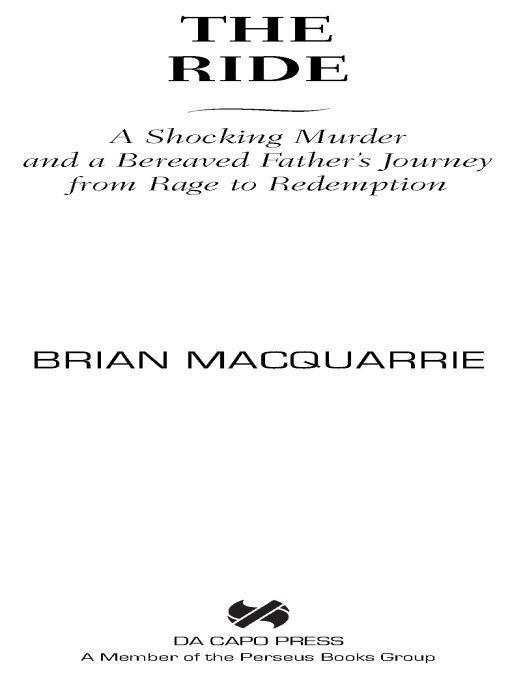

Table of Contents

To the Curley family and to all missing children.

Prologue

HUNDREDS OF PEOPLE huddled in the autumn air, waiting for the words of a grieving, shattered family. Parents held their children, mouthed a prayer, or simply hugged their numbed neighbors in a communal search for solace. Bob Curley, a Fire Department mechanic, approached a bank of microphones and looked into the stunned and disbelieving faces of East Cambridge, a community shaken to its core by his sons horrific death.

The unthinkable had happened here.

Bob had never spoken to a large group before. But today, with a compelling natural eloquence, he issued a chilling warning, coupled with a loud call for action.

My Jeffreys not going to feel no more pain, Bob said, his voice clear, angry, and commanding. But my Jeffrey died with the heart of a lion. I know that. And thats why God put this on us. Because were gonna take it, and were gonna go forward, and all you people remember this!

Bobs neighbors nodded, many of their faces lined with tears. Children who could not understand this agitated man, but were frightened by his rage, tugged their mothers a little closer.

Remember Jeffrey! Bob said. Remember the pain you feel now! Remember how scared you are now! Well all stand tall as a community, and well work to change the laws. Well work to keep maggots like this away from our children.

The time had come to bring the death penalty back to Massachusetts, Bob ranted, in the opening salvo of a bitter, personal crusade that would radically transform his life.

God love you all, Bob concluded, his voice cracking with emotion. Thank you so much. Its been so hard.

Inman Square

BOB CURLEY rolled out of bed, tossed a glance toward the Boston skyline three miles away, and dressed for another days work at the Cambridge Fire Department. There would be no dawdling for Bob, a broad-shouldered, good-looking man with thick brown hair, glinting blue eyes, and the no-nonsense look of this edgy neighborhood, where grit was as embedded in its men as in its cracked and crumbling sidewalks.

Bob hustled out the door at 6:45 A.M., only a quarter hour after waking up and less than two miles from the firehouse, where he and another mechanic repaired and prepped the ladder, hose, and pumper trucks that raced through one of the most densely populated cities in the country.

The morning was October 1, 1997, a warm, Indian summer Wednesday when New England was awash in a season-bridging spectacle of color.

Bob, at forty-two, commuted to work on a battered bicycle, coasting down a steep hill from his new home in East Somerville, a curmudgeonly cousin to the Inman Square streets where he was raised and now worked. At the bottom of the descent, Bob blocked out the jarring sound of heavy trucks bouncing in and out of gaping potholes and banked hard into a right-hand turn.

There, Bob entered what he called the ghetto, an unsightly stretch of ungroomed growth pocked by jagged, uneven pavement; honking, impatient traffic; and a hilly warren of narrow, one-way streets. Focusing on the pedals, not the panorama, Bob passed a grimy repair shop, a Brazilian church, the tired facade of Buddys Diner, and half-organized graveyards for used auto parts, where old mufflers and piles of rusting radiators lay stacked against the neglected sides of sagging buildings.

Just after a confusing slalom of twists and turns through Union Square, Bob rose from his bicycle seat, legs pumping like pistons, to scale a short, tough incline beside the commuter-rail tracks. Atop the crest, breathing hard, Bob cruised through a cheek-by-jowl neighborhood of modest, two-story, wooden homes, a well-tended place of front-yard Madonnas and corner stores that had yet to fall victim to the gentrification creeping through Greater Bostons blue-collar core.

Finally, after catching his breath, Bob veered left on Springfield Street several blocks away, where he could see the Renaissance design, graceful bay doors, and soaring bell tower of the century-old Inman Square firehouse. And near the square, where scraps of early-morning litter blew across a junction of six chaotic city streets, a small sidewalk sign marked the indistinguishable boundary between Cambridge and Somerville.

Here, in Inman Square, Bob had matured from boy to man, fathered three children, and found a steady job among the people, sights, and sounds that had anchored him in good times and bad. The neighborhood was his turf and always had been, a cocky, changing crossroads of Irish pubs, upscale coffee shops, gay bookstores, and Portuguese social clubs that had managed to retain a spit-on-the-sidewalk chippiness from its immigrant past.

Whether it was the sports talk that attracted Bob to the bare-bones Abbey Lounge or the politically incorrect banter from third-generation firefighters, Bob loved this place as much as ever, even as the hard-drinking mens bars and bottom-dollar barber shops that had long ruled its unpretentious social life had all but disappeared.

The place remained a comfort zone that kept Bob grounded, even if trauma had distorted his childhood there. His father, John, a transplant from St. Joseph, Missouri, had been a gambler and serial womanizer who left the family when Bob was twelve. Money was scarce, clothing could be shoddy, and domestic tranquility was seen only on television. To escape, the boy sometimes retreated to an attic room he called the Tomb, where he could lock out, if not forget, the dysfunction that roiled his family.

For family outings, Bobs father would cart some or all of his six children across the city to Suffolk Downs, a scruffy, third-rate, thoroughbred racetrack in East Boston, where the desperate could bet on a miracle from an overused nag. And while John Curley tried his luck, something he did nearly every day of the racing season, the children amused themselves in the racetrack parking lot. If John won, the clouds lifted, and the family would stop for ice cream on the ride home or venture to Revere Beach for a roast beef sandwich at Kellys. But if he lost, which was often, there were neither treats nor conversation. Bob, a quiet kid not quite seven years old, thought this was how most people spent their summers.

On October 1, 1997, those days had long been consigned to the past. And at 7:00 A.M., Bob wheeled his bicycle into the landmark brick firehouse, home to Engine 5, where a hose-carrying truck and bright red pumper screamed through Inman Square more than two thousand times a year. The men of Engine 5 called the company The Nickel. And like firefighters everywhere, their camaraderie was a palpable, living thing that bound them with an intimate communal history, where shared worries and hopes, success and failures, were often felt more intensely than within their own families. If you get in a pickle, call The Nickel, boasted the companys informal motto. And Curley, who had worked at Inman Square for three years, was an integral, upbeat, dependable part of that fraternity. Nearly everyone liked Bob, whose quick humor, passion for Boston sports, and stoic work ethic fit neatly into the fabric of Engine 5.

A man of routine, Bob walked to the rear of the firehouse to a cramped repair area he called his office, a place where a box of corn flakes and a container of milk always lay stashed in a small refrigerator. After breakfast, Bob strolled past the dispatchers desk and climbed the stairs to the second-floor kitchen for coffee, gossip, and head-shaking regrets that the Boston Red Sox, a fourth-place team in the death throes of a dreadful season, would not be World Series champions for the seventy-ninth consecutive year.