Table of Contents

Advance Praise for The Spirit of Vatican II

Written in an inviting and accessible style, McDannells work captures the important movements in the church and American society that preceded (and prepared the way for) Vatican II, the details of the Council, and its unique effects on various parishes. The book underscores the contributions of women whose roles may not have been as public as those of male clerics but which were influential at the local level. Catholics who lived in this era will recognize the history and younger generations will learn the nuances of the history that has shaped contemporary religious experience.

Chester Gillis, Professor of Theology at Georgetown University and author of Roman Catholicism in America

Part social history, part family memoir, Colleen McDannells The Spirit of Vatican II beautifully evokes the dramatic transformation of Catholicism in the middle decades of the twentieth century. The way she entwines her stories of family and church is a breath of fresh air all its own.

Leigh E. Schmidt, Charles Warren Professor of American Religious History at Harvard University

In this engaging and compelling text McDannell uses her mothers story to trace the impact of Vatican IIs reforms on the everyday lives of American Catholics. Through the lens of family history we come to understand not only the theological, liturgical, and cultural changes the Council set in motion, but gain insight into broader issues such as immigration, family history, gender, class, region, and popular culture. McDannells accessible narrative makes important contributions to the history of religion in America.

Judith Weisenfeld, Professor of Religion at Princeton University

ALSO BY COLLEEN McDANNELL

Catholics in the Movies, editor

Picturing Faith: Photography and the Great Depression

The Religions of the United States in Practice, editor

Material Christianity: Religion and Popular Culture in America

Heaven: A History (co-authored with Bernhard Lang)

The Christian Home in Victorian America, 1840-1900

For Linda Jansen, Lillian Wondrack, Dianne Ashton, and Margaret Toscano, always there

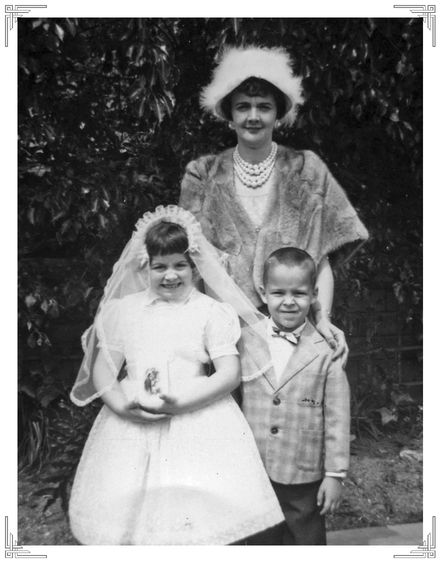

First Holy Communion, April 1962. Margaret McDannell with daughter Colleen and son Kevin.

INTRODUCTION

I am the last of a generation. In April of 1962 I received my First Holy Communion. That fall, the Catholic bishops of the world traveled to Rome to spend four years debating changes that would alter Catholicism forever.

As an eight-year-old, I was dressed like a bride but wearing white, lace-edged socks. I eagerly awaited receiving the body and blood of Christ. The Holy Names Sisters who taught me at St. Stephens school did their best to explain the meaning of the Mass. Patiently they translated its Latin texts and deciphered the ritualized gestures. Earlier in the week, I had confessed my sins to our parish priest. Those of us who would receive Communion that day had dutifully fasted for three hours. That the girl kneeling beside me fainted under the stress of the event only heightened the emotional intensity of the ceremony. It was a heady week for a second grader.

That fall would also begin four heady years for the worlds Catholic leaders. By early October 1962 over two thousand Council Fathers had traveled to Rome to attend the Second Vatican Council. The prominence of this meeting of Catholic leaders also attracted an even larger assembly of journalists, pilgrims, theological advisors, and curiosity seekers.

Dressed in their finest clerical garb, 2,540 men processed into St. Peters Basilica on the Feast of the Maternity of the Virgin Mary. These Council Fathers came from seventy-nine different countries, with the number of Americans almost equaling the number of Europeans. That total would be matched by those who came from Asia, Oceania, and Africa. The French bishops brought four tons of baggage, but the 239 Council Fathers from the United States traveled far lighter.

All had arrived in response to Pope John XXIIIs call to open a window and let in a little fresh air to the Catholic Church. The pope and many of the leaders of the worlds Catholics had decided that the Holy Spirit now required the renewal of her people. Four years had already gone into the preparation for such a discussion. Now there would be another four autumns of intense reflection on how to make the gospel of Christ relevant in a modern world.

MY FAVORITE PICTURE from the day of my First Holy Communion has me posing with my mother and brother in our California backyard. Even though I got to wear a veil and my brother sported a natty plaid jacket, it is my mother, Margaret, who steals the show. For this major rite of passage in her daughters life, she is wearing a feathered hat she made in a how-to class, fake pearls, and a mink stolejust the outfit for a southern California spring day.

My mother is also the last of a generation. In 1962 she was in full adulthood, aged thirty-six, having been born just before the Great Depression and marrying during the Second World War. Unlike hers, my generation was too young to notice the end of a particular kind of Catholicism. I grew up after the Second Vatican Council, playing guitar music at English-language Masses. I can remember my father crying in 1963 at the funeral of John F. Kennedy, but I have no memory of the day when priests turned around and faced their congregations. My mother and her generation do.

My parents are now in their eighties. Their generation flourished in spite of the profound challenges of the times, motivating some journalists to anoint them the Greatest Generation. Theirs is the last generation of Catholics to live half their lives before the Second Vatican Council and half after the Council. My parents hold their religion close to their hearts. Only a serious illness could keep them from going to Mass every Sunday. For the Catholics of the Greatest Generationthose who lived through the Depression, World War II, the sixties, and the terrorist attacks of 9/11the Second Vatican Council looms large.

Vatican Two conjures up the spirit of a defining religious moment. Catholics still talk about what things were like before Vatican II or after Vatican II. Even those who have little understanding of the specific documents of the Council can remember the excitement and turmoil of the period between 1959, when Pope John XXIII announced his plan to convene a worldwide meeting of bishops, and 1978, when Pope Paul VI died. The phrase the spirit of Vatican II refers to a constellation of changes that Catholics experienced in their homes, churches, and schools.

For Margaret, the Second Vatican Council stimulated changes that brought her more intimately in contact with the ritual and theological life of her church. Like millions of other Catholics, she was the granddaughter of immigrants. Until she left home, she had attended Mass in a highly decorated church and went to a school taught by nuns who wore equally elaborate habits. After World War II, Margarets husband took advantage of the GI Bill, and the young couple eventually moved into a newly built suburb in Toledo, Ohio. There they joined a fast-growing parish that relied heavily on the involvement of young families. Suburban Catholicism prepared many Catholics for the changes that would come from Rome in the sixties. However, when Margaret moved to Los Angeles, her California parish had a pastor who showed no interest in altering how Catholicism was practiced. Only after Margaret and her husband moved to Denver, Colorado, did they experience the full implications of the Second Vatican Council. Margaret enthusiastically embraced the Spirit of Vatican II at her new exurban parish. She joined with other men and women to distribute Communion at Mass, sing folk songs, and call their pastor by his first name. Now retired and living in central Florida, the couple no longer go to a Mass with guitars, but Margaret still enjoys her womens Bible-study group and supports the churchs sister parish in Uganda.