Cadava Eduardo - When I Was a Photographer

Here you can read online Cadava Eduardo - When I Was a Photographer full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Cambridge;Massachusetts, year: 2016;2015, publisher: The MIT Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:When I Was a Photographer

- Author:

- Publisher:The MIT Press

- Genre:

- Year:2016;2015

- City:Cambridge;Massachusetts

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

When I Was a Photographer: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "When I Was a Photographer" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

When I Was a Photographer — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "When I Was a Photographer" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

When I Was

a Photographer

When I Was

a Photographer

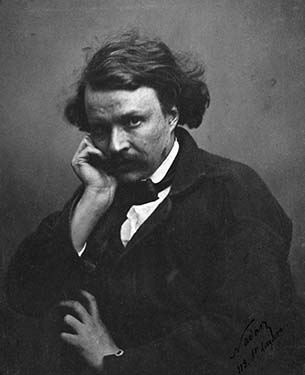

Flix Nadar

Translated By

Eduardo Cadava and

Liana Theodoratou

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2015 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Originally published in French as Quand jtais photographe by E. Flammarion, Paris, in 1900.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nadar, Flix, 18201910.

[Quand jtais photographe. English]

When I was a photographer / Flix Nadar ; translated

by Eduardo Cadava and Liana Theodoratou.

p. cm.

Translation of: Quand jtais photographe.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-02945-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-262-33072-5 (retail e-book)

1. Nadar, Flix, 18201910Anecdotes.

2. PhotographyFranceAnecdotes.

3. PhotographersFranceAnecdotes.

I. Cadava, Eduardo. II. Theodoratou, Liana.

III. Title.

TR149.N2713 2015

770.92dc23

2015001894

Acknowledgments

One of the great pleasures of finishing a project, and especially one that has taken a number of years to accomplish, is the opportunity to extend a gesture of gratitude to all the friends, colleagues, and supporters who made its realization possible.

Nevertheless, like a translation that seeks to remember its debts to the original it inevitably transformseven as it must acknowledge its incapacity to preserve everythingthe memory of acknowledgments can never remember well enough the numerous gifts to be acknowledged. Even if we can never entirely express the gratitude and indebtedness from which this work has been born, though, we wish to acknowledge the wonderful community that has enabled it to come to light.

We first want to thank Roger Conover, executive editor at the MIT Press, for embracing the possibility of translating Nadars memoirs in the first place and for his enthusiastic support throughout the project. His consistent patience, kindness, and scrupulousness have been greatly appreciated and, indeed, this project would not have been realized without his sense of its importance and his dedication to it. We wish to thank Matthew Abbate, senior editor, who was particularly helpful and supportive in the later stages of the books production and who so kindly helped with our index. We thank Margarita Encomienda, senior designer, for her lovely design of the book, and Justin Kehoe, assistant acquisitions editor, for his early help with the manuscripts preparation.

We are grateful to the many friends and colleagues who expressed an interest in this project and who talked with us about it, often in wildly different contexts. We especially wish to thank Branka Arsic, Ariella Azoulay, Jennifer Bajorek, Melina Blcazar, Benjamin Buchloh, Esther Cohen, Andrew Dechet, Marie de Testa, Hannah Feldman, David Ferris, Mia Fineman, Hal Foster, Nathalie Froloff, Carlos Gollonet Carnicero, Anjuli Gunaratne, Michael Jennings, Branden Joseph, Tom Levin, Aaron Levy, Mauricio Lissovsky, Susan Meiselas, Rosalind Morris, Elena Peregrina, Avital Ronell, Lidia Santarelli, Fazal Sheikh, Kaja Silverman, Joel Smith, Federica Soletta, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Peter Szendy, and David Wills.

We would like to thank Zakir Paul for his help with the Professional Secret vignette, Lidia Santarelli for her assistance with part of the Primitives of Photography section, and David Wills for his generous and precise help with particularly intransigent passages. We especially wish to thank Gillian Beaumont, who graciously read through our entire manuscript and made innumerable small suggestions that helped make the translation more graceful and elegant throughout. We are grateful to the kindness of each of these richly inventive translators.

We wish to thank Gwen Roginsky from the Editorial Depart-ment of the Metropolitan Museum of Art for kindly permitting us to reproduce part of the wonderfully helpful Chronology that was prepared by Maria Morris Hambourg and others for the Museums 1995 catalog Nadar. We also thank Grey Room and the MIT Press for allowing us to incorporate the first, shorter version of Nadars Photographopolispublished by them in 2012into this editions longer introduction.

We thank everyone who helped make this book possible. Its existence confirms that nothing can ever be produced alone, and this is particularly fitting, it seems to us, in a project about a photographer and writer whose fame is so associated with the richness of his friendships and relations. Like Nadar, we have been blessed with such friendships and relations and we owe a felt debt for the remarkable and sustaining world that they enable us to inhabit.

Introduction: Nadars Photographopolis

EDUARDO CADAVA

The world itself has taken on a photographic face; it can be photographed because it strives to be completely reducible to the spatial continuum that yields to snapshots. What the photographs by their sheer accumulation attempt to banish is the recollection of death, which is part and parcel of every memory-image the world has become a photographable present, and the photographed present has been entirely eternalized. Seemingly ripped from the clutch of death, in reality it has succumbed to it all the more.

Siegfried Kracauer, Photography (1927)

I

In a fragment belonging to the posthumous text On the Concept of Historya fragment entitled The Dialectical Image that cites a passage from Andr MonglondWalter Benjamin writes:

If one looks upon history as a text, then what is valuable in it is what a recent author says of literary texts: the past has left in them images which can be compared to those held fast in a light sensitive plate. Only the future has developers at its disposal that are strong enough to allow the image to come to light in all its details. Many a page in Marivaux or Rousseau reveals a secret sense, which the contemporary reader cannot have deciphered completely. This historical method is a philological one, whose foundation is the book of life. To read what was never written, says Hofmannsthal. The reader to be thought of here is the true historian.

Although Monglond suggests that history can be likened to the process wherein a photograph is produced in order to hold a memory fast, Benjamin complicates the comparison by introducing a series of comparisons into it. As David Ferris notes, if we include the opening conditional phraseIf one looks upon history as a textthe sentence makes three comparisons: The first, hypothetical, makes history and a text equivalent to one another. The second compares a text to a photographic plate. The third, by accepting the terms of the first hypothetical comparison, would offer knowledge of the initial subject of this whole sequence: history. [T]he logic enacted by these comparisons, he goes on to suggest, takes the form of a syllogism that can be expressed as follows: if history is comparable to a text and a text is comparable to a photographic plate, then history is comparable to that same photographic plate.

But what is properly historical here only reveals itself to a future generation capable of recognizing it; that is, a generation possessing developers strong enough to fix an image never seen before. This is what is so difficult to understand in Benjamins account: because the image that emerges was already there but could not be seen either when it was taken or in the intervening time, these images offer different degrees of detail. This is why there can be no image that does not involve a deviation or swerve. In the second entry to Convolute N of his

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «When I Was a Photographer»

Look at similar books to When I Was a Photographer. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book When I Was a Photographer and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.