Contents

Guide

Page List

Table of Contents

The Collected Works of Spinoza

Eerfte Deel

Der

Z E D E K U N S T .

V A N G O D .

B E P A L I N G E N .

I.  Y wezentlijk, bevat kan worden.

Y wezentlijk, bevat kan worden.

II. Datding, t welk door een ander van de zelfde natuur denking door een andere bepaalt. Maar t lighaam word door geen denking, noch de denking door enig lighaam bepaalt.

III. By gevormt moet worden, behoeft.

IV. By bevat.

V. By zelfftandigheit, ofdit, t welk in iets anders is, daar door het ook bevat word.

VI. By God verfta ik een wezentheit uitdrukt.

Canfa fai.

Effentia.

Exiftentia.

Involvere.

Exiftens.

Terminare.

Genus.

Finita.

Corpus.

Cogitatie.

Subftantia.

Conceptus.

Formare.

Attributum.

Intellectus.

Subftantia.

Effentia.

Conflituens.

Concipere.

Modus.

Affectiones.

Subftantia.

Ens.

Abfolut.

Infinitum.

Subftantia.

Attributa infinite.

Conflare.

Effentia.

f VER

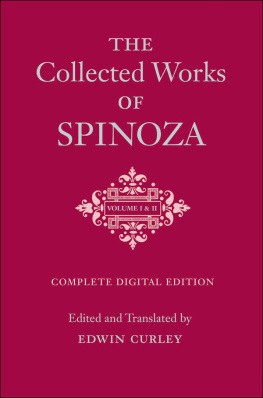

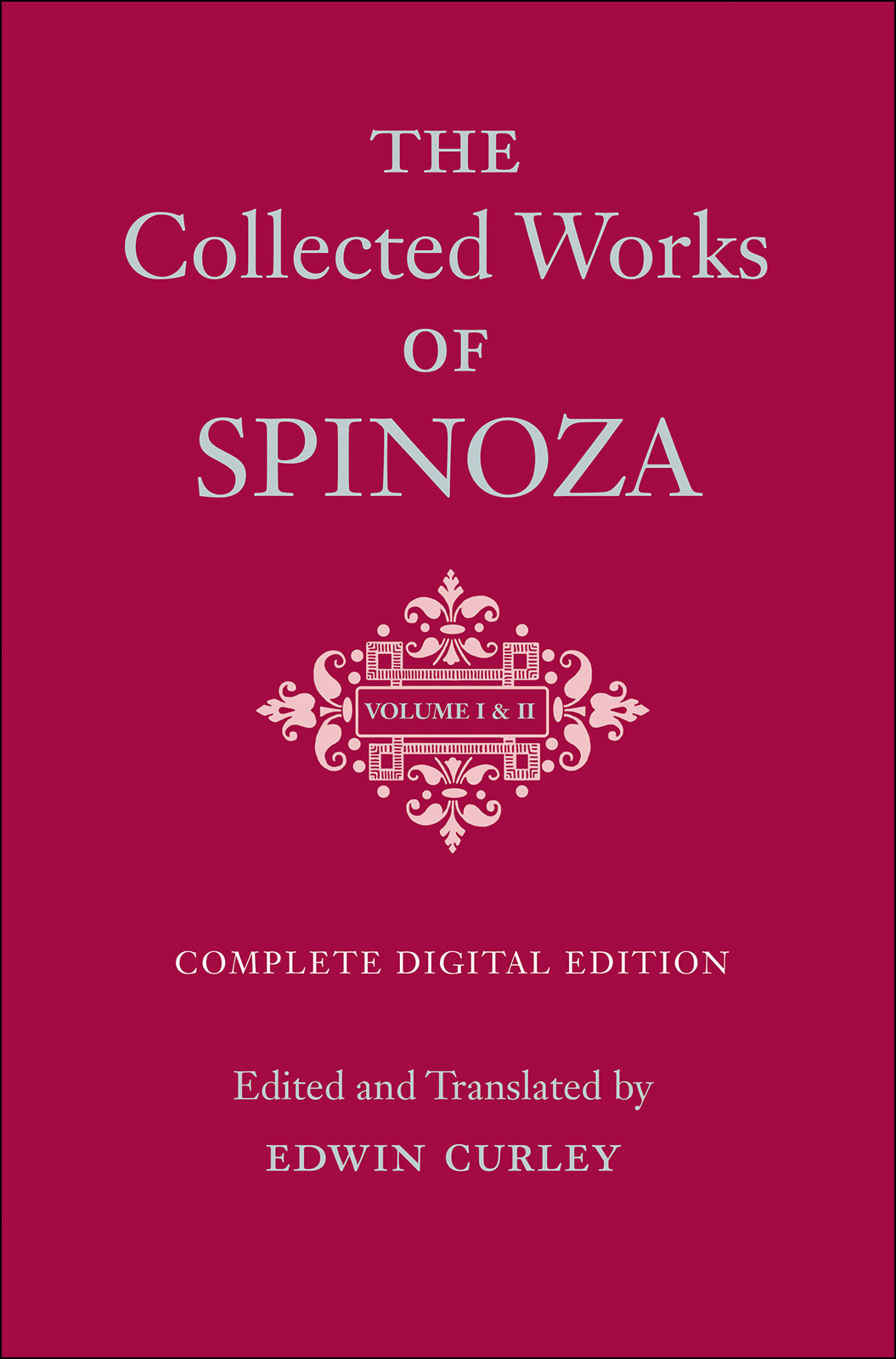

THE

Collected Works

OF

SPINOZA

Edited and Translated by Edwin Curley

Copyright 1985 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University

Press, Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Spinoza, Benedictus de, 1632-1677.

The collected works of Spinoza.

Includes bibliographies and index.

1. PhilosophyCollected works.

I. Curley, E. M. (Edwin M.), 1937- . II. Title.

B3958 1984 199.492 84-11716

ISBN 0-691-07222-1 (v. 1 : alk. paper)

This book has been composed in Linotron Janson type

Princeton University books are printed on acid-free paper

and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the

Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the

Council on Library Resources

Printed in the United States of America by

Princeton Academic Press

Second printing, with corrections, 1988

10

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-07222-7 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 0-691-07222-1 (cloth)

A LL OUR knowledge of Scripture must be sought from Scripture itself alone. The universal rule for interpreting Scripture is that we must attribute nothing to Scripture as its teaching which we have not seen most clearly on the basis of an historical inquiry. The kind of historical inquiry I mean must I. take account of the nature and properties of the language in which the books of Scripture were written II. collect the doctrines of each book and so organize them that we can readily find all those that bear on the same topic; and next, note all those which are ambiguous or obscure or which seem contradictory finally, III. tell the circumstances and fate of all the prophetic books of which we have any record: the life, dispositions and intentions of the author of each book, who he was, when and on what occasion he wrote, to whom and in what language; how the book was first received, into whose hands it fell, how many different readings there are of the text, who first accepted it as sacred, and finally how all the books now agreed to be sacred were united into one.

Theological-Political Treatise, vii (

Contents

General Preface

T HIS IS the first installment of what is intended to be a two-volume edition of the complete works of Spinoza, with new translations. The project is one I have been working on, intermittently, for some fourteen years now. My aim in undertaking it has not been primarily to provide English readers with translations better than the existing ones, though I would hope, of course, to have done that. My goal, however, has been more to make available a truly satisfactory edition, in translation, of Spinozas work. Let me enumerate the features I regard as required in a satisfactory edition.

1. That it should provide good translations is only the most obvious, though no doubt the most important, requirement. No one should underestimate the difficulty of meeting it. By a good translation I understand one which is accurate wherever it is a question of simple accuracy, shows good judgment where the situation calls for something more than accuracy, maintains as much consistency as possible in the treatment of technical terms, leaves interpretation to the commentators, so far as this is possible, and, finally, is as clear and readable as fidelity to the text will allow. Anyone may be excused for thinking it enough just to provide good translations. Often we have had to settle for rather less.

2. Still, we have a right to expect more of a truly satisfactory edition. One further requirement is that its translations should be based on a good critical edition of the original texts. Of the works presented in this volume, only two, Descartes Principles of Philosophy and the Metaphysical Thoughts, were published during Spinozas lifetime. The Ethics, the Treatise on the Intellect, and most of the letters were first published in the Opera posthuma (OP) shortly after Spinozas death in 1677. The Short Treatise was discovered only in the nineteenth century, in what is generally presumed to be a Dutch translation of a lost Latin original. Inevitably these works raise many textual problems.

The first editor to produce a genuinely critical edition of the original texts was Gebhardt, whose four-volume edition of Spinozas Opera appeared in 1925.

One of the principal initial reasons for undertaking this project was to provide translations based on the Gebhardt edition. When I began, Spinozas masterwork, the Ethics, had never been translated into English from Gebhardts text, though other, lesser works had been. Existing translations were based on inferior nineteenth-century editions. And though Wolfs excellent translation of the Short Treatise had been based on a careful study of the original manuscripts, there was no doubt that his work had been superseded by Gebhardts.

During the time I have been working on this project, much has happened. We do now have an English translation of the Ethics based on the Gebhardt text. But while Gebhardts remains the best available complete edition of the texts, it has, in its turn, been superseded, to some extent at least, by a number of recent scholarly works. Of the developments relevant to this volume, the most notable are that: 1) in 1977 the Wereldbibliotheek published, as the first installment in a new Dutch edition of the complete works, an edition of the correspondence, undertaken by Professors Akkerman, Hubbeling, and Westerbrink (AHW); although this edition presents all the letters in Dutch, the editors have taken great pains to get an exact text, and their work must be treated as the equivalent of a new critical edition; 2) in 1982, the third installment of the Wereldbibliotheek series contained a new critical edition, by Professor Mignini (Mignini 1), of that most troublesome of all Spinozistic texts, the

Y wezentlijk, bevat kan worden.

Y wezentlijk, bevat kan worden.