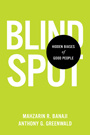

Copyright 2013 by Mahzarin R. Banaji and Anthony G. Greenwald

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Delacorte Press,

an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

DELACORTE PRESS is a registered trademark

of Random House, Inc., and the colophon

is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Excerpt from Billions of Bugs by Rick Walton from

What to Do When a Bug Climbs in Your Mouth.

Text copyright 1995 by Rick Walton. Used with permission of

the Author and BookStop Literary Agency. All rights reserved.

The lines from Midnight Salvage. Copyright 2002, 1999 by

Adrienne Rich, from The Fact of a Doorframe:

Selected Poems 19502001 by Adrienne Rich.

Used by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

The Sneetches, from The Sneetches and Other Stories by Dr. Seuss,

Trademark and copyright by Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. 1961,

copyright renewed 1989. Used by permission of Random House

Childrens Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Banaji, Mahzarin R.

Blindspot: hidden biases of good people / Mahzarin R. Banaji

and Anthony G. Greenwald

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-553-80464-5ISBN 978-0-440-42329-4 (eBook)

1. Prejudices. 2. DiscriminationPsychological aspects.

I. Greenwald, Anthony G. II. Title.

BF575.P9B25 2013

155.92dc23 2012015905

Book design by Susan Turner

www.bantamdell.com

v3.1

The sailor cannot see the North

but knows the Needle can

E MILY D ICKINSON , in a letter

to a mentor, T. W. Higginson, seeking an

honest evaluation of her talent (1862)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

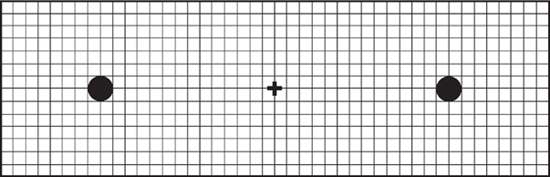

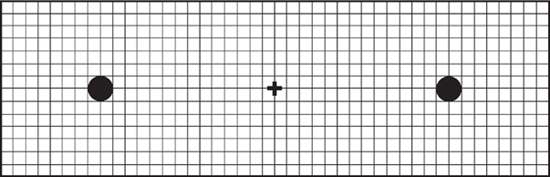

Like all vertebrates, you have a blind spot in the retina of each eye. This region, a scotoma (from the Greek word for darkness), has no light-sensitive cells and therefore light arriving at that spot has no path to the visual areas of your brain.

Paradoxically, you can see your own blind spot. Try it by looking with one eye at the plus sign in the middle of the rectangle on the opposite page. Cover the other eye with one hand and hold the page at arms length in front of you, then slowly bring the rectangle closer while maintaining your focus on the plus sign. When the page is about six inches away, the black disc on the same side as your open eye will disappear. It will reappear as you bring the page closer still. The moment of disappearance tells you when light from that disc is falling on the blind spot of your open eye. Heres a bonus: If you shift the gaze of your open eye to the still-visible disc on the other side, the plus sign will disappear!

You may have noticed something strange in the location of the vanished disc. When it disappeared, it left no blank spotno hole in the grid background. You saw an unbroken grid. Your brain did something quite remarkableit filled in the blind spot with something that made reasonable sensea continuation of the same grid that was visible everywhere else in the rectangle.

A much more dramatic form of blindness than the one you just experienced occurs in a pathological condition called blindsight, which involves damage to the brains visual cortex. Patients with this damage show the striking behavior of accurately reaching for and grasping an object placed in front of them, even while having no conscious visual experience of the object. If you place a hammer before the patient and ask, Do you see something in front of you? the patient will answer, No, I dont. But ask the patient to reach for and grasp the hammer and the patient who just said it was invisible will do so successfully! This seemingly bizarre phenomenon happens because the condition of blindsight leaves intact subcortical retina-to-brain pathways that can guide visual behavior, even in the absence of consciously seeing the hammer.

Rather than an effect of visual perception, this book focuses on another type of blindspot, one that contains a large set of biases and keeps them hidden. This hidden-bias blindspot shares a feature with the blind spot that you just experienced via the image of the grid and discswe can be unaware of hidden biases in the same way we are unaware of the retinal scotoma in each of our eyes. This blindspot also shares a feature with the dramatic and pathological phenomenon of blindsight. Just as patients who cant see a hammer can still act as if they do, hidden biases are capable of guiding our behavior without our being aware of their role.

What are the hidden biases of this books title? They arefor lack of a better termbitsofknowledge about social groups. These bits of knowledge are stored in our brains because we encounter them so frequently in our cultural environments. Once lodged in our minds, hidden biases can influence our behavior toward members of particular social groups, but we remain oblivious to their influence. In talking with others about hidden biases, we have discovered that most people find it unbelievable that their behavior can be guided by mental content of which they are unaware.

In this book we aim to make clear why many scientists, ourselves very much included, now recognize hidden-bias blindspots as fully believable because of the sheer weight of scientific evidence that demands this conclusion. But convincing readers of this is no simple challenge. How can we show the existence of something in our own minds of which we remain completely unaware?

Some years ago, we presented people with a test that could reveal possible hidden biasa test of their relative preference for two American cultural icons: Oprah Winfrey and Martha Stewart. A perfect and humorous example of just how unbelievable we find the idea that our behavior might be guided by information that lies in our blindspot arrived via this email: DearHarvardPeople: There is no way that I prefer Martha Stewart over Oprah Winfrey. Please fix your tests. Sincerely, Frank.

We know what Frank means. Frank does know, in the common understanding of that term, that his fondness for Oprah exceeds that for Martha. And, as his message indicates, Frank finds it simply unbelievable that his mind could additionally possess a preference about which he has no conscious knowledge. Therefore, its the test that needs to be fixed!

The self-administered test that Frank found to be so flawed is the Implicit Association Test, which we as well as many others have been studying since 1995. Just as the rectangle with the black discs allows us to see the otherwise hidden retinal blind spot, the Implicit Association Test has enabled us to reveal to ourselves the contents of hidden-bias blindspots. And where the demonstration of the retinal blind spot allows us to know that the visual blind spot exists but not much more, the Implicit Association Test (IAT) lets us look into the hidden-bias blindspot and discover what it contains.

The two of us met in Columbus, Ohio, in 1980 when Mahzarin arrived from India as a PhD student to work with Tony at Ohio State University. The decade of the 1980s brought significant changes to our branch of psychology. Psychology was on the verge of what can nowthirty years laterbe recognized as a revolution triggered by new methods that could reveal potent mental content and processes that were inaccessible to introspection. The two of us sought to learn whether these methods could be sufficiently developed to reveal and explain these unseen influences on social behavior. Looking back to that period, we can see how fortunate we were to be swept into the vortex of this revolution.