InterVarsity Press

P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515-1426

ivpress.com

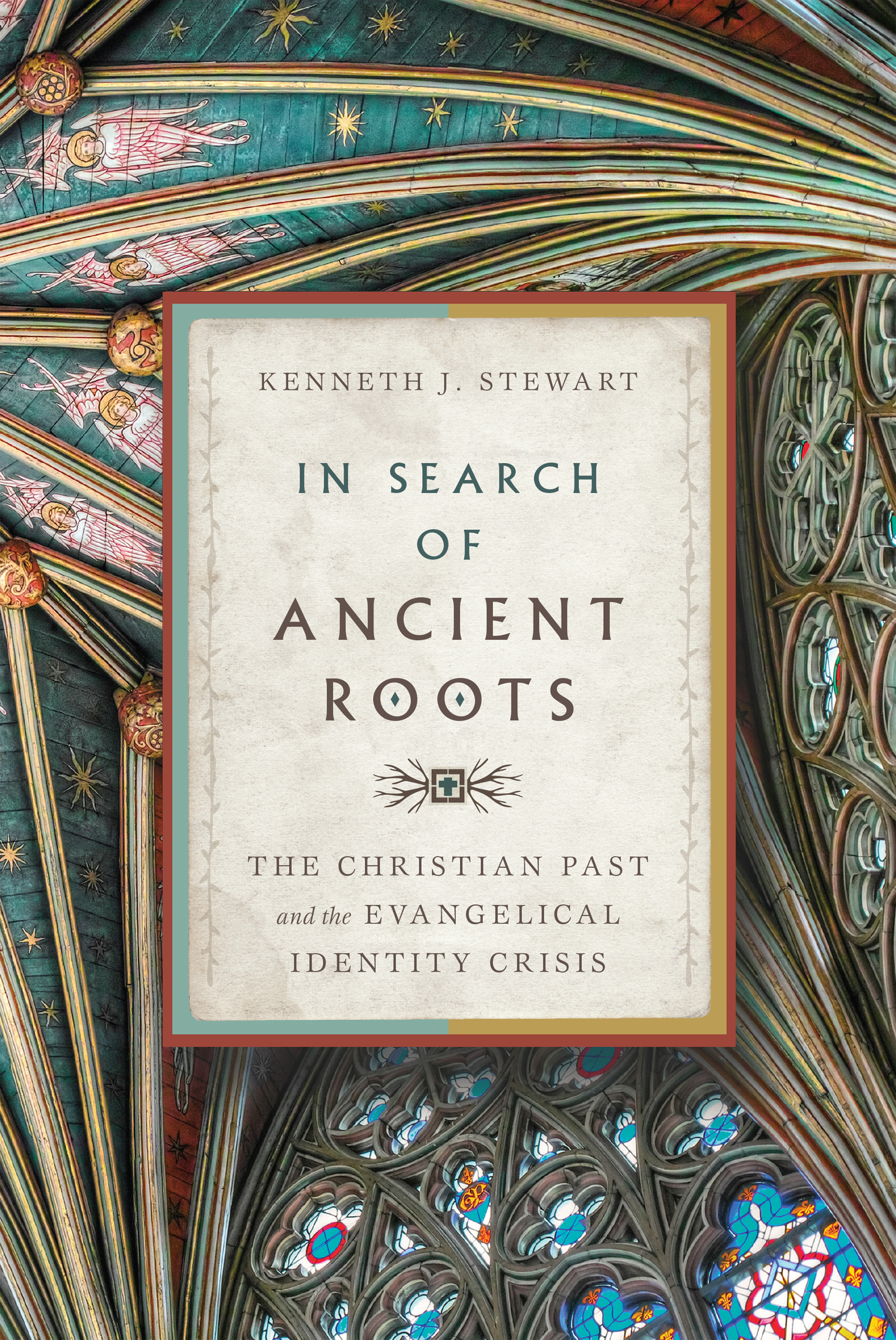

2017 by Kenneth J. Stewart

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

InterVarsity Pressis the book-publishing division of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA, a movement of students and faculty active on campus at hundreds of universities, colleges, and schools of nursing in the United States of America, and a member movement of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. For information about local and regional activities, visit intervarsity.org.

All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from The Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com The NIV and New International Version are trademarks registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by Biblica, Inc.

While any stories in this book are true, some names and identifying information may have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

Appendix A, The Colloquy of Regensburg (1541) on Justification is reprinted with permission from A. N. S. Lane, Justification by Faith in Catholic-Protestant Dialogue: An Evangelical Assessment (London: T&T Clark, 2006).

Cover design: David Fassett

Images: Quentin Bargate / Getty Images

ISBN 978-0-8308-9260-0 (digital)

ISBN 978-0-8308-5172-0 (print)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stewart, Kenneth J., author.

Title: In search of ancient roots : the Christian past and the Evangelical

identity crisis / Kenneth J. Stewart.

Description: Downers Grove : InterVarsity Press, 2017. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017038108 (print) | LCCN 2017033994 (ebook) | ISBN

9780830892600 (eBook) | ISBN 9780830851720 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: EvangelicalismHistory. | Church history.

Classification: LCC BR1640 (print) | LCC BR1640 .S687 2017 (ebook) | DDC

270.8/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017038108

TO THE MANY FRIENDS AT

L OOKOUT M OUNTAIN P RESBYTERIAN C HURCH ,

L OOKOUT M OUNTAIN , T ENNESSEE ,

who by their shared concern for this subject and

by personal encouragement have helped

move this book toward completion.

Acknowledgments

This subject has been on my mind for more than a decade. Such is the profusion of literature bearing on the subject of how and why we ought to appropriate from ancient Christianity that I have often described my situation to friends as that of a man chasing a moving train that has already left the station. At some point, one simply has to be content with what one has read and stop reading.

Across this decade or more, various parts of this book have first seen light as essays and conference papers. Chapter five was delivered in the 2007 Wheaton Theology Conference and then appeared in the Evangelical Quarterly (80, no. 4 [2008]: 307-21). Chapter seven first saw light as a contribution to a festschrift edited by Ian Clary and Steve Weaver, The Pure Flame ofDevotion: The History of Christian Spirituality; Essays in Honor of Michael A. G.Haykin on His Sixtieth Birthday (Joshua Press, 2013). Chapters ten and eleven began as short essays in Books and Culture (MayJune 2003 and MarchApril 2011) and have been expanded here. Chapter twelve appeared in Themelios (39, no. 2 [2014]: 268-80). The Evangelical Theological Society has provided a venue for the presentation of drafts of six chapters (6, 7, 8, 12, 13, and 15). Thank you, various auditors, for help along the way!

Various friends have commented on parts of this project. Among these are Leonardo De Chirico, Cameron Fraser, Ernie Manges, Michael Svigel, and Jack Whytock. I am indebted to the two Covenant College student assistants who assisted me at various stages: Sarah Grace Kaye and A. J. Millsaps.

I especially want to acknowledge the kindness of my wife, Jane, who has proved to be my indefatigable and thorough editor.

INTRODUCTION

The Situation from Which We Begin

Evangelical Christianitys Current Self-Doubt

Evangelical Christianity is now a surging global phenomenon. Such writers as Philip Jenkins, David Martin, and David Aikman have reported that Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asias Christian future looks increasingly evangelical in the sense of embracing Biblicist, Christ- and cross-centered, conversionist, and Holy Spiritoriented Christianity. But in western Europe and North America (the regions from which pietistic and evangelical expressions of Protestant Christianity were transmitted to the global church), the current era is one of increasing introspection and self-doubt.

This introspection and self-doubt has not to do with any sheer loss of momentum, for church planting goes on apace in western Europe and in North America, and the evangelical knack for adaptation to emerging circumstances and cultural change is still alive and well. No, the introspection and self-doubt are the result of three principles still being worked out.

Three Principles

The run-down factor . These are, first, the increasing distance of space and time from the period of evangelical origin and a resulting run-down. Original ideals and guiding principles can lose their edge over time. I hold that todays evangelical movements are the linear descendants of the popular late-medieval religious movements that eventually gave rise to the various Protestant movements of the sixteenth century (Anabaptist, Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican). Many of the early Protestants had first been agitators for spiritual religion in the years before Luthers protest of 1517. These initially regional movements (not all of which entered Protestantism at its emergence) were both diffused over wider regions than those they initially affected and in turn were modified through adaptation to new cultures and contexts. In the early modern period, evangelical Christianity went global. But this gradual and natural adaptation, when combined with a gradual loss of momentum, also provoked second thoughts about the need to recover earlier evangelical ideals.

Thus, by the closing decades of the seventeenth century, Dutch and German Pietists as well as the Puritan inhabitants of New England were noting and lamenting the running down of evangelical religion and praying for its recovery; this in fact occurred in waves beginning in the 1680s and 1690s on both sides of the Atlantic. The better-known period of the eighteenth century, which we have come to call the Great Awakening or Evangelical Revival, extended this recovery of momentum until the dawn of the next century.

The nineteenth century, especially, witnessed Protestant attempts to recover afresh the original purity of apostolic Christianity. The emulation of the Christianity of the Acts of the Apostles became all the rage circa 1830; whatever had happened