Published in 2014 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2014 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2014 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group

Adam Augustyn: Assistant Manager, Core Reference Group

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Kenneth Pletcher, Senior Editor, Geography

Rosen Educational Services

Shalini Saxena: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Brian Garvey: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Richard Barrington

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Explorers of the Late Renaissance and the Enlightenment: from Sir Francis Drake to Mungo Park/edited by: Ken Pletcher.First Edition.

pages cm.(The Britannica Guide to Explorers and Adventurers)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-62275-029-0 (eBook)

1. ExplorersBiography. 2. Discoveries in geography. I. Pletcher, Kenneth, editor.

G200.E885 2013

910.92'2dc23

2012043124

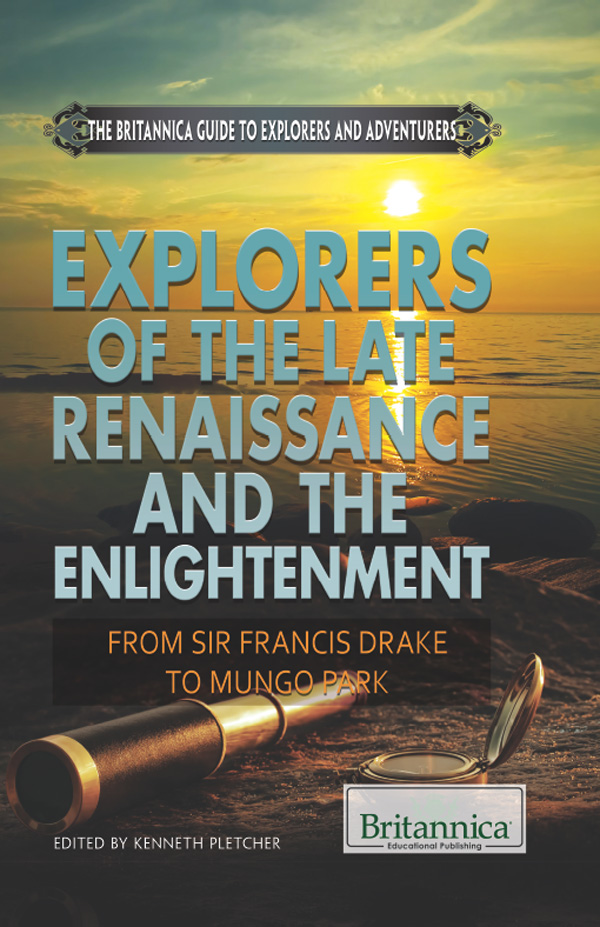

On the cover: An antique brass telescope and compass lying on a sea coast. Sergej Razvodovskij/Shutterstock.com

Cover, p. iii (ornamental graphic) iStockphoto.com/Angelgild; interior pages (scroll) iStockphoto.com/U.P. Images, (background texture) iStockphoto.com/Peter Zelei

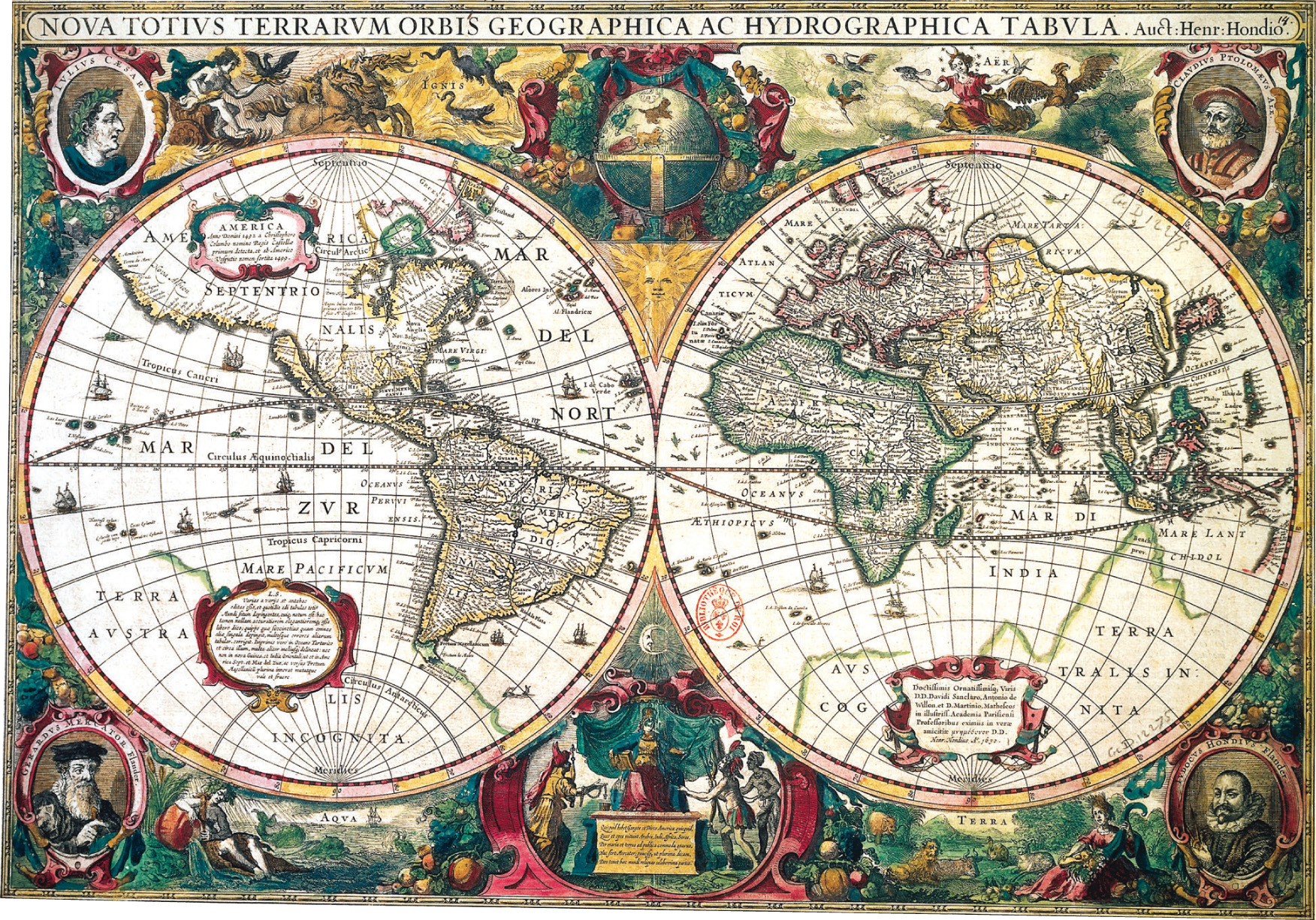

I n the early Renaissance, explorers sailed off the maps of the day, beyond the limits of what was known to their civilization. As a result, by the mid-1500s, most of the worlds large, habitable land masses had been discovered, and Earth itself had been circumnavigated. Thus, educated people of the time had a reasonable outline of what their planet looked like. It was up to explorers of the late Renaissance and Enlightenment to fill in most of that outline.

Explorers of the late Renaissance and the subsequent period known as the Enlightenment did not so much discover new wholly unknown lands as explore the potential of places that were still a mystery to people of the time. By searching and surveying, they learned which areas had fertile lands, navigable rivers, and valuable natural resources. As a result of these efforts, explorers of the late Renaissance and the Enlightenment helped determine where hundreds of millions of people live today.

History owes a great debt to these intrepid souls, but their motives and methods were not always noble. They were often in search of wealth for themselves and conquest for the countries they served, and as a result some had little regard for the rights and lives of the native peoples they found in the lands they explored. This makes it a complicated period of history. For example, Pedro Menndez de Avils has a lasting place in history as founder of the oldest city in the United States: St. Augustine in what is now Florida. Nonetheless, he was also a brutal military commander who in at least one instance slaughtered his vanquished enemies. This was just one example of the steep price some would pay for European supremacy in North America.

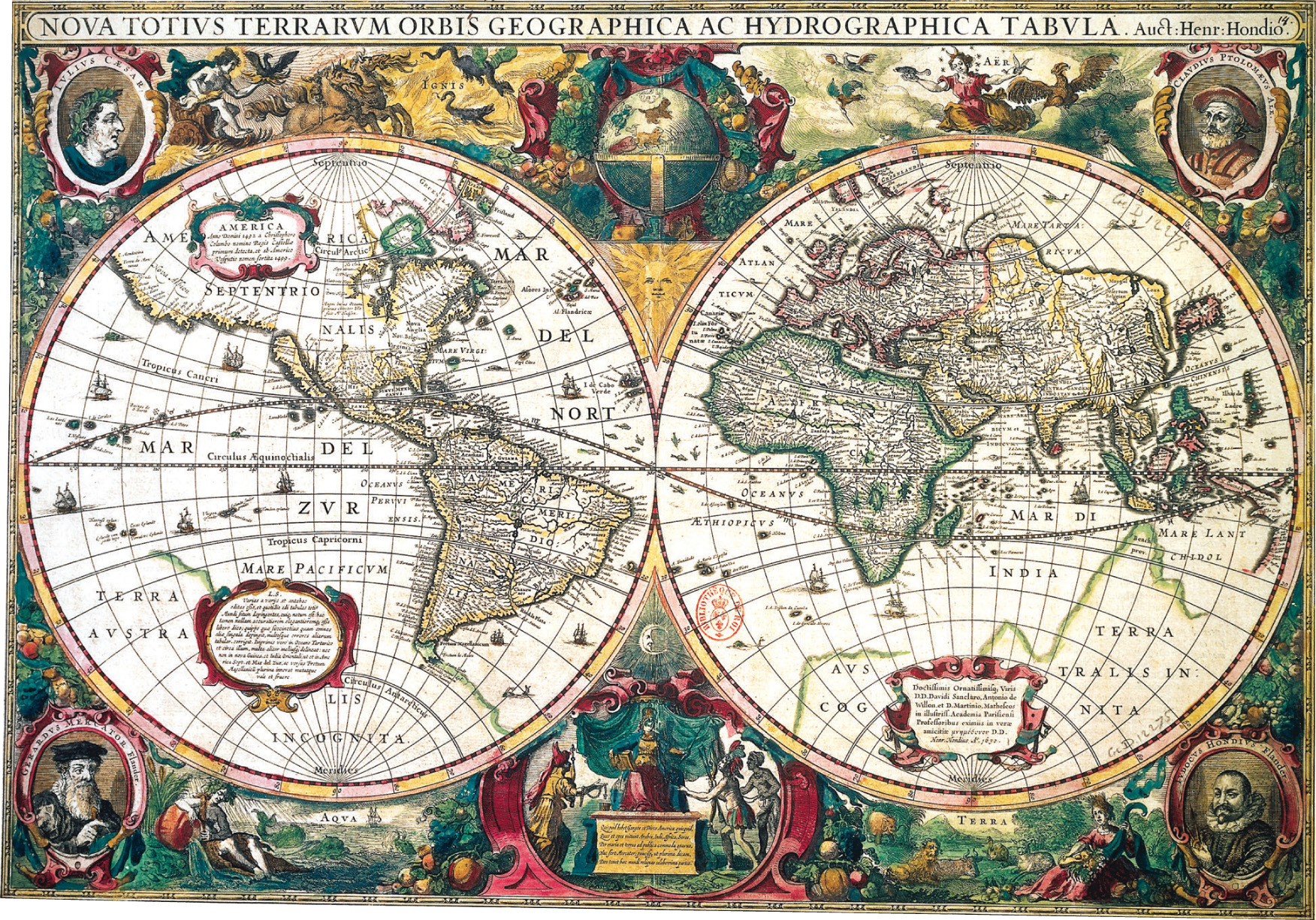

Map of the world entitled Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Geographica ac Hydrographica Tabula, created by Dutch cartographer Henricus Hondius, 1630. DEA Picture Library/De Agostini/Getty Images

While some explorers of the late Renaissance were establishing the footholds for what were to become Europes colonial empires, others were intent on furthering trade around the world. These ventures also have a mixed historywhile many resulted in trade agreements that helped foster new relationships among nations, they also introduced the slave trade between Africa and the Americas and gave rise to a predatory class of sea explorers known as privateers. Privateers were essentially pirates sanctioned by a country and given license to prey on the ships of enemy countries in exchange for whatever wealth they found on board.

Whether a privateer was considered a hero or a rogue depended on each countrys point of view, and some privateers achieved legendary status. Such was the case with Sir Francis Drake of England, a privateer in the latter part of the 16th century, when Queen Elizabeth I ruled England. Like many of his contemporaries, Drake made his fortune by plundering the ships and possessions of other countries, though he did it in a more spectacular fashion than most. After becoming the first Englishman to sail between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans via the Strait of Magellan at the southern tip of South America, Drake would ultimately become the second sea captain to circumnavigate the globe. First, though, he took advantage of the element of surprise to enrich himself and to strike a blow to Spain, then Englands greatest adversary.

Prior to Drakes voyage, only Spanish ships had made it to the western side of South America. Although his expedition was down to one small ship at that point, Drake succeeded in raiding unsuspecting Spanish settlements and ships sailing along the Pacific coast of South America. Drakes exploits were among several factors that elevated tensions between England and Spain, and by the late 1580s the Spanish were preparing to invade England with a massive fleetthe Spanish Armada. (Drakes name would become forever linked with Englands defeat of the Armada, though his role in the victory seems to have been limited to leading a raid that damaged the fleet in advance of the attempted invasion.) Drakes career is a prominent example of how some explorers of the era walked a thin line between ruthless pirate and national hero.

Drakes feat of sailing west and south to reach the Pacific Ocean was still unusual for its time because the journey was long and dangerous. Some explorers in the late 16th century began to seek an alternate route, known as the Northwest Passage. The idea was to sail north of the North American landmass and find a faster route to the Pacific via the Arctic Ocean. This objective was of particular interest to explorers from northern European nations such as the Netherlands and England, as these nations would have the most direct access to a northern sea route.

Ultimately, the Northwest Passage proved to be elusive, despite the efforts of explorers such as Willem Barents and Henry Hudson. Still, efforts to find that route cannot be dismissed as complete failures because they led to advances in navigation and to more precise charting of the northern seaways. These advances in the science of exploration were consistent with the Enlightenment, a period of intellectual discovery that followed the Renaissance in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries.