Published in 2013 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2013 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2013 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Adam Augustyn: Assistant Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Robert Curley, Senior Editor, Science and Technology

Rosen Educational Services

Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Brian Garvey: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Richard Barrington

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Scientists and inventors of the Renaissance/edited by Robert Curley.First edition.

pages cm.(The Renaissance)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-884-2 (eBook)

1. Science, Renaissance. 2. ScientistsEuropeHistory17th century. 3. InventorsEuropeHistory17th century. 4. ScienceEuropeHistory17th century. I. Curley, Robert, 1955 editor.

Q125.2.R456 2013

500.92'24dc23

2012020369

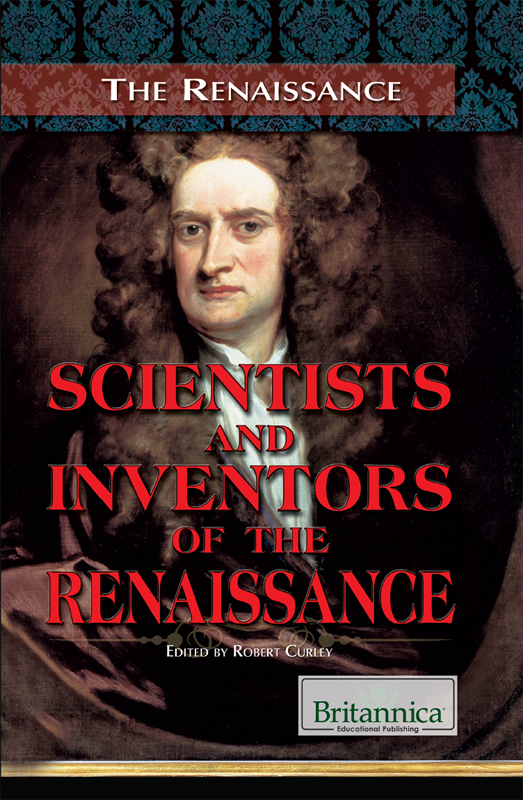

On the cover, p. iii : Sir Isaac Newton. Science & Society Picture Library/Getty Images

Cover (background pattern), pp. i, iii, 1, 35, 73, 98, 136, 155, 156, 158, 161 iStockphoto.com/fotozambra; p. x (sun) Hemera/Thinkstock; remaining interior graphic elements iStockphoto.com/Petr Babkin

T he journey humankind took from a superstitious to a scientific understanding of the physical world was a long one. The Renaissance was a critical period in the course of this journey, as scientists began developing not just a more enlightened view of the world, but also principles and methods that would guide future generations in expanding their scientific knowledge. At the same time, Renaissance inventors figured out new ways to harness the power of the physical world to vastly increase the capacity for human accomplishment.

This period of science and invention does not solely consist of facts and formulas. It is also a story about personalities with the inspiration and courage to look outside the narrow scope of the established body of knowledge. At the time, this curiosity was often considered bold to the point of defiance, and could carry the risk of severe punishment. This type of conflict adds drama to the story of Renaissance scientists and inventors, and makes their achievements all the more remarkable.

The scientific revolution of the 15th-17th centuries was not just a series of isolated breakthroughs, but a clear change in the method and adventurousness of scientific thinking. As a result, science became a distinct discipline, after having been considered up to that point as simply an offshoot of philosophy. Consistent with this redefinition, science became more concerned with understanding how things worked than with debating why they worked the way they did.

This concept was revolutionary in that it challenged two established orders. One was the authority of the Roman Catholic Church, which was already going through a period of upheaval with the Protestant Reformation. The scientific revolution also took aim at the body of scientific knowledge that had been established by classical Greek thinkers nearly 2,000 years earlier, and which had been more or less universally accepted since.

This movement was also revolutionary in its scope, as it swept across several disciplines of science, including astronomy, physics, chemistry, anatomy, medicine, and biology. All these fields saw new theories that were usually argued over and, often, subsequently refuted and refined. The scientists who advanced these theories may have been persecuted in their own time, only to be celebrated and respected from the perspective of history. The process was neither easy for the individuals leading the scientific revolution nor universally welcomed by a society that frequently balked at proposed new ways of thinking about the world. In the end, however, science was forever changed. Man gained a new empowerment to try to affect the physical world and use it to his advantage.

Each of the fields listed above can trace its modern roots back to the scientific revolution, and this is especially true with the field of astronomy. One indication of how much astronomy changed during the scientific revolution is that when the period began, astronomy was closely related to what is now known as astrology. The movements of stars and planets were tracked to some degree, but largely as the basis for predicting the futures of leading citizens rather than to foster an understanding of the forces behind those movements. Indeed, one of the scientific revolutions earliest major figures, Copernicus, got his start assisting with the production of astrological forecasts. However, as he tracked the movement of the heavenly bodies, Copernicus increasingly turned his attention to formulating an explanation for those movements. This ultimately led to his advancement of the heliocentric theory, which held that the Sun rather than Earth was at the centre of planetary movement.

The ancient astronomer Ptolemy, observing the stars using a quadrant and with the aid of a muse. Photos.com/Thinkstock

The theories of Copernicus were flawed, but they created a foundation for subsequent improvement and advancement. Tycho Brahe, who followed Copernicus, was sparked toward an interest in astronomy when, as a young boy, he witnessed an eclipse of the Sun. It is significant that Brahes career should start with witnessing an astronomical event, since his major contribution to the field was the vast collection of precise celestial observations he made in the latter half of the 16th century. These observations led Brahe to the conclusion that the Copernican model of the universe was often inaccurate. Brahe himself never came up with a fully satisfactory model, but his carefully documented observations created a wealth of data for future astronomers to analyze.

One beneficiary of Brahes work was Johannes Kepler, who had been invited to work with Brahe and inherited his mentors rich catalogue of planetary observations. Ultimately, Kepler discovered three important laws of planetary movement, including the assertion that the planets orbits followed an elliptical course around the Sun. As he worked toward understanding the dynamics driving the movement of planets, Kepler helped lay the groundwork for the later understanding of gravity. Because of this and his writings on the behaviour of light, Kepler is a significant figure in the history of physics as well as astronomy.