gita he fulfills a more sober role, that of Supreme Person appearing in the world to reestablish dharma, or the path of righteousness. Starting in the 1700s when they entered India, British educators and missionaries differentiated these two sides of Krishnas personality for reasons we will explore later. Yet to achieve a clear understanding of the Gita, readers should remember that Krishna the beloved of all souls and Krishna the Supreme Being and upholder of dharma are one and the same individual.

According to Gita theology, all souls emanate from the Supreme Being and share his loving nature, as sparks emanating from a fire share in minute degree the fires heat and light. This includes the Supreme Beings independence. Love implies possessing the independence to not love, and some souls leave their relationship with the Supreme Being to experience life apart in the material world. Over countless births, layers of psychic conditioning cover remembrance of their original nature and the hearts of these forgetful or conditioned souls grow hard. Krishnas purpose in speaking the Gita was to reveal how hard hearts can be softened through bhakti. Because the Gita touches on many topics, the majority of commentaries (there are more than 400 in English alone) miss this message of love in their philosophical and religious analyses, yet it is the core of the Gitas instruction.

Not everyone confronts enemies on a literal battlefield as Arjuna does in the Gita; still, the Gita poses questions which challenge us all: Who are we? Where do we come from? Why we are here? And, as with all great literature, the more we study the Gitas main characters, the more they resonate with emotions we can understand. Krishna and Arjuna played together as children. They were close friends in youth and became family when Arjuna married Krishnas sister. We learn from other bhakti texts that later in life they shared extraordinary adventures, including a journey through subtle pathways to places outside the known universe. Plainly put, Indias most revered scripture is a heart-to-heart talk between two people bound together by friendship and love.