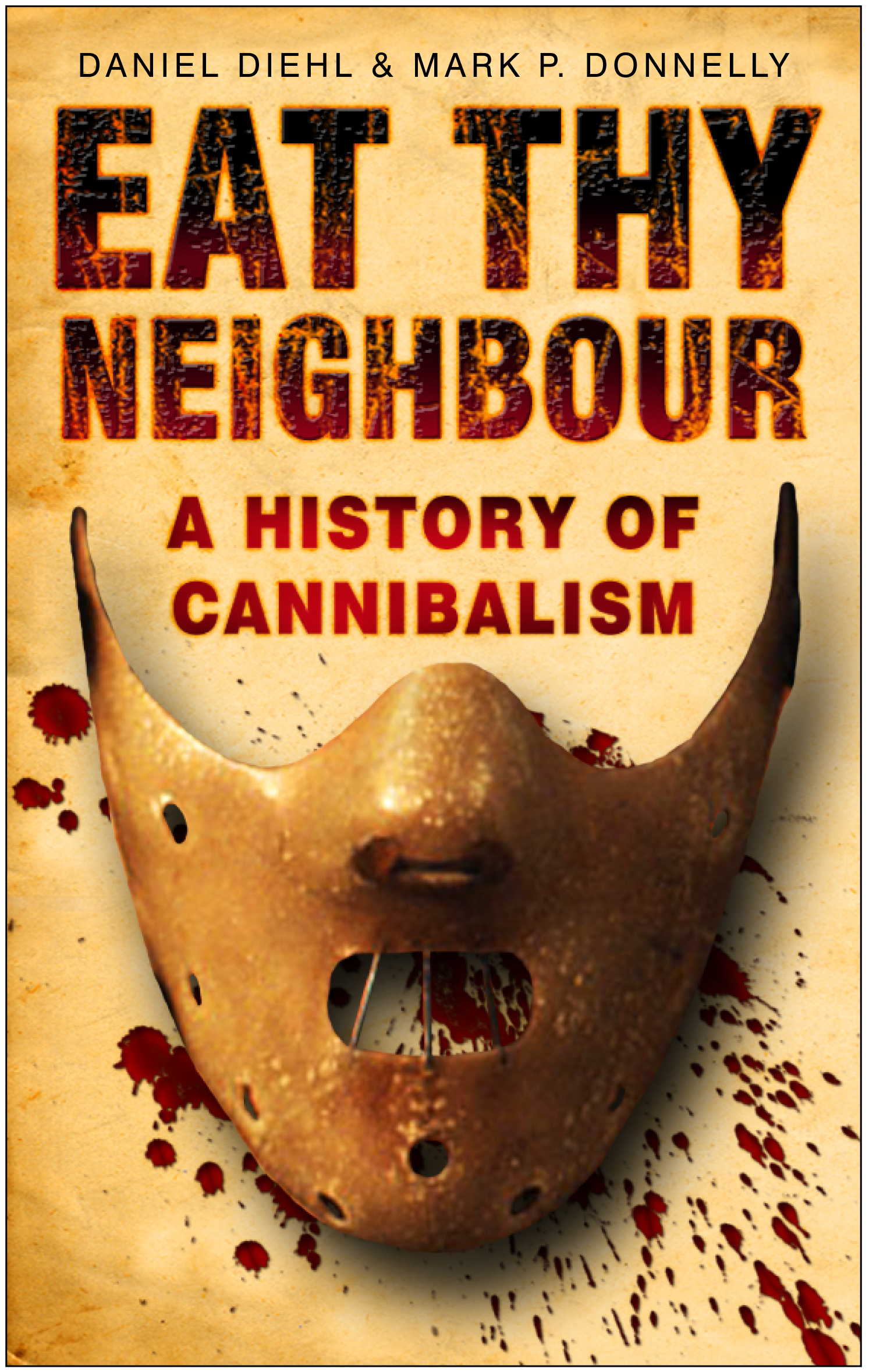

EAT

THY NEIGHBOUR

EAT

THY NEIGHBOUR

A HISTORY OF

CANNIBALISM

MARK P. DONNELLY AND DANIEL DIEHL

First published in 2006 by Sutton Publishing Limited

This revised edition first published in 2008

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

Daniel Diehl and Mark P. Donnelly, 2006, 2008, 2012

Daniel Diehl and Mark P. Donnelly have asserted the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8677 2

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8676 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

Both D ANIEL D IEHL and M ARK P. D ONNELLY are authors, screenwriters and historians. Over the last decade, they have collaborated to create nearly one hundred hours of documentary television programming and have co-authored ten books, including Tales from the Tower of London. Their next book, The Big Book of Pain focuses on the history of torture and corporal punishment.

All spirits are enslaved that serve things evil.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Contents

12. From Russia with Hate: Andr Chikatilo (197890)

Index

Acknowledgements

T he authors would like to thank Christopher Feeney, our editor at Sutton Publishing, for his continued support of our work. A special thanks to Martin Smith, author of River of Blood, for helping us find some amazingly obscure dates and places. Thanks also to Matt Loughran for leading us to the Monty Python sketch, and to our photo researcher Peter Gethin.

PART ONE

C ULTURAL

C ANNIBALISM

One

A Word of Warning: Cannibalism in Myth, Legend, Folklore and Fiction

H umanitys morbid fascination with cannibalism dates from well before the dawn of recorded history. Long before anthropologists and archaeologists found irrefutable evidence of early mans taste for human flesh the knowledge that human beings engaged in cannibalism was already embedded deep in our collective psyche. This inherent knowledge was incorporated into some of our earliest stories and handed down from generation to generation, probably as cautionary tales intended to warn listeners that there were some forms of behaviour that really must be avoided. But if cannibalism was too frightening and too alien for humans to contemplate, who then was it that might engage in such horrific behaviour and still escape the censure of law and social mores? It was, of course, the gods. Cruel, petty and pernicious, the ancient gods served not only as a source of awe and wonder, but provided a vast storehouse of cautionary tales meant to instruct mere mortals as to which behavioural patterns were best left to those who were ultimately above the law.

In the earliest Greek legends the god Cronos (better known as Saturn) was a member of an ancient race of violent and warlike giants called Titans: Cronos was, in fact, the son of Uranus (Heaven) and Gaea (Earth). Despite this enviable pedigree, Cronos was even more cruel and paranoid than the majority of his race. It was widely believed that he devoured five of his offspring in succession because he had been warned that one of them would eventually usurp his power. Obviously the story had a happy ending. Cronos long-suffering wife (and sister) Rhea hid their sixth child none other than Zeus so that he could grow up in one piece and sort out his dads little problem. Rather than simply kill Cronos, Zeus fed him an emetic that caused him to vomit up the rest of the kids who, amazingly, seemed none the worse for the experience.

A similarly gruesome Greek legend, and one with a far more cautionary element, tells the story of poor Pelops, who was murdered and cooked by his father, Tantalus, who thought he was such a clever fellow that he could serve human flesh to the gods and they would never know what it was. Obviously Tantalus was not as sharp as he thought he was, and the gods caught on to the ruse. Tantalus was properly punished and Pelops restored to life after his butchered body was returned to the cauldron in which it had been cooked. All a little silly, maybe, but even in the days of myth and legend cannibalism was seen to bring about serious repercussions. It also made a cracking good storyline, which was used again and again by classical Greek storytellers who had less interest in appeasing the gods than appeasing their audience. When the blind poet Homer wrote his immortal works, the Iliad and the Odyssey in the seventh century BC , he would have been hard pressed not to have included at least one story about someone who ate someone. In this case, a gigantic Cyclops named Polyphemus threatens Ulysses and his crew, devouring several of them before Ulysses outwits him, puts out his single eye and escapes.

Tragically, even in the civilised world of the classical Greeks, the phenomenon of cannibalism was not unknown in the real world. In the religious cult dedicated to the worship of the drunken, half-mad god Dionysus, the annual wine-fuelled revels frequently got far enough out of hand for crazed bands of female acolytes to attack young boys dressed as their god, tear them limb from limb and eat them raw. More than once the celebrants became completely demented and roamed the countryside, killing and eating any man who came within grabbing distance. To their credit, the Greeks were embarrassed by these unsavoury events, but stamping them out proved more than a little problematic. Still, cannibalism in general was seen as an awful thing and charges of consuming human flesh were often levelled against foreigners as an expedient way to make them look like barbarians. Such accusations were a device that would be used by successive societies for thousands of years to come.

At least one Greek, the historian Herodotus, was a little more understanding when describing the beliefs and practices among non-Greek societies. In the fifth century BC , Herodotus wrote his Histories, in which he described a variety of cultures, both real and imagined. In describing a people he called Issedones who, he claimed, lived south of the Ural Mountains, Herodotus said, When a mans father dies, his kinsmen bring beasts of the flock to his house as a sacrificial offering. The sheep and the body of the father of their host are cut [up] and the two sorts of meat are mixed together, served and eaten.

Herodotus tells a similar story about an Indo-European people known as Padaens who had an even more direct approach to cannibalism, not waiting until the soon-to-be-dead had shuffled off the mortal coil before consigning them to the pot. He wrote,... when a man falls sick, his closest companions kill him because, as they put it, their meat would be spoilt if he were allowed to waste away with disease. The invalid, in these circumstances, protests that there is nothing the matter with him but to no purpose. There seemed to have been a sexually specific aspect to this practice of the Padaens, because Herodotus insisted that if the sufferer was a woman it was her female friends who dispatched and devoured her and, likewise, males were eaten only by other males. While it all sounds a bit Monty Python, the Padaens were eventually identified as the Birhors, who did, indeed, kill and eat their dying. However, they insisted that it was only the immediate family who engaged in this peculiar rite because inviting non-family members to the memorial feast would have been sacrilegious in the extreme. This is a practice which is known to anthropologists as endocannibalism and is a concept which we will revisit in greater detail in chapter three.

PART ONE

PART ONE