CONTENTS

Guide

Victor A. Pollak has practiced as a business lawyer since 1976 with law firms in Chicago and Salt Lake City before turning to writing. He holds a BA from Antioch College, a JD Cum Laude from Loyola University of Chicago School of Law, and an MFA in writing from Pacific University. He divides his time between Tucson and Salt Lake City.

Published by Stackpole Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

800-462-6420

Copyright 2020 by Victor A. Pollak

Maps created by Mary Lee Eggart

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Names: Pollak, Victor A., 1948 author.

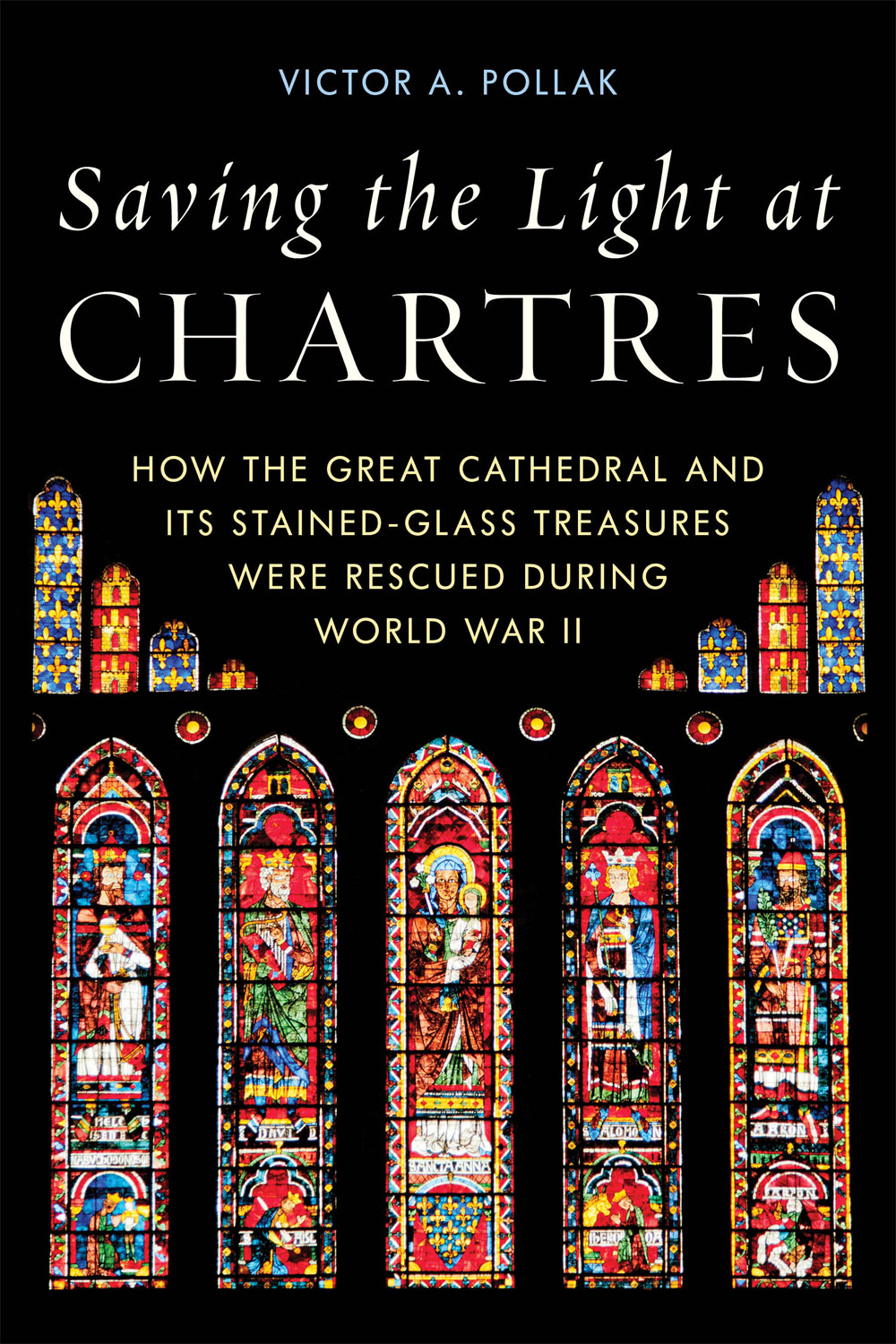

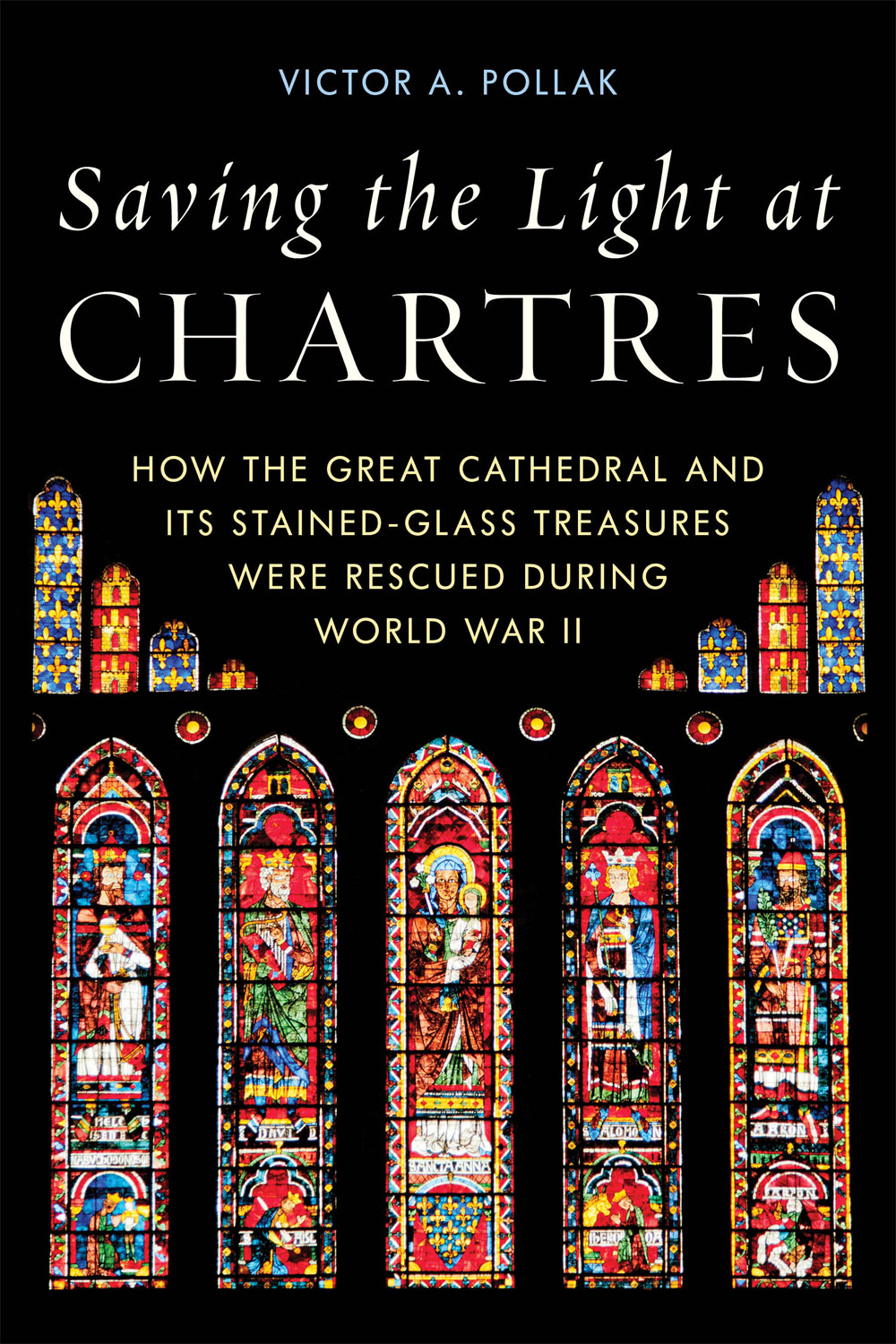

Title: Saving the light at Chartres : how the great cathedral and its stained-glass treasures were rescued during World War II / Victor A. Pollak.

Description: Guilford, Connecticut : Stackpole Books, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: The cathedral at Chartres survived World War II thanks to the efforts of French citizens and an unrecognized American officer. In a book written in the spirit of The Monuments Men , Victor Pollak describes the efforts to save Chartres CathedralProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019038528 (print) | LCCN 2019038529 (ebook) | ISBN 9780811739016 (cloth) | ISBN 9780811768979 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Stained glass windowsFranceChartres. | Cathdrale de Chartres. | Art treasures in warFranceChartresHistory20th century. | Cultural propertyProtectionFranceChartresHistory20th century. | Griffith, Welborn Barton, 19011944.

Classification: LCC NK5349.C5 P65 2020 (print) | LCC NK5349.C5 (ebook) | DDC 748.50944/51240904dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019038528

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019038529

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

For Elizabeth Russell Pollak

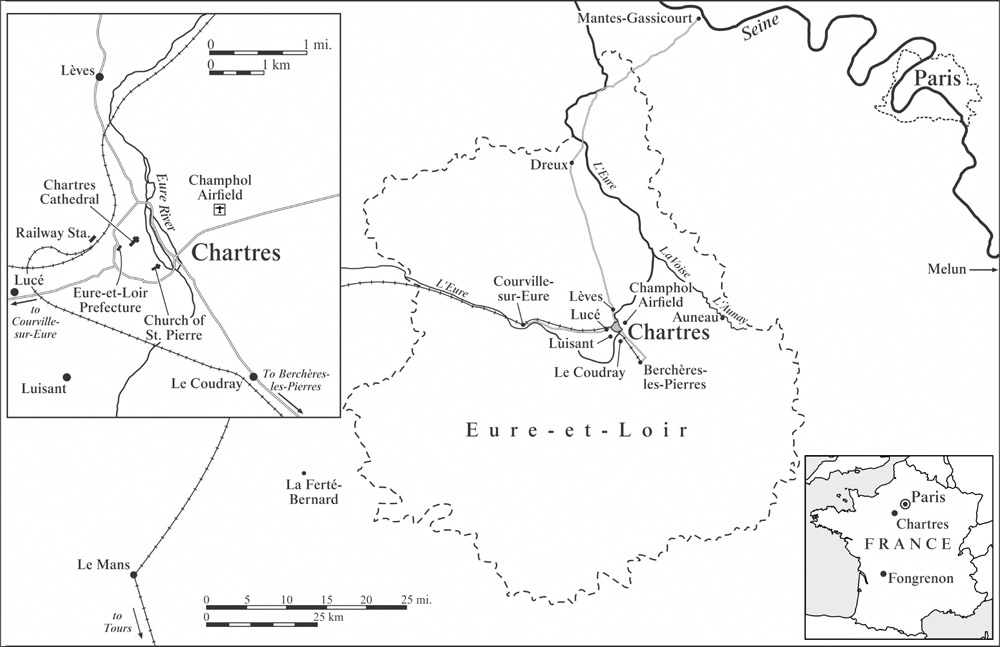

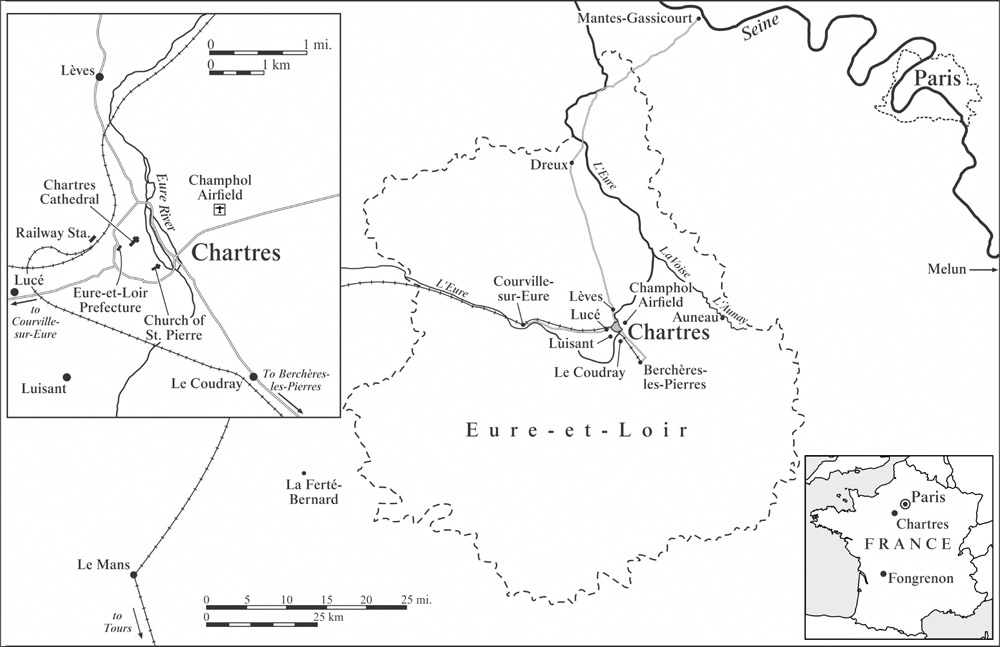

Chartres and Vicinity

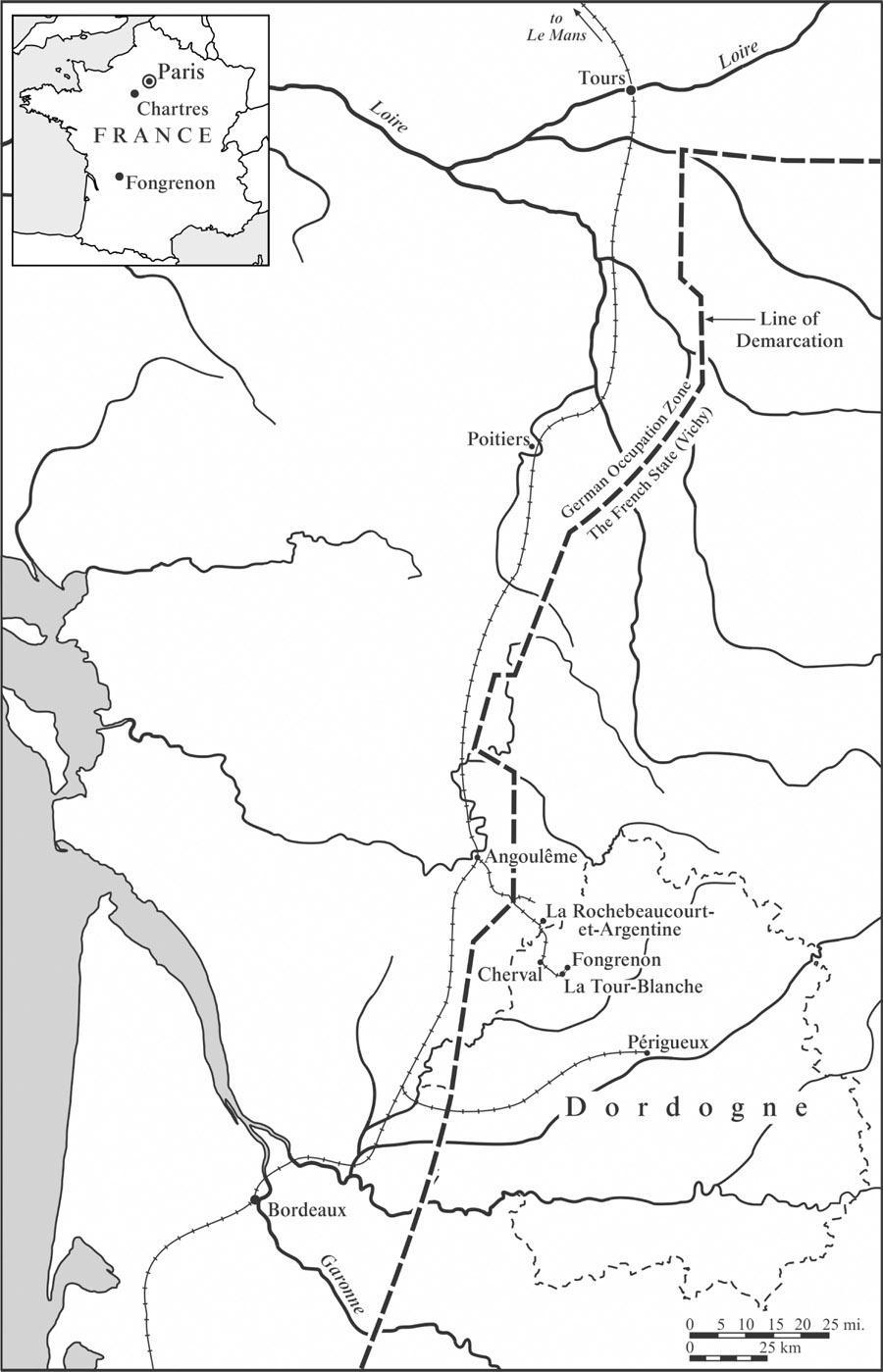

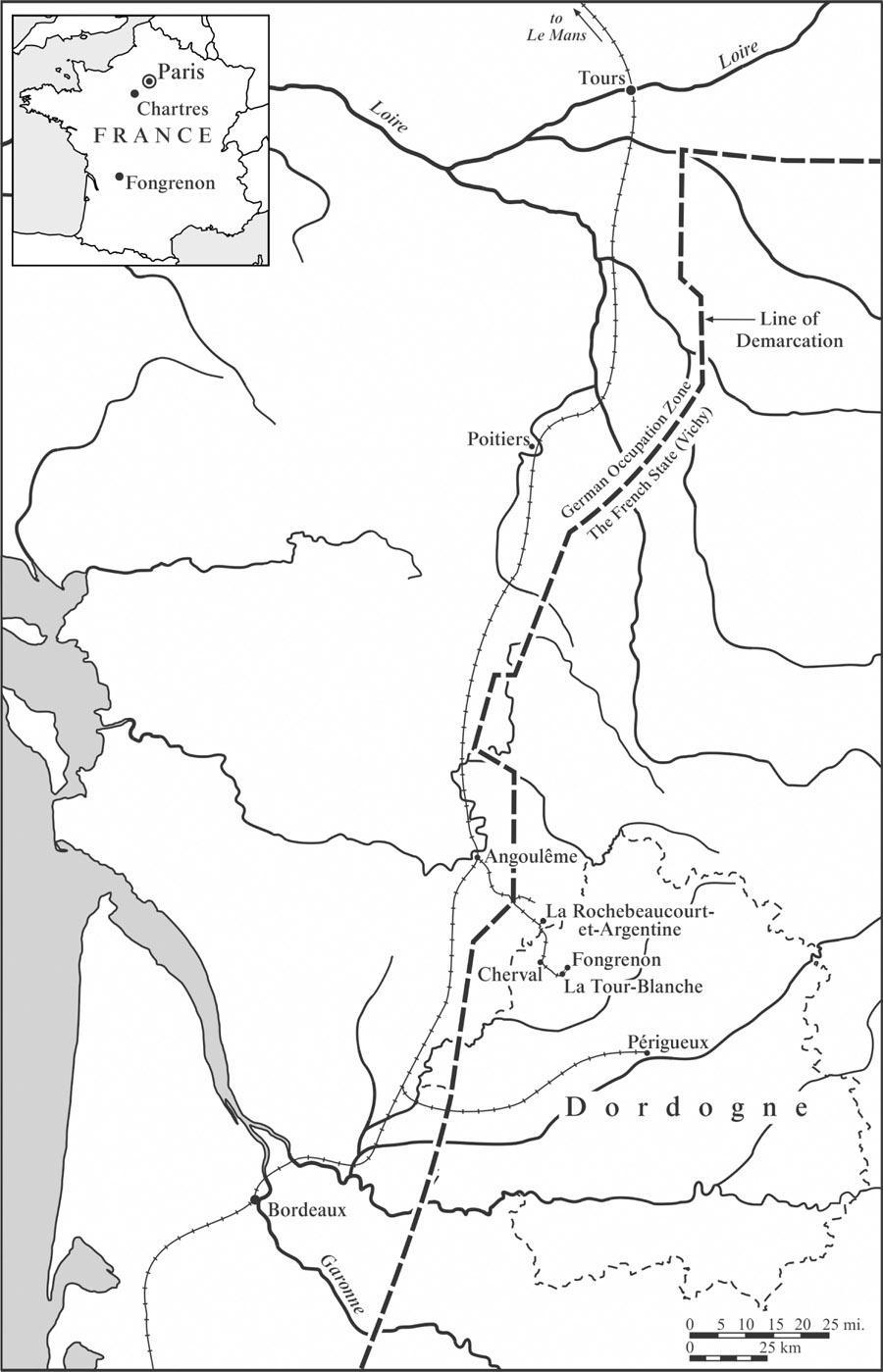

Western Dordogne and Fongrenon Castle (Chteau de Fongrenon)

IN MAY 2013, MY WIFE AND I DROVE A GOOD PORTION OF THE ROUTE of what would be that years Tour de France, its hundredth running, taking a path through a countryside abundant with landmarks of historical significance to the race, to France, and to the world: Nice, Marseilles, Ax 3 Domaines, Saint-Malo, Mont-Saint-Michel, Lyon, Mont Ventoux, Alpe dHuez, and of course the fabled cobbles of the Champs-lyses in Paris. There was so much to see in this beautiful country, so many treasures like the Bayeux Tapestry, chteaus and vineyards and mountains and cathedralsall of them jewels to our eyesbut something in Paris struck me as particularly poignant: I remember standing inside Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, with its medieval stained-glass windows that transformed daylight into lilac. We were bathed in majesty and from this feeling coming to a profound understanding: a cultural monumenta cathedral, a statue, a bicycle raceis a jewel for the world to keep and to cherish for as long as humans live on this earth.

A year later, I was in my living room watching a CNN newscast when crackles of an explosion resounded from my TV. A stone building erupted in the Iraqi desert from a bomb blast deep in the ground, sending a shock wave of black-gray dust and smoke over a dry field. Cannonballs of sandstone fragmented in all directions. The voice-over reporter spoke: More than three thousand years of history obliterated in seconds. This video was released by ISIS. CNN cannot independently verify its authenticity, but it purports to show the radicals destroying Nimrud, one of the most important archaeological sites in Iraq.

In the video, I saw a bearded youth wielding a sledgehammer and smashing it into a stone wall covered with relief carvings. Pieces fell to the floor. He struck again and shoved it off the wall. It crashed onto the stone floor and scattered fist-sized chunks and dust.

Another man on a ladder swung a hammer and severed a white plaster sculpture from a wall. It was a mans face, flat and round, with prominent forehead, Roman hair, and dark holes for eyes, which looked straight forward, almost smiling. When the blow struck, the eyes looked down despondently, while the face ripped loose and crashed to the ground, breaking into chips and dust.

Again, the voice-over: These are remnants of the ancient Assyrian civilization. Nimrud used to be its capital. Theyve stood since the thirteenth-century BC and survived many wars but were destroyed by the militantsprobably in less than a day.

ISIS had posted this video within weeks of the destruction.

The following year, in the public square under the ancient Arch of Triumph in Palmyra, in Syria, built in the second millennium BC, ISIS publicly beheaded Khaled al-Asaad, a university professor and Palmyras general manager for museums. He had spent his life preserving antiquities. His crime, according to a Syrian official, was refusing to pledge allegiance to ISIS and refusing... to reveal the location of archaeological treasures and two chests of gold that ISIS thought were in the city.

ISIS claimed that it destroyed the antiquities out of religious duty, but its real motivation was purely financial and hypocritical: looting archaeological sites to support its thriving illegal trade in antiquities. When I saw the CNN video, a sense of loss and anger welled up inside me. Elise Blackwell wrote, It is a tragedy when human gifts that have survived across generations are disrespected for any reason short of basic survival. To loot artifacts for spending moneyor to allow that to happenis a violation of history.

Around the same time, Id also been listening to some lectures about great cathedrals, including Saint-Denis, Notre-Dame de Paris, Reims and Rouen Cathedrals, and Notre-Dame de Chartres. In World War II, the lecturer noted, Chartres stained-glass windows had been removed and hidden in the countryside to protect them from war damage.

I was amazed. I wondered how a project of such magnitude could be accomplished. I imagined scores of French workers in 1939, under threat of German invasion, working through the nighthoisting cranes, scaffolding, cables, and packing cases from trucks into the cathedral, and then craftsmen dismantling and removing thousands of glass pieces to be packed and transported. Where did they hide them? Who planned the project, and who did the work?

Unconnected in space and loosely connected in time, these three experiences are how this book started.

Over the years, Id heard of cultural monuments and artworks under attack during World War II. Yet hearing of Chartres in the wake of seeing that ISIS video propelled me to learn more about whats been done in the past to protect cultural treasures. How have people prepared to avoid such destruction and looting?

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.