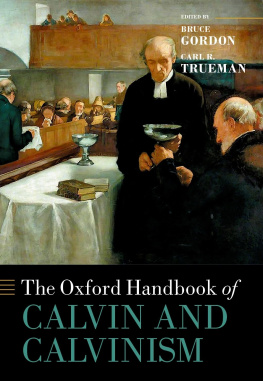

Copyright 2013 D. G. Hart

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Arno Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hart, D. G. (Darryl G.)

Calvinism : a history / D.G. Hart.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-300-14879-4 (hardback)

1. CalvinismHistory.I. Title.

BX9422.5.H37 2013

284'.209dc23

2013003010

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Jim and Nancy Loux

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments

T IS THE SEASON OF Calvinist anniversaries. July 10, 2009 marked the 500th anniversary of John Calvin's birthday, an occasion that prompted the appropriate number of conferences, op-ed pieces, biographies, and anthologies. This year was the 200th anniversary of the founding of Princeton Theological Seminary, a United States institution with an international reputation for teaching and studying Calvinism. Next year will mark the 450th anniversary of the Heidelberg Catechism, a pedagogical device for the Reformed churches in the Palatinate that became a doctrinal standard for Calvinists around the world. We are still over ten years from the 500th anniversary of the start of the Protestant Reformation in Zurich, the first European city to check a religious identity box different from both Lutheranism and Roman Catholicism under Ulrich Zwingli's leadership.

This book is not designed to observe any particular anniversary but it almost coincides with half a millennium of Calvinist developments. It is an audacious undertaking in many respects. Putting so much history in so many places into one relatively small volume runs against the grain of academic history since it requires pronouncements on subjects and eras about which the historian has no professional competency. I am trained as a historian of the United States and have worked generally on subjects since the Civil War. The prospect of writing a paragraph, let alone a section of a chapter, on religious developments in sixteenth-century Poland is almost as scary as bungee jumping. But when an editor at Yale University Press asked me to consider a history of Calvinism that would cover its global dimensions I immediately accepted, maybe because the only legal excitement available to me is one that comes with landing a golf ball on a green surrounded by sand.

Readers will discover soon enough my rationale for organizing material from five different centuries and just as many continents. Finding a single narrative that could do justice to Reformed Protestantism without relying on parochial forms of denominational history was arguably the hardest challenge. But what was not difficult was the fascination that ensued from observing historical circumstances that saw a small group of churches in sixteenth-century Swiss cities gain a following throughout Europe, only to become a global phenomenon after 1600 through colonialism, migration, and missions. Just as the framers of the United States Constitution could not have fathomed that the republic they formed would be engaged 175 years later in a Cold War with Communists in eastern Europe, so John Calvin would never have imagined that Asian Christians in twenty-first-century Seoul, Korea, would identify with the interpretation of Scripture and church structures that he proposed in 1540s Geneva. Indeed, what makes a global history of Calvinism captivating is seeing how accidental and unexpected Reformed Protestant developments were. No leader of the Presbyterian or Reformed churches could have planned the way that Calvinism turned out. Some might even have been disappointed with the outcome. Whatever those expectations, the global history of Calvinism reveals a set of religious institutions caught up in the tumultuous developments of the modern era that saw Europeans (for good and ill) dominate affairs on Planet Earth.

I am grateful for the help and encouragement of many people during the writing of this book. Chief among them is Heather McCallum, my longsuffering editor at Yale, who patiently waited for drafts and provided useful direction once they arrived. Mark Noll, who has been my teacher and mentor for thirty years, and Philip Benedict, whose social history of Calvinism set the standard for Reformed Protestant studies, gave very helpful sets of comments that improved the book significantly. Colleagues at Hillsdale College, Richard Gamble, Matthew Gaetano, Paul Moreno, and David Stewart, reacted to ideas in conversations and informal presentations that let me know whether I was going in the right direction. Former colleagues at Westminster Seminary California, W. Robert Godfrey, David VanDrunen, Ryan Glomsrud, John Fesko, Bryan Estelle, Joel Kim, Michael Horton, and Charles Telfer, raised good questions during presentations at the school's Warfield Seminar. Ryan Glomsrud deserves special mention for being an important sounding board while he and I attended the 2009 Calvin conference in Geneva, and for giving useful guidance on Karl Barth.

From the time that I first submitted a proposal to the day when I finished revisions I experienced a number of personal challenges that go with the territory of human existence. My wife, Ann, and good friend, John Muether, were a limitless source of encouragement during these trials. But deserving special thanks are Jim and Nancy Loux, to whom I dedicate this book. In countless ways their friendship softened life's blows and lifted my spirits so that writing this book never became a burden but remained a pleasure.

Hillsdale, Michigan

September 17, 2012

Introduction

F OR CLOSE TO FIVE centuries, Geneva, the city that gave birth to Calvinism, has enjoyed an international influence. John Bale, a refugee to Geneva during the Reformation and a friend of the Scottish reformer, John Knox, marveled at the city's polyglot demographics. To see Spaniards, French, Scots, English, and Germans disagreeing in speech, manners, and apparel, sheep and wolves, bulls and bears, being coupled with the only yoke of Christ, was a wonderful miracle of the whole world. Three centuries later, in 1863, Henry Dunant, a native of Geneva and disciple of the nineteenth-century revival of Calvinism in his home town, led the group of Genevan humanitarians responsible for launching the International Committee of the Red Cross. This organization solidified Geneva's reputation as home to international relief efforts that would inspire the League of Nations and the United Nations High Commission on Refugees. The close identification between the city and international humanitarianism lives on in the commonly and widely invoked Geneva Conventions.

Humanitarianism is not the first thought that comes to mind with Calvinism. John Calvin is best known for thundering against human depravity and promoting divine sovereignty such that only a predestined few escape eternal damnation. This constellation of beliefs prompted the American journalist, H. L. Mencken, to place Calvinism in his cabinet of horrors, right next to cannibalism.

But Mencken's was a minority perspective on Calvinism during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Scholars like Max Weber and Robert K. Merton were busy attributing to Calvinism the genius of modern civilization from capitalism and democracy to natural science and freedom of inquiry. This was a different and more productive side of international Calvinism than Dunant's Red Cross. Instead of drawing the world's displaced and persecuted either to Geneva or to the local offices of the Swiss city's international organizations, the Calvinism praised by scholars and statesmen between 1860 and 1930 was a religion that migrated out from Geneva to change the world. Either way, Calvinism was a faith with international stature. Of course, other varieties of Christianity also possessed extensive networks of churches and agencies around the world. But none of them were as identified as Calvinism was with Geneva and its message of a better world.

Next page