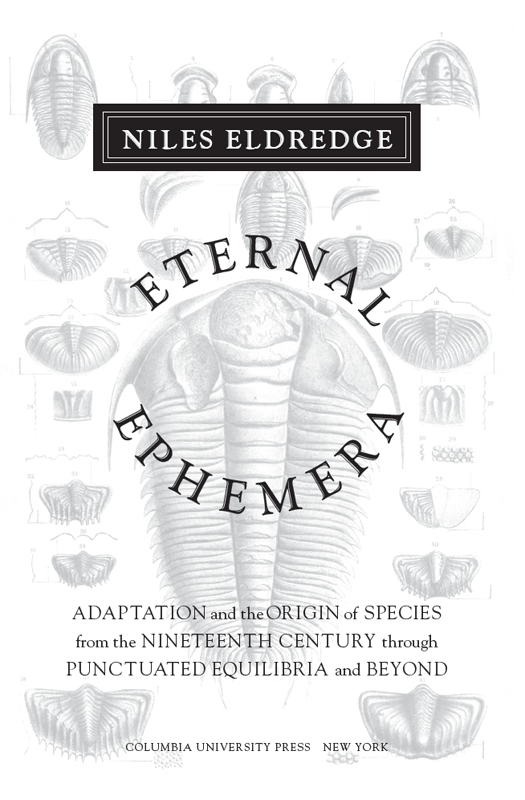

ETERNAL EPHEMERA

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2015 Niles Eldredge

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52675-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Eldredge, Niles.

Eternal Ephemera: Adaptation and the Origin of Species from the Nineteenth Century through Punctuated Equilibria and Beyond / Niles Eldredge.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-15316-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-52675-3 (e-book)

1. Darwin, Charles, 18091882. On the origin of species. 2. Punctuated equilibrium (Evolution) 3. Evolution (Biology)Philosophy. 4. Emergence (Philosophy) I. Title.

QH398.E43 2015

576.8'2dc23

2014022519

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

FRONTISPIECE: Southern South America, showing locales important to Darwin on the Beagle voyage, 18321835. (Artwork by Network Graphics)

COVER IMAGE

Plate 3 from Joachim Barrande, Systme silurien du centre de la Bohme (1852).

COVER DESIGN

Lisa Hamm

References to Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing.

Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

To Michelle, who has given me everything

Like the Shadows of the Clouds in a Summers Day

In this vast host of living beings, which all start into existence, vanish, and are renewed, in swift succession, like the shadows of the clouds in a summers day, each species has its peculiar form, structure, properties, and habits, adapted to its situation, which serve to distinguish it from every other species; and each individual has its destined purpose in the economy of nature. Individuals appear and disappear in rapid succession upon the earth, and entire species of animals have their limited duration, which is but a moment, compared with the antiquity of the globe. Numberless species, and even entire genera and tribes of animals, the links which once connected the existing races, have long since begun and finished their career.

ROBERT E. GRANT, INAUGURAL ADDRESS, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, 1828

MENTOR TO CHARLES DARWIN, EDINBURGH, 1827

CONTENTS

R obert Grant left little iron-clad evidence that he was the radical, pro-Lamarckian thinker that in fact he was. Were it not for Charles Darwins brief passage describing Grants outburst as they were walking together one day, few would have placed Grant among the small but influential group known as the Edinburgh Lamarckians. Gentlemen did not often publicly express their pro-evolutionary views in Great Britain in the 1820s.

The excerpt from Grants inaugural address to the public on the occasion of his being appointed professor at the University of London, used as the epigraph to this book, is the closest thing to pure poetry in the annals of evolutionary biology. Thanks to Darwin, we know of Grants evolutionary convictions, so when we read his words, there can be no doubt of their true meaning.

Individual organisms, and indeed even species, though they tend to persist little changed over millions of years, are in the end evanescent like the shadows of the clouds in a summers day. And yet they are all linked together in ancient skeins of lifeindividuals, species, and larger groups, many of which are lost in the deep annals of time. Together they are the eternal ephemera, whose origins and extinctions, and their adaptively forged roles in the economy of nature, are the original, and still continuing, subject matter of evolutionary biology.

This is the story of the search for rational, non-miraculous understanding of these eternal ephemera. It is, at the same time, an exploration of my own struggles with these issues. I have learned only late in my career, decades after punctuated equilibria and related themes, of the long-lost connections to my own intellectual forbears of the early nineteenth century. The evolution of evolution, as it were.

I n the acknowledgments to his magnum opus, The Rise of Anthropological Theory, Marvin Harris said that when an author has completed his book, it would seem a simple task to thank those who helped him in its preparation. In actuality the task is not an easy one at all.

Very true. Acknowledging everyone who played a role in showing me the way all along is nearly impossible. But Ill give it a shot.

I was an undergraduate at Columbia College from 1961 to 1965. I decided as a freshman to remain in academic life. Initially, I thought that Greek and Latin would be an appropriate major for me. But I also met Michelle Wycoff as a freshman; we were married in 1964, and she has been the major influence in my life all along the way. She has been indispensable, in particular with her help and encouragement on this book, which she has copyedited and made readable. I can also say that she is very glad that I am finally finished with it! Thanks, babeI love you so much!

Michelle knew several of the Anthropology Department faculty membersamong them Marvin Harris. She often baby-sat for the Harris kids, and I got to know the family right away. In those days I thought anthropology was more a matter of Louis Leakeystyle hominid fossil hunting than Margaret Meadstyle cultural anthropology. (She was also at Columbia and the American Museum and always very nice to me. Marvin, of course, was a cultural anthropologistthough hardly in Margarets style!) I started taking anthropology courses and, under Marvins aegis, joined a small group of greenhorn undergraduates in the summer of 1963. We lived in and around Arembepe, Brazil, in the days before paved streets, running water, or electricity, save on two special feast days each year.

In many ways that Brazilian experience in 1963 was one of the most important formative experiences of my lifeand certainly of my subsequent career in evolutionary biology. Among many other things, I decided while there that my future path would lie more along the fossils that studded the sandstone reef at Arembepe than in pestering people about their private lives in my baby-talk Portuguese.

Returning to New York that fall, I enrolled in a paleontology class taught by John Imbrie. Imbries courses, plus the summer (1964) research opportunity under paleontologist Roger L. Batten at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), sealed the deal: paleontology was it! By the end of my college sojourn, I eventually amassed more credits in geology than in anthropology.

I stayed for graduate school in the Department of Geology from 1965 to 1969. My main mentors/advisors were Roger Batten and the great Norman D. Newell, whom I had met only in passing in the corridors of the AMNH. In those days, American Museum curators often had dual appointments at Columbia, and Roger and Norman were no exception. In the end, Norman became my official advisor.