F or my son,

D avid S immons- D uffin

C ontents

After I had made a first draft of this book, I actively sought the reaction of many musicians from a variety of backgrounds. Some are specialists on various tuning systems; others knew only equal temperament. Some are experienced in historical performance; others have made their careers as modern musicians. All are wonderful and thoughtful performers or music lovers whom I know and am fortunate enough to be able to importune in this way. Their criticisms, arguments, comments, questions, corrections, musings, and additional examples have contributed enormously to the book in its final form.

Among keyboard specialists, first of all, I must thank Bradley Lehman, Christopher Stembridge, Byron Schenkman, Willard Martin, Steven Lubin, Dana Gooley, David Breitman, and Peter Bennett. Wind players who read and commented include Debra Nagy, Bruce Haynes, and Ardal Powell. String players include David Douglass, Robert Mealy, Mary Springfels, Christina Babich, David Miller, Fred Fehleisen, Alan Harrell, Merry Peckham, and Peter Salaff. Physicists, critics, family members, and others with valuable insights include Herbert W. Myers, Cyrus Taylor, Donald Rosenberg, Paul Rapoport, Selena Simmons-Duffin, Jacalyn Duffin, and David Wolfe. I am grateful to them all for their constructive criticisms but, most of all, for their enthusiasm for the book and its message.

My wife, Beverly Simmons, too, contributed her usual expert mix of copyediting and cheerleading and, once again, tolerated my frequent distraction as I immersed myself in the book. She also provided indispensable assistance in obtaining many of the images that help make the book so vivid.

Thanks are due also to Philip Neuman for his inimitable cartoons. I had Phils vision of the musical world in mind from the start, and I hope his contributions will help make the books contents even more memorable.

I am grateful also to several people who assisted in various ways in procuring information or materials for the book: Joanna Ball, Carol Lynn Ward Bamford, Jeremy Barande, Manuel Op de Coul, E. Michael and Patricia Frederick, Cara Gilgenbach, Rebecca Harris-Warrick, Carl Mariani, Sally Pagan, Jeffrey Quick, Roger Savage, Kenneth Slowik, Gary Sturm, Stephen Toombs, Daniel Zager, and Michael Zarky.

I would also like to acknowledge a debt to The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. While this book is about tuning, the biographical sketches contained herein are intended as background, to help set that central discussion into some kind of personal and historical context. No one can do work in musical biography these days without consulting The New Grove and, indeed, many of my sketches are indebted to its articles. The reader is referred to them for further information.

I am grateful to W. W. Norton & Company for getting excited about a project that must have seemed completely off the wall when it first arrived. In particular, I would like to thank my editor, Maribeth Anderson Payne, her assistants Courtney Fitch and Graham Norwood, along with Nancy Palmquist, Don Rifkin, Neil Hoos, Anna Oler, Sue Llewellyn, and a host of other professionals who helped make this book what it is.

Finally, the one person I have omitted from the list of readers above was, in fact, the first person to read a draft hot off the press from my computer: my son, David Simmons-Duffin. He is also the only person to have afterward requested a later version so he could see what changes I had made. As an adolescent, devoted music listener, and novice violinist, David was already noticing and asking about temperaments, and reading Easley Blackwoods daunting Structure of Recognizable Diatonic Tunings with pleasure and profit. A few years later, as a physicist, avid amateur musician, and earliest reader of this book, he had many comments that were exceptionally helpful in clarifying my presentation of the material to a nonspecialist audience, in refining the technical language (though any shortcomings that remain are my own responsibility), and in improving the logic of my argument. One of his first questions to me after reading it, however, was, Dad, who is this for? I paused and then replied, Its for everyone who performs or cares about music. That was true, but only partially so. The pause was because I really wrote it for Davidfor someone who I knew could be persuaded by the evidence and who would genuinely care about the results. I hope that will be true of many readers, but David was my archetype, and so it is to him that this book is affectionately dedicated.

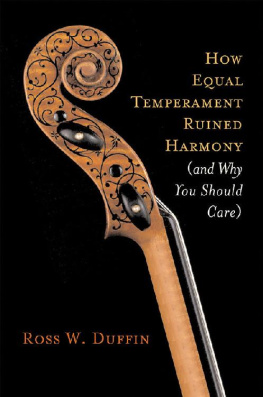

H ow

E qual T emperament

R uined H armony

One must remember that the voluminous literature about tuning systems in the past comes from people who were of no musical importance.

E. MICHAEL FREDERICK, Some Thoughts on Equal Temperament Tuning

THE AUDIENCE HUNG on every word uttered by the silvermaned maestro. As he spoke, heads nodded slowly all around the room in silent acknowledgment of the fundamental truths he imparted. For eighteen years Christoph von Dohnnyi had led the Cleveland Orchestra, one of the premier ensembles in the world, and now he was reflecting on his tenure in a kind of exit interview with music critic Donald Rosenberg before four hundredodd friends and admirers. Having recently returned from a final performance at Carnegie Hall, Dohnnyi at one point mused about a frustration in the preparation of Beethovens Ninth Symphony for that program. No recording exists of his remarks in that January twilight in 2002, but my recollection is that he said the following:

The symphony begins with about two minutes of a D-minor chord. But after that D minor comes a striking shift to B-flat major. In rehearsal, I just couldnt get that B-flat chord to sound right. I mean, I know what a major third is, and all of the players are consummate professionals, but we tried it over and over and I was never satisfied.

At that moment I knew I had to write this book. Here was one of the great conductors of the world, leader of one of the greatest orchestras in the world, and he didnt understand why this apparently simple shift in harmony from a D-minor to a B -major chord didnt sound right. If he didnt know, then it seemed logical to assume that most musicians wouldnt know. But I think I know. Its all wrapped up in recent evolutions in musical performance and teaching, the result of decades of delusion, convenience, ignorance, conditioning, and oblivion.

-major chord didnt sound right. If he didnt know, then it seemed logical to assume that most musicians wouldnt know. But I think I know. Its all wrapped up in recent evolutions in musical performance and teaching, the result of decades of delusion, convenience, ignorance, conditioning, and oblivion.

Does that sound harsh? Stay with me, gentle reader. It is not a reflection on the mastery of superb musicians like Christoph von Dohnnyi, but by the end of this book, I hope youll see that, contrary to the old adage, what most musicians dont know has hurt them, along with injuring the music they make.

Next page

-major chord didnt sound right. If he didnt know, then it seemed logical to assume that most musicians wouldnt know. But I think I know. Its all wrapped up in recent evolutions in musical performance and teaching, the result of decades of delusion, convenience, ignorance, conditioning, and oblivion.

-major chord didnt sound right. If he didnt know, then it seemed logical to assume that most musicians wouldnt know. But I think I know. Its all wrapped up in recent evolutions in musical performance and teaching, the result of decades of delusion, convenience, ignorance, conditioning, and oblivion.