CONTENTS

To the five hundred colored schoolchildren

of Jacksonville, Florida, who kept singing

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

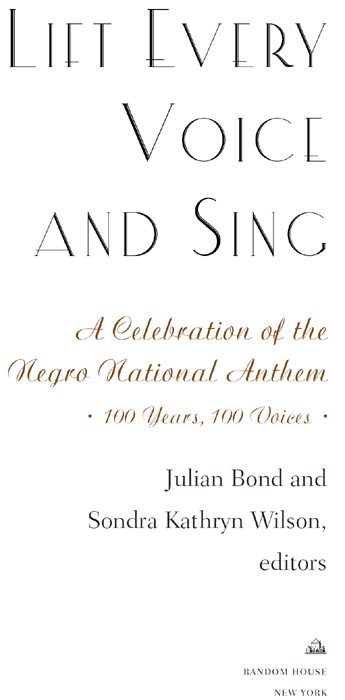

P roducing Lift Every Voice and Sing: A Celebration of the Negro National Anthem has been an inspiring and highly rewarding undertaking.

This book represents the efficacy of consummate publishing professionals: Manie Barron, Melody Guy, and Benjamin Dreyer of Random House. We are exceptionally grateful to them for their spirited efforts, particularly when time was such a critically vital factor; it was imperative that the books release correspond with the centennial anniversary of Lift Every Voice and Sing. Manie Barron embraced this project when it was merely an undeveloped proposal. We benefited greatly from his perceptions and sound judgment, which enabled us to truly envision the book. Melody Guy brought a harmonious commitment, accompanied by highly proficient skills, that infused us with the necessary energy to meet the difficult challenges that come with bringing together one hundred voices. Our morale was invariably lifted by her diplomacy and commonsense approach in bringing together individuals who held varying opinions. We were extremely confident in the meticulous editorial skills of Benjamin Dreyer, on whom we relied to produce a work wholly commensurate with our vision down to the last detail.

We were truly blessed to have the wide-ranging assistance of Mildred Bond Roxborough, who became involved in this project in its earliest stages. Her archives proved invaluable as a source for contacting many of the contributors to this book.

Evelyn Parker acted as consulting editor from the beginning of this project. She good-naturedly and with flexibility proffered her time. We will never forget the care and enthusiasm she expressed throughout this endeavor.

We are especially grateful to the mother-and-daughter team of Julie Baker and Angela Baker, of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Serving as liaisons between the editors and the contributors, they never doubted that this objective would be achieved. Its going to be a great book! they told us in almost every conversation. We were comforted by their unwavering devotion and ardor.

Our frequent exchanges with Armstrong Williams, from whom we sought advice, were helpful in providing contact information for certain potential contributors; he became one of the projects chief advocates. We came to rely on his insights and his marvelous sense of humor to help the process along in a smooth and timely manner.

Gamilah-L. Shabazz and Nancie Teeter McPhail were helpful in processing information. We will be forever grateful for the sensitivity and compassion they displayed throughout.

We are profoundly indebted to the contributors presented here, who have lifted their voices to celebrate the centennial of Lift Every Voice and Sing. It is their essays that help relate the profound story of a revered song that has been deeply ingrained in the black experience for generations. It is impossible to find adequate words to convey the significance that each of these individuals has had upon the completion of this book.

We are especially grateful to Ollie Jewel Sims Okala for sharing James Weldon Johnsons correspondence regarding Lift Every Voice and Sing. We also appreciate the memories she shared of her conversations with James Weldon Johnson about the song. Her help and support have been invaluable to this book.

The pictorial story of African Americans presented here was accomplished with the enthusiastic suggestions and abiding support of Charles L. Blockson, Chris Griffith, Howard Dodson and his staff at Schomburg Center, and Ernie Paniccioli.

We deeply appreciate the generosity of the late Jacob Lawrence, who produced his vision of Lift Every Voice and Sing in art form for this book.

This book also represents the assistance of numerous other persons: Yvonne Benjamin, Herb Boyd, ALelia Bundles, Lee Daniels, Walter O. Evans, Victoria Horsford, Jennifer Spingarn Huggins, Martin L. Kilson, Honor Spingarn Tranum, Jane White Viazzi, and Craig Stevens Wilson. We benefited from the assistance of countless others; their efforts will not be forgotten.

Finally, we thank our families, who circled us with their love and enthusiasm throughout this process.

INTRODUCTION

I got my first lineLift every voice and sing. Not a startling line, but I worked along grinding out the next five. When, near the end of the first stanza, there came to me the lines

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us

the spirit of the poem had taken hold of me. I finished the stanza and turned it over to Rosamond. In composing the two other stanzas I did not use pen and paper. While my brother worked at his musical setting I paced back and forth on the front porch, repeating the lines over and over to myself, going through all of the agony and ecstasy of creating. As I worked through the opening and middle lines of the last stanza:

God of our weary years,

God of our silent tears,

Thou who hast brought us thus far on our way;

Thou who hast by Thy might

Led us into the light.

Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee,

Lest, our hearts, drunk with the wine of the world, we forget

Thee...

I could not keep back the tears, and made no effort to do so. I was experiencing the transports of the poets ecstasy. Feverish ecstasy was followed by that contentmentthat sense of serene joywhich makes artistic creation the most complete of all human experiences. When I had put the last stanza down on paper I at once recognized the Kiplingesque touch in the two longer lines quoted above; but I knew that in the stanza the American Negro was, historically and spiritually, immanent; and I decided to let it stand as it was written.*

JAMES WELDON JOHNSON

*James Weldon Johnson, Along This Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson. New York: Viking Press, 1933, pp. 154155.

It is wondrous and hardly explicable to many how James Weldon Johnson could have written such spiritually enriching lyrics in 1900 despite the restraints ordained by Jim Crow laws, despite frenzied lynchings and mob violence, despite the fact that white America had established an educational system teeming with stereotypes that had misrepresented and malformed virtually every external view of African American life. Underpinning these sweeping injustices was the Supreme Courts ruling in the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson case four years before Lift Every Voice and Sing was written in 1900. This decision meant that state laws requiring separate but equal facilities for African Americans were a reasonable use of state powers. Further, The object of the [Fourteenth] Amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the laws, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based on color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either.

Lerone Bennett, Jr., Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America. New York: Penguin Books, 1988, p. 267.

Next page