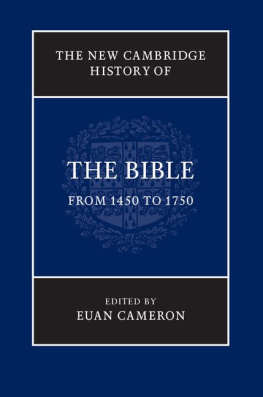

Cameron - Enchanted Europe: superstition, reason and religion, 1250-1750

Here you can read online Cameron - Enchanted Europe: superstition, reason and religion, 1250-1750 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Oxford, year: 2012;2010, publisher: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Enchanted Europe: superstition, reason and religion, 1250-1750: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Enchanted Europe: superstition, reason and religion, 1250-1750" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Enchanted Europe: superstition, reason and religion, 1250-1750 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Enchanted Europe: superstition, reason and religion, 1250-1750" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

ENCHANTED EUROPE

SUPERSTITION, REASON, AND RELIGION, 12501750

EUAN CAMERON

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Euan Cameron 2010

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2009939955

Typeset by Laserwords Private Limited, Chennai, India

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham,

Wiltshire

ISBN 9780199257829

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Ruth, again

Although this book has been slightly less than two years in writing, its origins go back much further. After completing The European Reformation (1991) I soon realized that the challenge of understanding popular religion in the pre-Reformation and Reformation worlds required more extensive research and reflection than the few pages that were assigned to it in the earlier book. Some preliminary research and a few experimental conference papers later, it became clear that a specific genre of religious writing, the theological analysis and critique of superstition, offered a fruitful and interesting territory to explore. Historians who sought to unearth from refractory and difficult sources the putative reality of popular belief habitually left on the editing-room floor many pages of unwanted theological reflection. This processing, this analysis, this effort to make doctrinal sense of what superstition was and to say why people ought not to engage in it, yielded all sorts of fascinating insights, and it forms the heart of this book.

In a long project one incurs many debts of gratitude. One of the earliest and most significant must be to the Leverhulme Trust, which elected me to a research fellowship for 1996/7. That precious academic year of research time launched this book project by making possible the uninterrupted study of difficult texts in a range of languages. Four other book projects then supervened, and required the research on the critique of superstition to be kept on hold, but the project continued. A second major debt is owed to the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, which assisted with my Leverhulme fellowship year and allowed me a further semesters sabbatical leave in the autumn of 2001, vital for shaping the project. Newcastle University Library willingly acquired a set of key microfilm texts for my use and facilitated this work in too many ways to mention.

Union Theological Seminary, its faculty, president and trustees, invited and welcomed me and my family to New York when they asked me to take up the Henry Luce III Chair of Reformation Church History in the summer of 2002. This appointment placed the astonishing theological riches of the Burke Library, at that time the exclusive responsibility of the seminary, at my disposal. Union also, by allowing me a semesters sabbatical leave in the spring of 2008, contributed much-needed time for the completion of the first draft of this book.

Columbia University, by affording me membership of the departments of religion and history and by inviting me to advise students in the doctoral programme, has been similarly gracious and supportive. Since taking responsibility for the Burke Library, Columbia University Libraries have enriched this project in many ways, through additional resources both in paper and electronic form, and through the continuing and ever-valued assistance of the staff of the Columbia Libraries system.

A further stimulus and encouragement to this work came when the Folger Institute, based in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC, invited me to lead a seminar in the fall semester of 2006 on Martin Luther and the sixteenth-century universe. Those ten weeks of energetic discussion on Friday afternoons afforded some of the most fruitful and exciting teaching experiences of my life. The helpfulness and appreciation of the Folger Institute staff made the leading of that seminar a pure joy.

Successive generations of students have by their input and responses shaped this book profoundly. Those who participated in my final-year special subject seminar at Newcastle, and in a related MA programme, required me to refine and order my thoughts and address many theoretical issues. The participants in my popular religion course at Union have again and again brought the breadth and depth of their theological questioning to bear on the material. The sheer commitment, expertise, and diverse interests of the participants in the 2006 Folger Institute seminar played a key role in shaping the ideas that have now emerged: I gratefully acknowledge here the roles of Sara Brooks, Jennifer Clement, Ruth Friedman, Genelle Gertz, Phil Haberkern, Michael Meere, Esther Gilman Richey, Jennifer Waldron, and Jennifer Welsh. Several doctoral students, as they developed their own distinctive and individual projects and perspectives, have contributed more than they know to my own growth, especially Lisa Watson and John Schofield at Newcastle, Susan Greenbaum and John Reynolds at Union, and Matt Pereira, Sarah Raskin, and many others at Columbia University.

Colleagues in all the places where I have worked have been generous with their support and encouragement. I gratefully record the contributions made by many historian colleagues where I have worked, especially Jeremy Boulton at Newcastle and Daisy Machado, John McGuckin, and Robert Somerville here in New York. To all my Union colleagues, faculty and staff, who have watched me try, with limited success, to balance the demands of deanship, seminary teaching, and research, I extend my thanks for their understanding and patience. More specifically, those fellow historians who have talked through the rapid emergence and growth of superstition as a subject distinct from magic and witchcraft have aided me considerably: in the United Kingdom, Robin Briggs, Patrick Collinson, Eamon Duffy, Bruce Gordon, Diarmaid MacCulloch, Peter Marshall, Andrew Pettegree, Richard Rex, and Alison Rowlands; in the United States, Michael D. Bailey, Caroline Walker Bynum, Michelle Gonzalez Maldonado, Nathan Rein, and Amy DeRogatis, from the History of Christianity section of the American Academy of Religion, and Randall Styers. Two expert and gracious readers for Oxford University Press made extremely helpful and constructive suggestions towards the final stages. Working with the astonishingly patient and professional staff of Oxford University Press has been a pleasure as always.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Enchanted Europe: superstition, reason and religion, 1250-1750»

Look at similar books to Enchanted Europe: superstition, reason and religion, 1250-1750. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Enchanted Europe: superstition, reason and religion, 1250-1750 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.