Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Acknowledgements

Researching and writing a book like this makes one incur all manner of debts, personal and professional. Over the past five or so years, discussions with a large number of colleagues, friends, and/or students have helped to refine my ideas. These includein no particular orderDr Jacob Phillips, Victoria Seed, Fernanda Mee, Susan Longhurst, Hannah Vaughan-Spruce, Tim Kinnear, Julie Mersey, Marc Barnes, Fr David Poecking, Revd Dr Greg Murphy OP, Dr Maria Power, Mgr Andrew Burnham, Dr Damian Thompson, Greg Daly, Dr Brendan Ryan, Dan Hitchens, Luke Coppen, Gavan Ryan, Andrew Tucker, Caroline Farrow, Fr Robin Farrow, Jordan Summers Young, Paul Summers Young, Prof. Philip Booth, Prof. John Charmley, Prof. Francis Campbell, Revd Dr Ashley Beck, Prof. Peter Tyler, Dr Jon Lanman, Dr Hugh Turpin, Dr April Manalang, Dr Ben Clements, Dr Lois Lee, Dr Miguel Farias, Fr Ian OShea, Mgr John Walsh, Mgr Richard Madders, Br Shaun Bailham OP, Dr Brett Salkeld, Dr Catherine Pakaluk, William Johnstone, and Dr Joseph Shaw. I am especially grateful to Dr David McLoughlin for the wonderful vignette of post-war Catholic Birmingham quoted in .

A number of kind and constructively critical souls deigned to read and comment on various draft chapters: Revd Dr Stephen Morgan, Fr David Palmer, Dr Shaun Blanchard, Luke Arredondo, Fr Hugh Somerville-Knapman OSB, Dr Christopher Altieri, and Dcn Tom Gornick. These, along with OUPs anonymous peer reviewers, have made this a vastly better book than it could otherwise have been.

Marc Barnes did some sterling Research Assistant-ing towards gathering the data included in the Appendix. Maura McKeegan Barnes did a brilliant job in whipping the final manuscriptalong with my various Britishisms, slang terms, and (she says) egregious slurs against Peter, Paul, and Maryinto submittable shape.

At Oxford University Press, Tom Perridge and Karen Raith have been the excellent and indulgent editors I have come to expect.

Several of the main ideas in Mass Exodus, and the odd bit of its phrasing, have been previously road-tested on the readers of various periodicals, including Catechetical Leader, Pastoral Review, America, the Tablet, andabove allthe Catholic Herald.

Most of all, though, I wish to express my deepest love and gratitude to my wife Joanna, daughters Grace and Alice, and baby son Francis: the best and most lovable family a man could ask for. Thank you for letting daddy write another of his boring, boring, boring books.

Contents

On 11 October 1962, Pope John XXIII formally opened the Second Vatican Council. Its avowed purpose was, he told the thousands assembled in St Peters Basilica, to really succeed in bringing men, families and nations to the appreciation of supernatural values. While this would require some timely changes to keep up to date with the changing conditions of this modern world, and of modern living, John declared that the Church must never for an instant lose sight of that sacred patrimony of truth inherited from the Fathers (John XXIII ).

Vatican II ran until December 1965, outliving its convoker by two and a half years. With a serious claim to being the biggest meeting in the history of the world (OMalley

The prominence Vatican II accorded to the laity is striking, especially in light of prior councils reticence on the subject. It declares, for instance, that the laity, dedicated to Christ and anointed by the Holy Spirit, are marvellously called and wonderfully prepared so that ever more abundant fruits of the Spirit may be produced in them (Lumen Gentium 34). As befits those called to consecrate the world itself to God (Lumen Gentium 34), and possessing their own apostolate of evangelization and sanctification (Apostolicam Actuositatem 6), the laity are thus not only bound to penetrate the world with a Christian spirit, but are also called to be witnesses to Christ in all things in the midst of human society (Gaudium et Spes 43). This stirring vision of the laity has been enthusiastically received among commentators. To cite only recent examples, it is described as a central and crucial element of the legacy of the council (Lakeland : 1213).

* * *

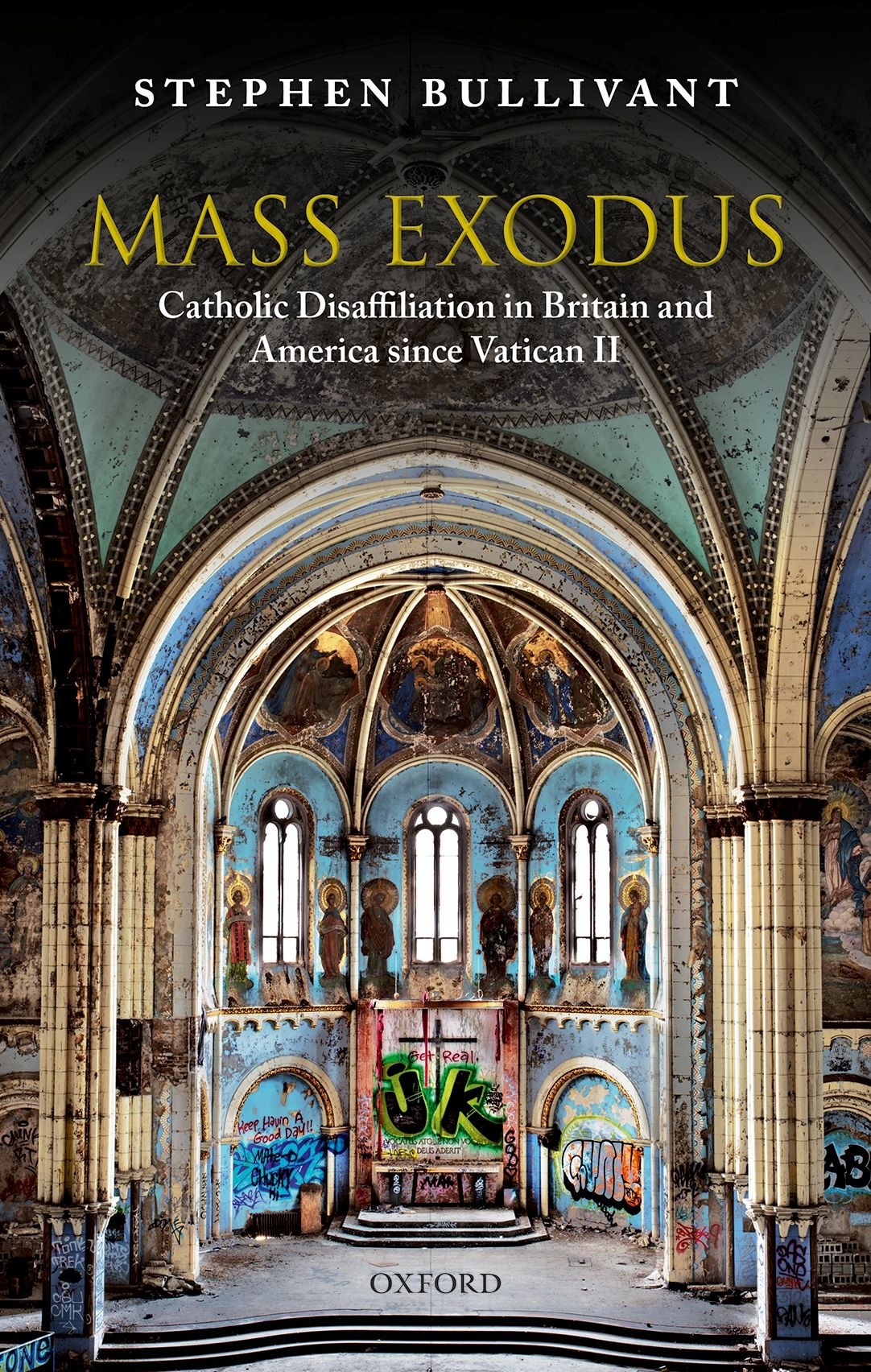

It is now over fifty years since the close of Vatican II. According to recently published British data, nearly half of all born-and-raised Catholics no longer consider themselves to be Catholic; the vast majority of thesealmost two out of every five British cradle Catholicsclaim to have no religion. These leavers from Catholicism outnumber converts to Catholicism by a ratio of ten to one. Furthermore, among those who do still identify as Catholic to pollsters, somewhat fewer than one in three attend church on a weekly basisroughly the same proportion as attend never or practically never (Bullivant ).

Towards the end of his detailed and nuanced study of the collapse of Bostons Catholic culture, the journalist Philip Lawler observes:

Today, former Catholics constitute the largest religious bloc in the Boston area. Some of these ex-Catholics have joined other religious bodies. Others take no interest in religious affairs. Still others think of themselves as Catholic, but they neither practice their faith nor honour its teachings. In the opening years of the twenty-first century, practising Catholics are once again a small minority in Boston [ ].(2008: 247)

Boston, once Americas archetypal Catholic town, may be a special case. But it is not that special. Leading American sociologist Michael Hout notes, More than ever, people raised Catholic are leaving; most drop out of organized religion altogether (: 1). In the view of the Fordham historian Patrick Hornbeck: deconversionthe process of moving from identification and active engagement with Roman Catholicism to disaffiliation and disengagementis one of the most theologically significant phenomena in contemporary American Roman Catholic life (2011: 1).

![Pope John XXIII - The Roman Missal [1962]](/uploads/posts/book/272720/thumbs/pope-john-xxiii-the-roman-missal-1962.jpg)