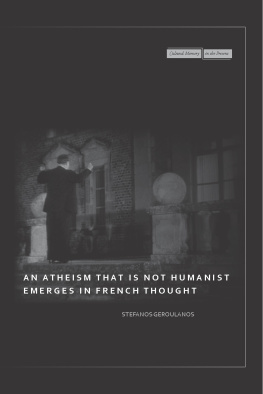

THE END OF THE SOUL

THE END OF THE SOUL

Scientific Modernity, Atheism, and Anthropology in France

Jennifer Michael Hecht

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2003 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-50238-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hecht, Jennifer Michael, 1965

The end of the soul : scientific modernity, atheism, and anthropology in France/Jennifer Michael Hecht.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0231128460 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. AtheismFranceHistory. 2. Religion and scienceFranceHistory. 3. AnthropologyReligious aspectsHistory. 4. AnthropologyFranceHistory. 5. FranceReligion. I. Title.

BL2765.F8 H43 2003

211.8094409034dc21 2002035093

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

To my sister and brother

Many people helped this book come into being. I would first like to thank Robert Owen Paxton, who guided my study of French history when I was a doctoral student at Columbia University, and Nancy Leys Stepan, who introduced me to the history of science there, especially the history of scientific claims about human difference. While I was engaged in the early research for this project in France, Maurice Agulhon at the Collge de France discussed the work with me and brought to my attention a study of French ethnology recently published by Nlia Dias. Nlia and I met in New York a few years later, and since then I have been delighted to share with her our odd familiarity with the same otherwise half-forgotten band. Historian and race theorist Pierre-Andr Taguieff discussed Lapouge with me for several hours on a rainy Paris afternoon and later helped me gain access to the archives in Montpellier. Claude Blanckaert shared his expertise of the Socit danthropologie de Paris and its archives. A small, international crew of scholars had variously decided to take notes in the Muse de lhomme every day and go to Professor Blanckaerts seminar once a week at the Musum dhistoire naturelle, after which he would join us at a caf to drink espresso and wine and argue about Broca. I learned a lot about the mood of nineteenth-century European natural science in those sessions. I would also like to thank the librarians at the Paris Muse de lhomme for their gracious and informed assistance. Claude Blanckaert invited me to take part in the CNRS conference La race: Ides dans les sciences et dans lhistoire in 1993, where my study of Lapouge benefited from participants observations.

Alexander Alland, Atina Grossmann, and Vera Zolberg read parts of the manuscript at various stages and offered helpful comments and much appreciated encouragement. I must also thank the anonymous readers of French Historical Studies, the Journal of the History of Ideas, Isis: Journal of the History of Science Society, and the Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences for their often exceedingly helpful criticism and questions. Similarly heartfelt thanks go to the anonymous reviewers who offered comments on the present work as it made its way to press. After the book was finished, two scholarly events in which I took part offered new things to think about: At the 2001 History of Science Society conference, Ian Dowbiggin, Mike Hawkins, Richard Weikart, and I delivered papers for a session entitled The Life Sciences and the Crisis of Ethics, chaired by Edward Larson. It was good to compare notes from France, England, Germany and the United States. Evelynn Hammondss Race and Science workshop at MIT (February 2002) brought together twenty scholars working on that subject. The lively weekend of talk influenced some of my final thoughts here and redoubled my enthusiasm to share this curious chapter in the history of anthropology.

Thanks to Mary Keller, as always, for all sorts of advice, insight, inspiration, and encouragement. Thanks to Steven Hull for going to the Library of Congress with me so many times while I researched this book, and for many long conversations. Thanks, too, to the Ginocchio family for their camaraderie and hospitality during my several stays in Paris. The support of my parents, Carolyn and Gene, has been inestimable.

I thank my husband, John Chaneski, for his considerable help in preparing the manuscript for print, his ebullient companionship in all things, and his surprising height. Finally, over the years my siblings, Amy Allison and Jamey, read the manuscript in its entirety and in parts and engaged me in my extended reveries on French anthropology, autopsies, and free thought. Theyre also funny. This book is dedicated to them both. Finally, I would like to sample notions from the acknowledgments pages of the first books of my two advisers at Columbia. One noted the role of the Meades pear tree that she could see from her window as she wrote; I am happily reminded to give witness to the stained glass of the Eglise St. Mdard that faced my Paris apartment and to the low red brick and high metal spires of New York City. The others disclaimer seemed so right to me that I am compelled to borrow it: These friends and helpers are in no way responsible, of course, for whatever errors, perversities of judgment, or downright idiosyncrasies may appear in this book. Those belong altogether to the author.

This book is about atheism and its relationship to science, especially the science of peopleof race, gender, class, and nationat the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. I started researching this topic about ten years ago because I read of the existence of a Society of Mutual Autopsy, and I wanted to know more. The French anthropologists that created it dominated the Society of Anthropology of Paris in the last decades of the century and championed an outspoken, overt mixture of science and anticlerical politics. The history of the Society of Anthropology of Paris in this period had been explored in several works, most notably, in French, in several articles by Claude Blanckaert and a book by Nlia Dias and, in English, in an article by Michael Hammond and the dissertations of Joy Harvey and Elizabeth Williams.

By the late nineteenth century, French culture was dominated by the notion that tradition, church, monarchy, and dogma were naturally and inextricably united in a struggle against change, freedom, democracy, and science. The confrontation between science and religion was a constant theme. But before the publication of Darwins Origin of Species in 1859, even most left-wing intellectuals felt that some deistic notion was necessary to account for human existence. Evolutionary theory did not cause anticlericalism or atheism, but it was a great and encouraging windfall for those who were already in opposition to the church. Some forms of anticlericalism reach back before the Revolution, but under Napoleon IIIs Second Empire, political repression and the privileges of the Catholic Church wildly exacerbated the hostility between Catholicism and republicanism. As Theodore Zeldin has put it, Clericalism and anticlericalism became probably the most fundamental cause of division among Frenchmen. Indeed, Zeldin credits the anticlerical passion of this period with the creation of a two-party political system in France: without much agreement on anything else, everyone in France was either for or against the clergy (p. 1027). In this great division, there were several sites of the anticlerical avant-gardeor those who saw themselves as suchand this book is the history of one of them.

Next page