FORTRESS 14

FORTIFICATIONS IN WESSEX c. 8001066

| RYAN LAVELLE | ILLUSTRATED BY DONATO SPEDALIERE |

| Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic |

Contents

Introduction

In an entry for the year 789, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded the first of what was to be a series of attacks on the kingdom of Wessex. A royal reeve, entrusted with ensuring the collection of tolls and taxes from traders, went down to the coast at Portland, Dorset, where three ships had drawn ashore and attempted to summon their crews to the kings manor. The visitors, from Hrthaland in Norway, were distinctly uncooperative and the reeve was promptly killed.

It was an inauspicious start for a terrifying movement that was to sweep across Western Europe in the following century, but it was perhaps fitting that this early attack should have been so implicitly concerned with trade. Attacks upon monasteries and churches, such as the better-known assault upon the monastery of Lindisfarne in 793, attracted the attention of the literate churchmen who dominated the recording of history. However, it was to be the economic as much as the religious impact of the Viking raids, which meant that the rulers of western Europe had to consider how they could best defend their realms against an increasingly dangerous external threat.

Wide-scale archaeological excavations of urban sites have shown that during the 8th century large international trading sites had been placed under a high degree of royal control, with close attention paid to their layouts. Examples such as Hamwic (Southampton) and Gippeswic (Ipswich) in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and Quentovic and Dorestadt in the Frankish realms (now France and the Netherlands), show that kings had vested interests in controlling and promoting trade within their realms. Coins were minted in such places and royal manors were close by. The problem was that the only real protection for these sites was a recognition of the authority of the king as a giver of peace; beyond small ditches marking out the sites, there were no physical defences to speak of. These sites were obviously vulnerable to an increasingly dangerous threat.

By the early-9th century, Anglo-Saxon England consisted of four main kingdoms: East Anglia, Wessex, Northumbria and Mercia. Of these, Mercia was then the most powerful, militarily and economically, but in the later-9th century it was the kingdom of Wessex that was able to survive the attacks of the Great Army (Micel Here), a motley collection of Scandinavian raiders who had all but destroyed the other three kingdoms during a decade of fighting.

To meet this problem, there was a gradual movement in the 9th century from undefended wic trading sites to trade taking place in defended sites, known in Old English as burhs. Urban fortifications such as those used in the burghal system were not a West Saxon innovation within either Anglo-Saxon England or Early Medieval Europe, but their systematic consolidation and regulation, probably under the system of administering fortifications recorded in the document known as the Burghal Hidage, may reflect the fact that it was Wessex, and the later kingdom of England under the West Saxon kings, which ensured that the defended urban site became an essential part of their success. Some 30 well-structured fortifications formed a framework of defence across the West Saxon heart of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom from the late-9th century onwards, a development that consolidated Alfred the Greats earlier victories.

However, some points of definition should be addressed at this stage. Although the work of many scholars would seem to suggest that it had assumed such a definition, the term burh did not mean a fortified town per se. Anglo-Saxons used the word to denote any place within a boundary, which could include private fortifications or simply a place with a hedge or fence around it. Indeed, the term hage simply meant boundary, so a hedge may have been a fence rather than a line of trees and bushes, even if the distinction between the two may have been blurred by the fact that fences could resemble hedgerows if they were not attended to regularly. As one historian has pointed out, this term could even include the miserable existence of the kinless woman in the Anglo-Saxon poem The Wifes Lament, whose burh consisted simply of the brambles around the cave where she dwelt. Many burhs could also be privately occupied fortifications in effect, early castles. Nevertheless, the organisation, administration and defence of the system of communal fortifications designed as sites for a number of people in later Anglo-Saxon England, many of which became towns, are the main focus of this book.

Strictly speaking, Anglo-Saxon Wessex refers to the historic shires (later counties) of Devon, Somerset, Wiltshire, Hampshire and Berkshire, which formed what has become known as the heartland of the West Saxon kingdom. However, not least because of the dominance of the West Saxons over the areas of Sussex, Kent and Cornwall, the West Saxon kingdom gained hegemony over lowland Britain even before the Vikings became a major threat. Therefore, a consideration of Wessex here is a flexible one and reference will be made to those areas of Mercia south of the Danelaw boundary that fell into West Saxon hands as a result of victories against the Vikings in the late-9th and early-10th centuries.

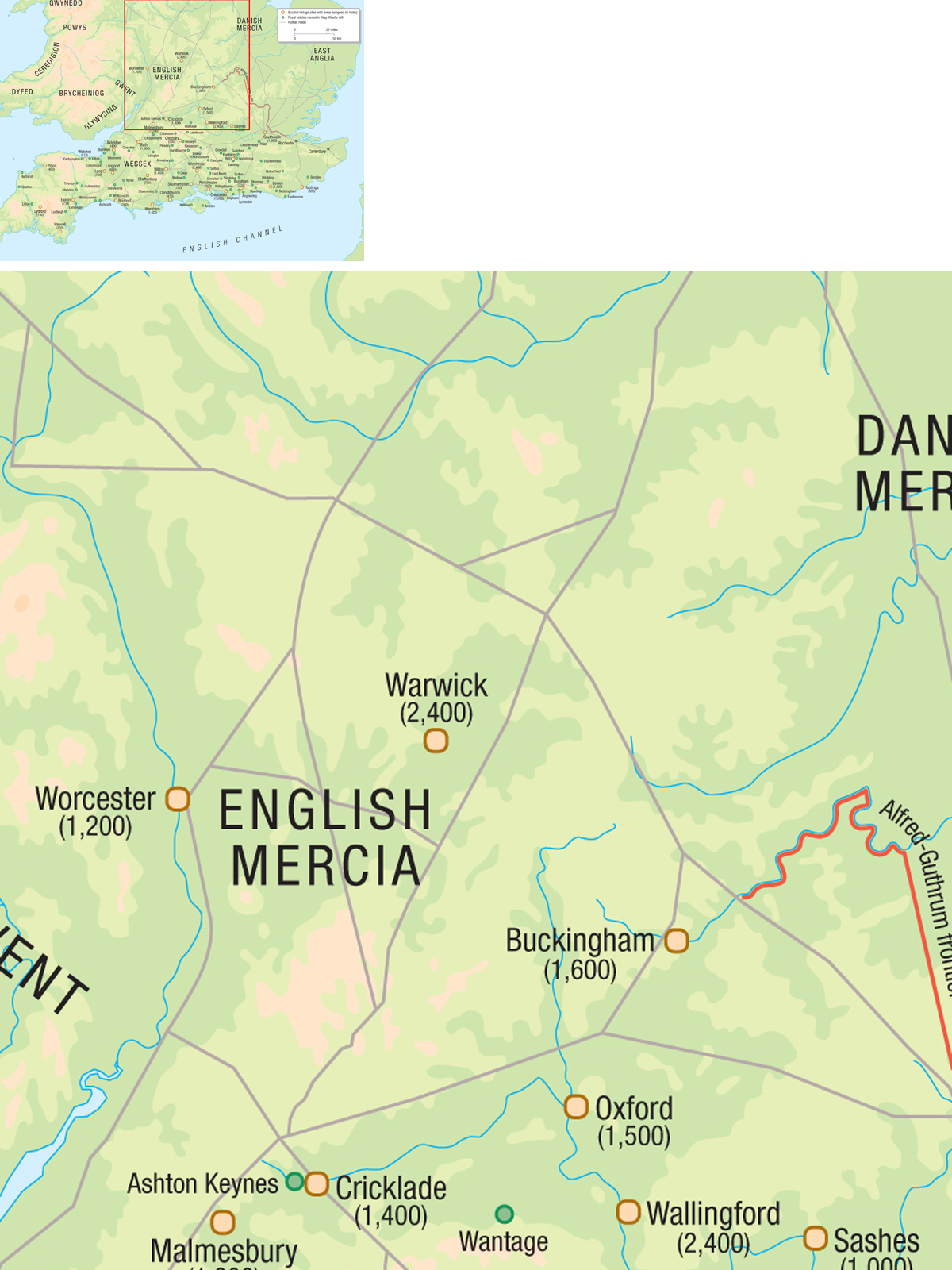

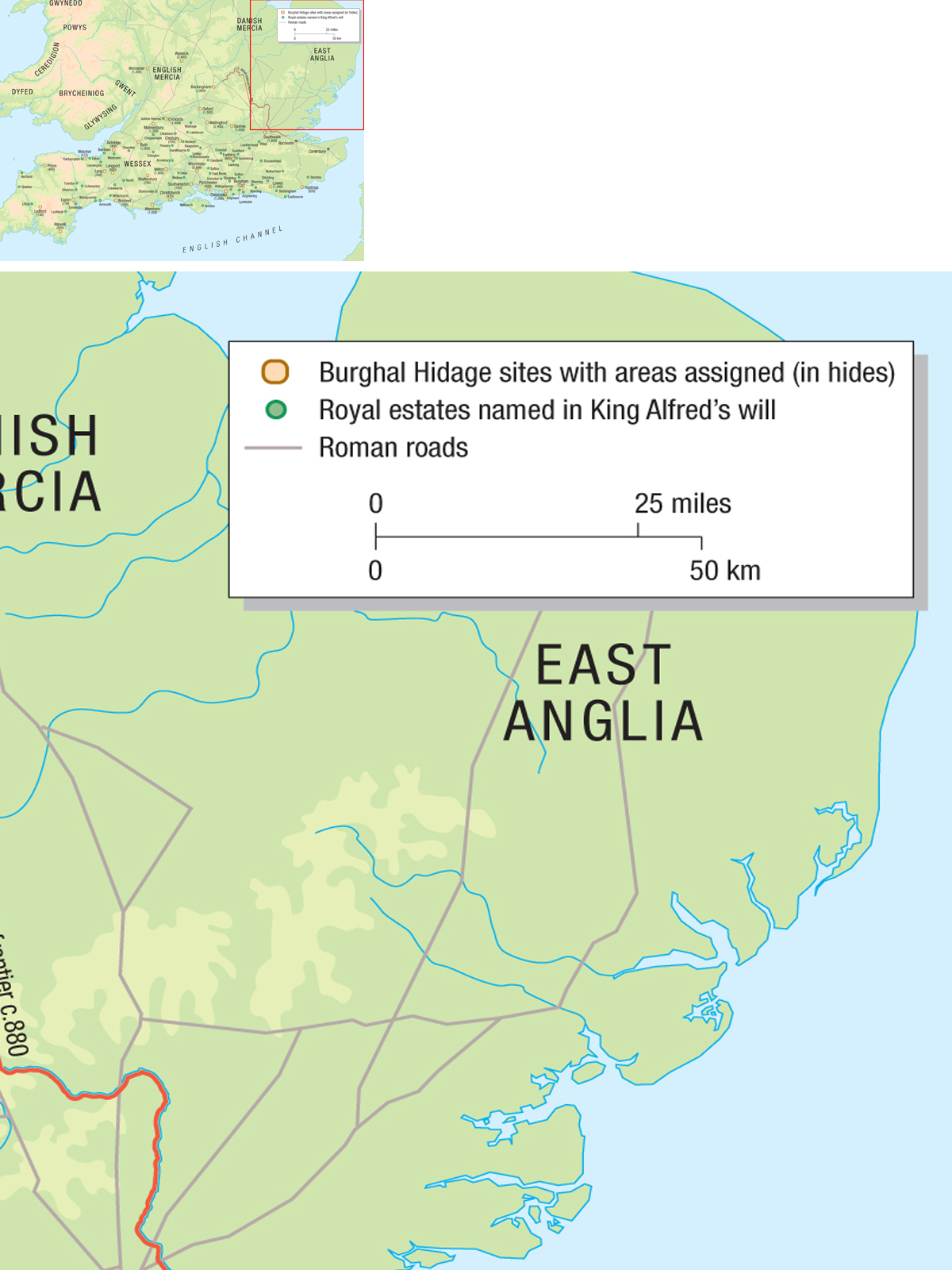

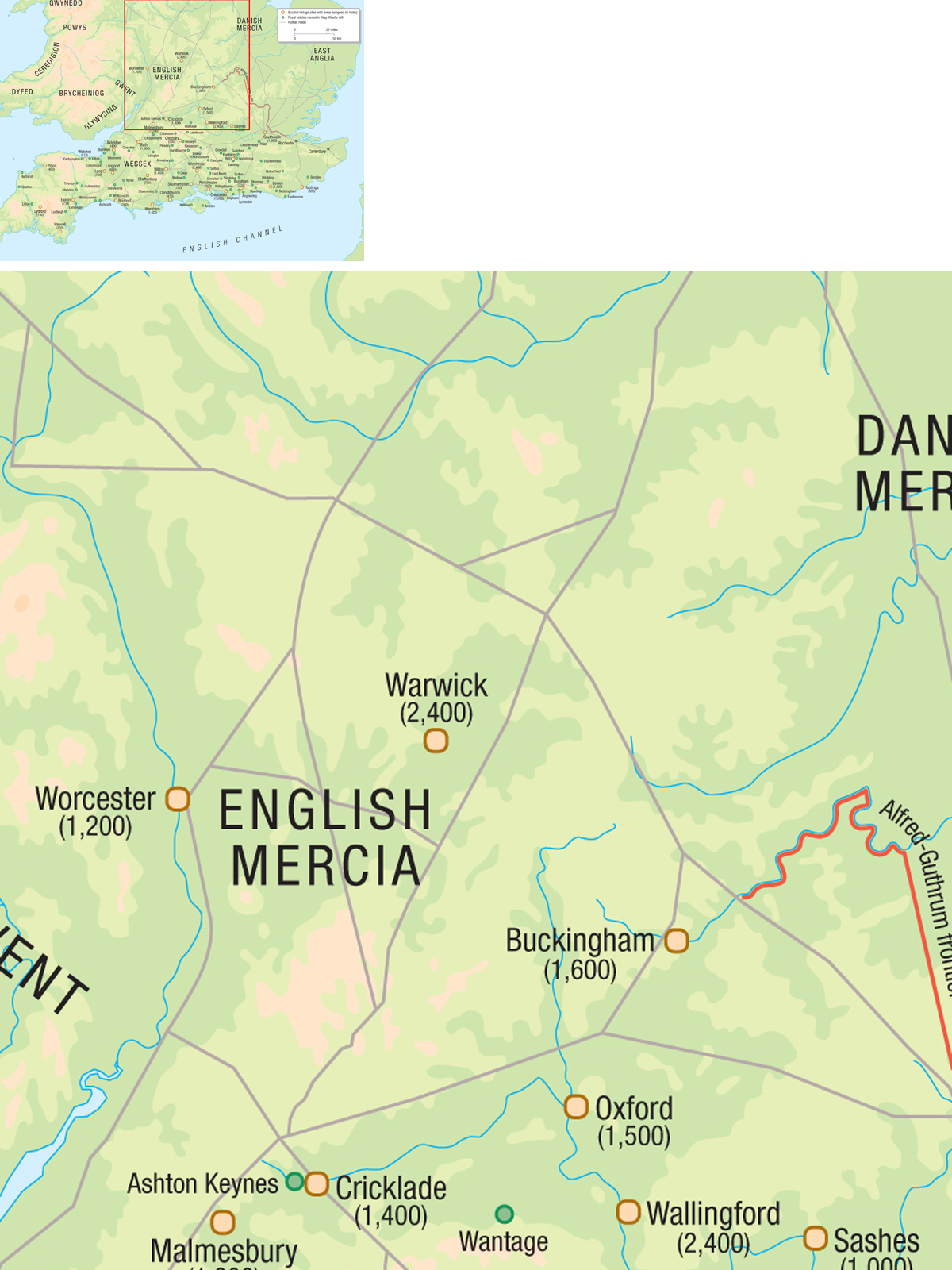

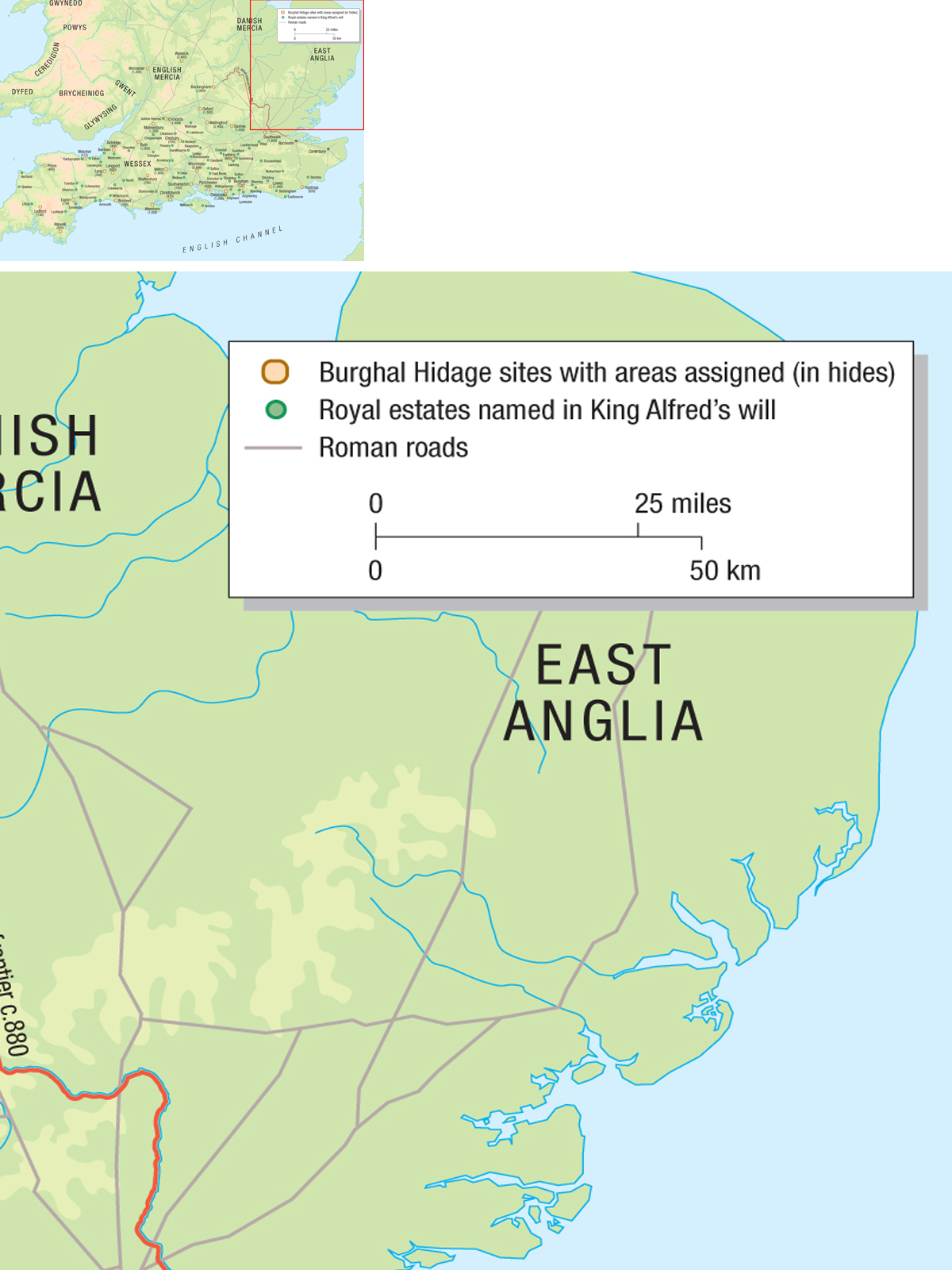

The kingdom of Wessex and its neighbours. The map shows the 32 places which can be identified with varying levels of certainty in the Burghal Hidage, a document that dates from around 916 and records the amounts of land necessary for the maintenance of particular fortifications. Amongst various theories explored regarding the origins, purpose and nature of this document, it has been suggested that this may have been a paper exercise, designed to work out what would be needed for the maintenance of the West Saxon network of fortifications. The map also shows the relationship between the private resources of the West Saxon royal family, as shown in the will of King Alfred the Great, the communication network of Roman roads and trackways, and the 9th-century fortifications. Although there were other estates under royal control besides these shown in Alfreds will, the map still shows the importance of controlling the landscape, as envisaged by King Alfred.

Chronology

| c. 749 | First record of rights of burh-work made in an Anglo-Saxon (Mercian) charter |

|

Next page