ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

From the 1989 edition:

I wish to express my deep gratitude to Tsunekazu Nishioka for his patience, good humor, advice, and support at all stages of this study and to the Reverend Kin Takada, abbot of Yakushiji temple, without whose permission this publication would have been impossible. Special thanks go also to the Reverend Joukei Fuchigami, formerly of Yakushiji, for providing information concerning the history of the temple, its sect and founder, as well as Buddhism in general. I am also grateful to Professor Hirotar ta of the University of Tokyo for his advice and criticism of my manuscript and drawings. I am especially indebted to the many carpenters, both at Yakushiji and elsewhere, who have patiently answered innumerable questions concerning terminology and procedures and have treated me so warmly.

My sincerest gratitude goes also to the many people who have made my long stay in Japan not only possible but enjoyable, particularly Professor Hisao Koyama of the University of Tokyo, who generously gave me permission to pursue this study as part of my graduate work, and without whose encouragement and assistance any extended stay in Japan would have been impossible. Thanks are due also to the many organizations upon whose assistance I have relied, particularly the Japanese Ministry of Education, the Japan Foundation, and the Ikeda Construction Company, and to those who made my first trip to Japan possible, especially Atsushi Moriyasu, who shares a deep interest in this subject and who, five years ago, surely could not have foreseen this tangible end result of a good word placed with the right people at the right time.

Finally, to Lynne E. Riggs and to everyone at Kodansha International, particularly editors Michael Brase and Shigeyoshi Suzuki and designer Shigeo Katakura, whose selflessness and unflagging energy have buoyed me up through the seas of exhaustion.

For this revised edition:

To the above I would like to add my gratitude to Director Yuji Yamazaki and the staff of Uzumasa Films for involving me, even in a small way, in their fantastic film about Nishioka, Oni ni kike [An Artisans Legacy: Tsunekazu Nishioka], and for providing the photograph on page . Thanks to my colleagues at Kanazawa Institute of Technology for accepting the amount of time I have devoted to this edition, and particularly to Miyako Takeshita, curator at my lab in Tokyo, the KIT Future Design Institute, who assisted in many aspects of research and production. Finally, to Eric Oey, June Chong, Alphone Tea, and the many others at Tuttle for their efforts in seeing this challenging book completed in a form we all can be proud of.

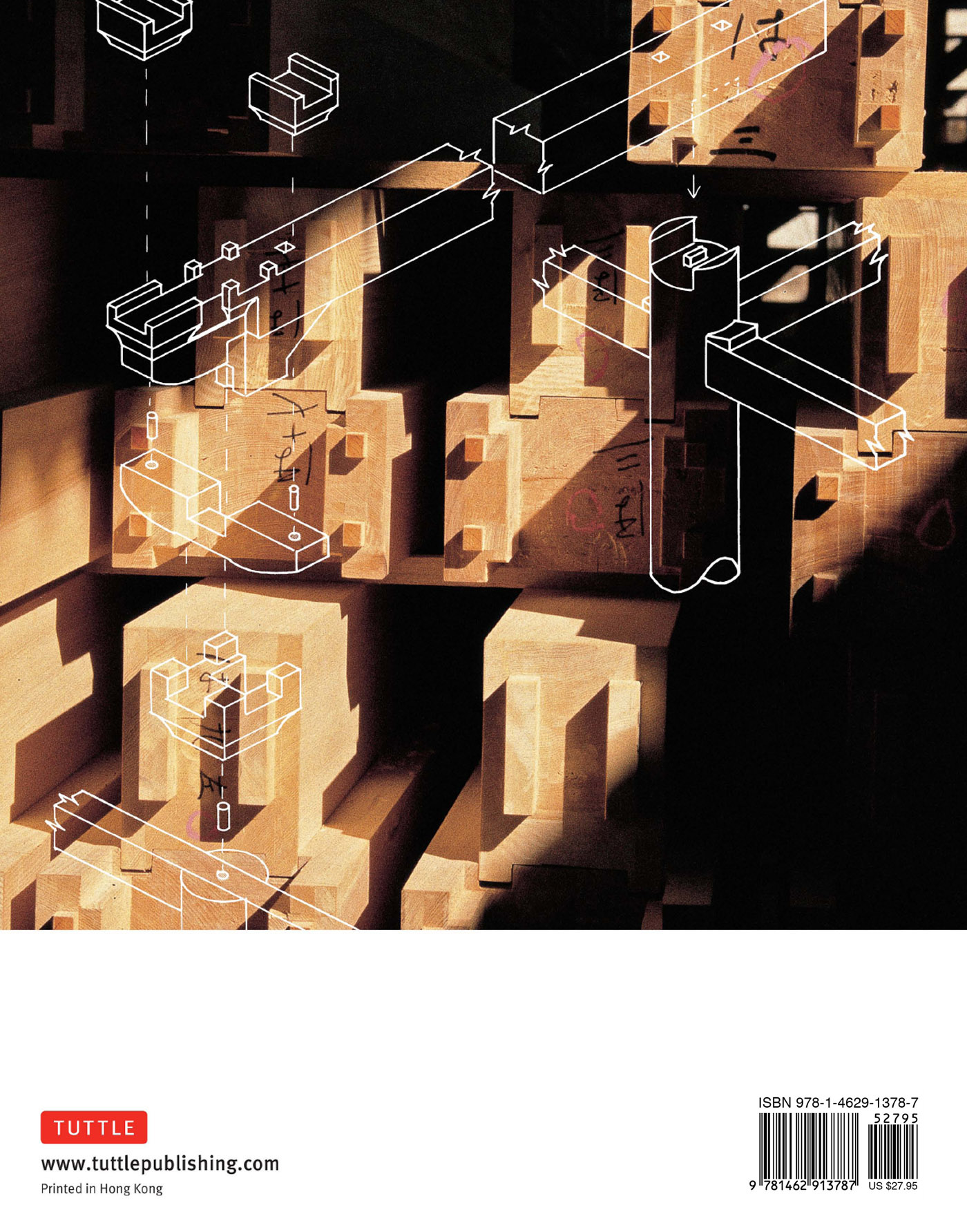

Figure 3 Completed door frames await assembly. (See also Figs..)

CHAPTER

WOODWORKING

IN JAPAN

In most discussions of traditional Japanese architecture , one of the first questions raised is why wood has been the primary building material, contrasting so sharply with the Western tradition, whose ancient monuments were almost always of stone and brick, and even with Chinese and Korean architecture, where masonry figures almost as prominently as wood. The Japanese invariably attribute their universal use of wood to the archipelagos natural endowments. Wood and bamboo have existed in abundance from primeval times, while accessible and appropriate building stone was negligible. Seismic disturbances are also frequent. Hence, the reasoning follows, practical limitations dictated an exclusively wooden architecture.

We need not, perhaps, accept this explanation at face value. After all, Japan is a mountainous country with an abundance of rock, and a glance at the stone walks of medieval gardens, or at the meticulous masonry of castle retaining walls, reveals a highly refined aesthetic sensitivity and technical sophistication. Why were these techniques not utilized in the construction of entire buildings?

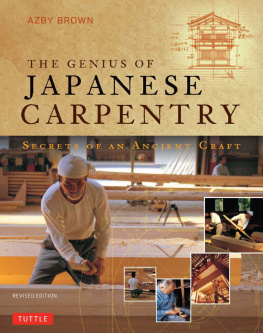

Figure 13 Master carpenter at work, from Shokunin zukushi-e , ca. 1640.

It may be that the choice of materials was influenced , much more than is generally recognized, by the manner in which mainland technology was received in Japan. Although a handful of large indigenous wooden shrine buildings preceded the introduction of Buddhist temple construction in the sixth century, the new woodworking tools and techniques represented a great leap forward in technological complexity, sophistication, versatility, and durability. Building upon woodworking methods whose rudiments were already familiar to the Japanesewe know from archaeological finds that pre-Buddhist Japanese building was chiefly in wood with the notable exception of monumental tombs that exhibit a precise fitting of huge stonesthe Japanese were able to leapfrog several centuries of technological evolution. An important point to keep in mind, however, is that this technology was quickly canonized as emblematic of the new political regime, which sponsored its development and the education of new generations of craftsmen. While there must have been ample opportunity to acquire advanced masonry techniques as well as wood, both during this early stage of Buddhist architecture and in later centuries, the bureaucratic and educational system may have resisted such a step as a costly extravagance or as a challenge to the status quo. It may be that with no clearly perceived need for a parallel stoneworking tradition, the material was relegated as a matter of course to secondary uses in podia, foundations, decorative lanterns, miniature pagodas, walkways, and, much later, castle walls. Another factor may have been the susceptibility of masonry to earthquake damage, though this would seem to be offset by its increased resistance to fire.

On the other hand, an element of consideration for the supernatural possibly influenced these choices. Part of the value system symbolized by Shint beliefs stresses love of and respect for wood as a living organism. A form of animism, Shint ascribes consciousness and personality to natural forces such as wind and rain, sun and moon, geological formations, and non-human living things. Certain mountains are held sacred, as are parts of forests and even particular trees. The presence and will of these deities, or kami , pervaded everything. Without the permission and assistance of the gods, rice will not grow, women will not conceive, and a building will not stand.

These beliefs are celebrated to this day in the form of Shint ceremonies for planting, marriage, and construction, to name a few, and although a diminishing number of people observe the old rituals, natural phenomena are still accorded a measure of respect. The almost religious reverence for wood is, fortunately for us, among the many traditions that have stood the test of time. A tree, like other natural phenomena, is believed to possess a spirit, and a carpenter, when he cuts down a tree, incurs a moral debt. One of the themes that runs throughout Japanese culture is the belief that nature exacts from man a price for coexistence. A carpenter must put a tree to uses that assure its continued existence, preferably as a thing of beauty to be treasured for centuries. There is a prayer that Nishioka would recite before laying a saw to a standing tree. It goes in part, I vow to commit no act that will extinguish the life of this tree. Only by maintaining this pledge does the carpenter repay his debt to nature.