Published in 2013 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2013 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2013 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Adam Augustyn: Assistant Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Robert Curley: Senior Editor, Science and Technology

Rosen Educational Services

Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Brian Garvey: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Richard Barrington

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Explorers of the Renaissance/edited by Robert Curley.

p. cm.(The Renaissance)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-881-1 (eBook)

1. ExplorersJuvenile literature. 2. Discoveries in geographyJuvenile literature. I. Curley, Robert, 1955

G175.E965 2013

910.9224dc23

2012015599

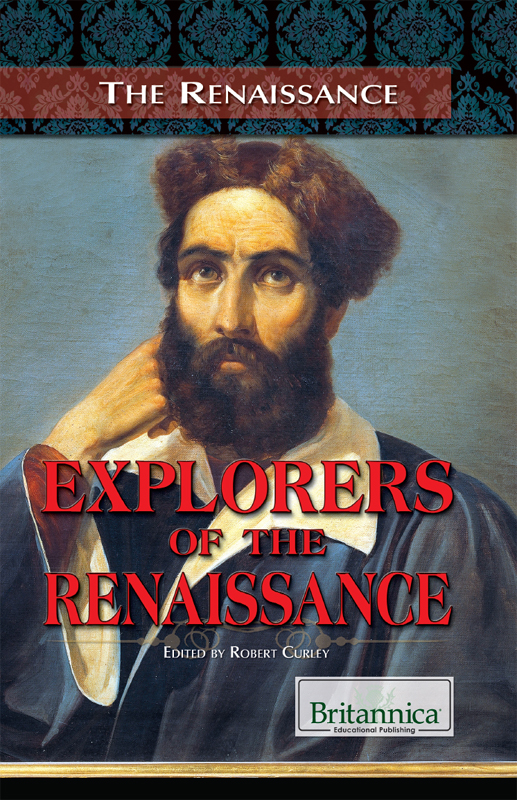

On the cover, p. iii: Portrait of Marco Polo by Annibale Strata. DEA/D.Dagli Orti/Getty Images

Cover (background pattern), pp. i, iii, 1, 23, 50, 70, 92, 115, 141, 142, 144, 147 iStockphoto.com/fotozambra; p. x (sun) Hemera/Thinkstock; remaining interior graphic elements iStockphoto.com/Petr Babkin

T he Renaissance is known as a time of tremendous artistic and intellectual achievement, but the accomplishments of the era were not solely triumphs of the mind. Great physical courage and stamina were needed by the explorers of the era, who stepped or sailed into the unknown to expand the boundaries of world knowledge. In detailing the achievements of explorers during what is known as the Age of Discovery, this book tells the story of that era; it is to be as much a tale of action and adventure as it is of the mind and spirit.

Though this story played out some 500 or more years ago, there are elements to it that are easily recognizable today. Religious and political tensions, technology, and commerce all fueled the progression of exploration throughout the Age of Discovery. Overland routes from Europe to Asia gave way to the development of seaborne eastward routes, which then led to westward exploration by sea in an attempt to reach Asia by circling around the far side of the world.

Religious conflict was an important spark to this progression, as the emergence of the Muslim Ottoman empire made overland routes to China and the court of Kublai Khan increasingly perilous for Christian European travelers and traders. Indeed, converting the great Khan and his Mongol empire to Christianity was a goal of some early Renaissance expeditions to east Asia. However, politics also played a hand, first when the breakup of the Mongol empire further increased the risks of overland travel to the region, and later when European nations jostled for the upper hand in exploring, trading with, and ultimately conquering new lands.

As for technology, its role was largely manifested in the development of navigational and shipbuilding techniques throughout this period. Until the Renaissance, navigation had progressed little since the time of Ptolemy in the second century CE. During the Renaissance, more ambitious exploration by sea took advantage of, and ultimately accelerated because of, navigational advancements. While basic navigation may not be thought of as high technology by modern standards, for its time it may be considered comparable to the Internet and air travel, regarding how it facilitated commerce and movement, and even to space exploration in that an element of the unknown was involved.

Commerce also was a constant driver behind the Age of Discovery. This was the case from the first wave of Renaissance exploration, which included the journeys of Marco Polo and a multitude of other great overland explorers.

Marco Polo was not the first European to venture eastward to Asia. The Mongol invasion of Eastern Europe had piqued, or perhaps even forced, European curiosity about the Far East; prior to Marco Polos journeys, Pope Innocent IV and King Louis IX of France each had sent emissaries to the Mongol Empire. Marco Polos own father, Niccol, and uncle, Maffeo, were both successful and far-reaching traders. It was in their company that Marco made his great trek into Asia.

This journey resulted in Marco Polo living in China for 16 or 17 years. He was originally sent with letters to Kublai Khan from the new Pope, Gregory X, and subsequently seems to have established himself in Kublai Khans court. But what gave Marco Polo lasting significance was that his travels were chronicled in a vivid and popular manuscript known as Il milione. The production of this book was something of a fluke, as it resulted from Marco Polos meeting a writer while imprisoned by a rival community of traders. The accuracy of some of the works content is questionable. Yet in spite of this somewhat shaky background, Il milione was a highly important work that helped inspire subsequent waves of European adventurers.

The Sea Discoveries Monument in Lisbon, Portugal. Henry the Navigator (far right) leads a cavalcade of Portuguese explorers who set sail during the Age of Discovery. Jose Elias/Lusoimages/Flickr/Getty Images

Not all the great explorers of the age were European. Ibn Baah, a Moroccan, was said to have traveled 120,000 km (75,000 miles) throughout Asia and Africa. He helped set the tone for the spirit of discovery with his personal policy, which was never to travel any road a second time.

What Ibn Baah and Marco Polo have in common is that both left behind widely read accounts of their travels. Chronicles of this kind proved to be important on many levels. They helped widen knowledge about geography at the time and have provided subsequent generations of historians with important firsthand accounts of the cultures and events these adventurers witnessed in their travels. Perhaps most important, these tales of far-off lands helped fuel the appetite for exploration, which was about to make a major move forward by turning toward the sea.

The transition to seaborne exploration was made possible by advances in shipbuilding technology. Around the 15th century, Spanish and Portuguese shipbuilders developed a 23-m (75-foot)-tall sail craft called the caravel, which was instrumental in extending the reach of seagoing European explorers. The galley ships that preceded caravels still relied on teams of rowers. The space taken up by these men left limited room for cargo and supplies, which made galley ships unsuitable for long journeys. In addition, caravels were capable of comparatively impressive speeds and also were able to sale strongly into the wind.