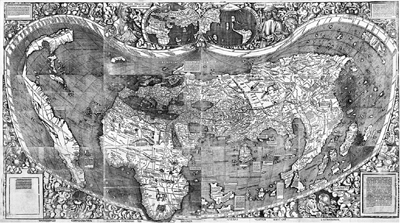

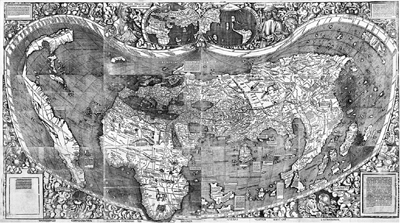

Map of the World, 1507, by Martin Waldseemller

Image: Held by the Library of Congress. The only surviving copy of the 1507 world map by Martin Waldseemller, purchased by the Library of Congress and now on display in its Thomas Jefferson Building in Washington, D.C.

Acknowledgments

A project of this kind cannot go far without supporting friends and backers. The investigation began in Edinburgh in the summer of 2006 with a grant from the then Kaleo Center of Covenant College, directed by Dr. Kevin Eames. More recently Covenant College has assisted with a six-month sabbatical, January-June 2009. I have been assisted at every step of the way by Covenant College librarians John Holberg and Tom Horner, who were unstinting in securing Inter-Library Loan materials. A variety of friends (some gained purely through the advance of this project) assisted me by reading and commenting on various chapters. Among these are Lyle Bierma, David Calhoun, Reid Ferguson, Cameron Fraser, Michael Haykin, Ed Kellogg, Travis Myers, A. J. deVisser, Herb Ward, Jack Whytock and Jason Zuidema.

Two chapters of this work have already appeared elsewhere. Chapter four appeared in an earlier draft as The Points of Calvinism: Retrospect and Prospect, Scottish Bulletin of Evangelical Theology 26, no. 2 (2008): 187-203, while chapter five appeared in an earlier draft as Calvinism and Missions: The Contested Relationship Revisited, Themelios 34, no. 1 (2009): 63-78.

Here I also record my gratitude to my oldest son, Andrew, a rising graphic designer. He closely consulted with me in gathering and editing the images that introduce each of the chapters in this book.

Antique Justiceor Theocracy?

Image: Clipart.com

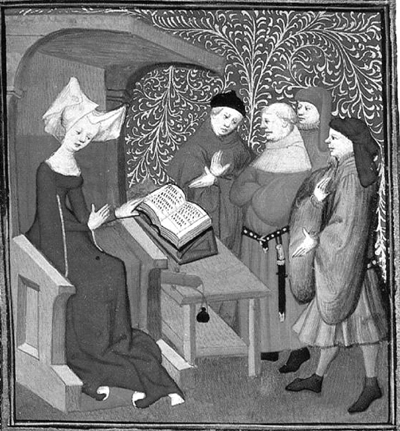

Christine de Pizan (1363-1434) Lecturing

Image: Wikipedia

Dutch Calvinist Iconoclasm, 1566 from an engraving by Franz Hogenberg in Michael Aitsingers De Leone Belgico (Cologne, 1588)

Image: Wikipedia

George Whitefield, The Awakener

Image: http://faculty.polytechnic.org/gfeldmeth/lec.ga.html

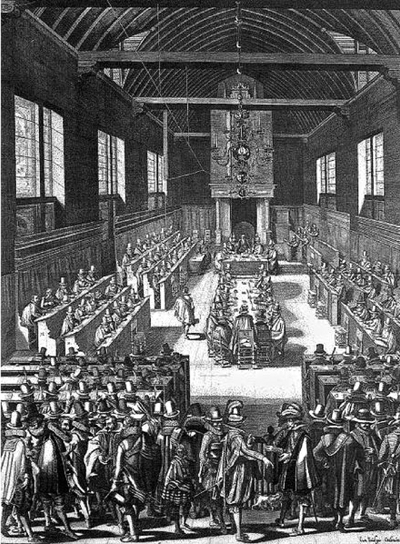

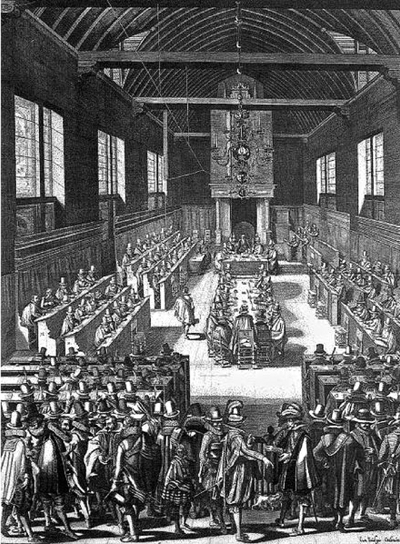

The International Synod of Dordt, 1618-1619 by Bernard Picart, 1729

Image: Wikipedia

Introduction

Why Pinpoint Ten Myths?

This book is written with Calvinists in mind, yet I hope it will also prove useful both to those who hold no opposite theological position as well as those who have consciously decided that the Calvinist position is not for them.

I have now adhered to what can be called the Calvinist theological position for almost forty years, after being raised and converted to Christ in an evangelical setting in which neither this Yet by my early adulthood I had come to see this attempt at doctrinal balance (as it was indeed called) as a minus rather than a plus. My pietistic evangelical background had leaned toward what could be called revivalism; in this setting many a zealous evangelist had succeeded in convincing me that I, a struggling adolescent Christian, was no real believer at all and that the only thing to do was to begin with Christ (yet) again. In hindsight this utterly unstable way of living as a Christian seems very much like the childrens table game Chutes and Ladders: one wrong move and I find myself starting over at the beginning! The question of Gods fixed opinion of me, or whether God had any interest in preserving me in a state of salvation once I was there, was for me a deep question with no certain answer. Certainty was very elusive in this pietistic and revivalist stream of evangelicalism.

Some Christians known to me held what were called Calvinist views, and these individuals seemed to possess a kind of swagger and certainty about such questions; I found this to be simultaneously unnerving and attractive. There were many late-night debates and certain recommended authors, but I was not won over easily. Embracing this understanding of Gods dealings with humans and the world took some time. Yet, incrementally, I came to embrace what is called Calvinism. This new loyalty also involved my taking what I now recognize to be some wrong turns. For I did not cease to be a pietistic evangelical; I became a pietistic evangelical with a Calvinist backbone. Paramount in my embrace of this new perspective was the consideration that Gods own initiative in my salvation had preceded my reception of it. His antecedent intention had undergirded and enabled my response; I had nothing that I had not received (1 Cor 4:7); if I was in Christ it was because of him (1 Cor 1:30). God has long-term commitments.

So, why have I, who have embraced Calvinism, written a book like this for those who are already consciously Calvinist? I can think of five reasons:

1. Like some other strands of Christianity, the Calvinist strain has a tendency to generate its share of extremists. Call them high-flyers or ultras if you like, but Calvinism has generated its share. I am not referring here to people who are rude or crude (though there are in fact Calvinists of this type too) but more particularly to those who know no limits; to use an aeronautical metaphor, they fly without an altimeter. Certain aspects of Calvinism are their hobbyhorses; all discussions will eventually return to their pet Calvinist doctrines. It troubles me that the Calvinist movement seems to be reluctant to admit that this tendency to extremes exists; no one seems to blow a whistle on those who are out on the rim of things. I suppose that the expectation is that since Calvinism is good, it is impossible to have too much of a good thing. I myself was positioned on this rim for a period.

The tendency to extremism is not unique to Calvinism; Methodism in its Holiness tendency became known for those

Yet it seems to me that Calvinism has had more trouble restraining its ultras than some other forms of Christianity. Perhaps Calvinisms reluctance to do this reflects the prominence given by the movement to the conception of God as omnipotent (a belief which I do not dispute). Calvinists are united in a strong conviction of Gods sovereign power; they expect to see this divine sovereignty exercised in the ultimate triumph of the gospel and of certain theological principles; why then think about boundaries or limits? But this obsession with omnipotence is lopsided; it is not sufficiently recognized today that because of it Calvinism is quite capable of assuming degenerate forms.

The biographer of a much-admired Scottish minister John Erskine (1721-1803) insisted The French have a proverb that goes plus a change, plus cest la mme (the more things change, the more they remain the same). Because tendencies to the extreme recur, I am writing in the hope of encouraging Calvinists to stay in their movements mainstream and to learn to say no more confidently to upstarts who claim, alone, to have the inside track on the Calvinist tradition.

Next page