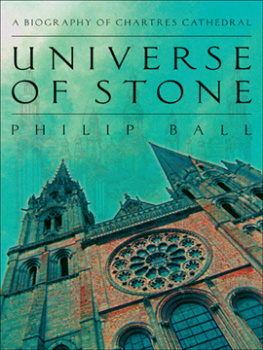

It is always salutary to be reminded why writers need good editors, and both the shape and the fine print of this book have benefited immensely from the advice and experience of Will Sulkin and Terry Karten, whose enthusiasm has been a sustaining force. My agent Clare Alexander has also provided plenty of the latter, as has my wife Julia, with whom I discovered the delights of Chartres at first hand. Caroline Jackson generously read the section on medieval glass, and Donald Royce-Roll supplied some valuable papers on that topic. Alex Rowbotham has provided splendid images of the cathedral that I might not otherwise have had the means to obtain.

In 1204 some of the finest churches in Christendom were ransacked and the precious icons and relics were divided up among the plunderers. They snatched reliquaries from altars, forced open chests filled with holy treasures, stripped gold and silver metalwork from church fixtures. In their haste they spilled the sacramental wine over the marble floor, where it might mingle with the blood of any priest who stood in their way.

But these marauders were not infidels. They were Christian knights of the West, the flower of Europes chivalry, bearing the sign of the cross that identified them as Crusaders. For this expedition, the Fourth Crusade, went not to the Holy Land and Jerusalem but to Constantinople, the capital of the eastern Holy Roman Empire, where the schismatic Greek rulers refused to recognize the authority of Pope Innocent III.

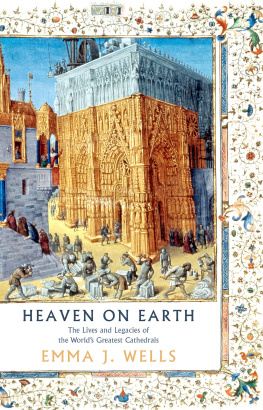

This was not the only crusade underway at that time. There was another afoot in Europe itself, and it was concerned not with sacking churches but with building them. Just as the knights of France, England and Germany were despoiling the gilded splendour of the Hagia Sophia, builders in their homelands were inventing a new architectural style that would rival the glories of Byzantium. Over some three hundred years, the Europeans engaged on a cathedrals crusade, building churches on a scale never again equalled either in size or in quantity. In France alone, eighty cathedrals, five hundred large churches and several thousand small churches were constructed between 1050 and 1350. At the end of this period there was, on average, a church for every two hundred inhabitants of France and England.

And these were not squat and gloomy edifices in the style we now know as Romanesque, but towering monuments of stone and glass, filled with light and seeming to ascend weightlessly towards heaven. They were the Gothic cathedrals. Now considered the finest works of medieval art, these churches are even more than that. They represent a shift in the way the western world thought about God, the universe and humankinds place within it.

The Gothic Myth

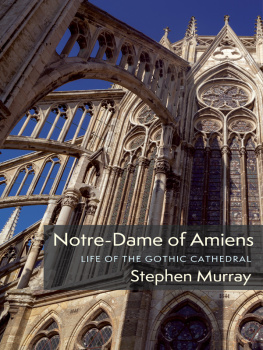

Our contemporary view of that transformation is obscured by a lot of rubble. Much of it was deposited in the nineteenth century, whose historians, artists and architects, in the course of rescuing the Gothic style from ill repute, laid down a mythology about what it represents. When we think of a cathedral today, it is a Gothic building that comes to mind, not the heavy Romanesque precursors. And for many of us this vision is embodied in a specific edifice, standing in what has been rightly called splendid isolation on the le-de-la-Cit: Notre-Dame de Paris, immortalized by Victor Hugo in his eponymous novel of 1831.

Hugos book wasnt simply a work of fictionit was a meditation on architecture in general, and on the architecture of the Gothic age in particular, and it defined a vision of these things in the same way that Dickens described a version of London that has now become inseparable from that citys stones. For Hugo, the Gothic cathedral was a social construction, a temple made for and by the people rather than decreed by an ecclesiastical elite. That image chimed very much with the tenor of post-Revolutionary France, and it gave rise to a myth of the cathedral that is still pervasive today. The greatest works of architecture, said Hugo,

are not so much individual as social creations; they are better seen as the giving birth of peoples in labour than as the gushing stream of genius. Such works should be regarded as the deposit left by a nation, as the accumulations of the centuries, as the residue of successive evaporations of human society, briefly, as a kind of geological formation.

Its not just Hugos exquisite prose that makes the idea seductive. We can feel a little less overwhelmed by the stupendous scale and structure of the cathedrals of Notre-Dame de Paris, Strasbourg and Chartres, if we can indeed regard these buildings as something geological, created by the immensity of time and the energy of countless generations, rather than as objects that were conceived in the minds of a handful of men and constructed by labourers stone by stone. And we need not feel oppressed by their colossal size if, like Hugo, we believe that in the Gothic era the book of architecture no longer belonged to the priesthood, to religion or to Rome, but to the imagination, to poetry and to the people.

Hugo was not the first to voice these views, but no one had previously found words so compelling, and he made them so familiar that a whole generation of French intellectuals, historians and artists fell under their spell. For Eugne Viollet-le-Duc, the great nineteenth-century restorer of French Gothic buildings, Hugos reading of the Gothic cathedrals meant that they became national monuments and a symbol of French unity. If this belief helped Viollet-le-Duc return some of Frances great churches to a state approaching their former glory, we have reason to be grateful for it. But that does not make it any less a facet of the romantic myth of the cathedral.

It is hardly surprising that historians of 150 years ago needed to have some story to weave around the Gothic cathedrals. These monuments seem to sit in defiance of the traditional narrative we have spun about western history, in which the Middle Ages separate the wonders of Greece and Rome from the genius of the Renaissance with an era of muddle-headed buffoonery. We are even now apt to forget that it was the Renaissance historians themselves who constructed this framework. Today, however, there is no shortage of alternative stories to replace that created by Hugo and his contemporariesand each tells us something about our own times, regardless of how much light they shed on the High Middle Ages. And so the cathedrals become cryptograms of ancient, sacred knowledge; or they are symbols of church oppression; or they are testaments to the skills of the medieval engineers. Many of these stories have some truth in them; none gives us the full picture. That, after all, is what all great works of art are like: they are never unlocked by a secret code, but they may be enriched by repeated viewing, first from this angle, then from that. Knowing how and why they were created does not allow us to understand them fully, but it may inspire us to love them more ardently.