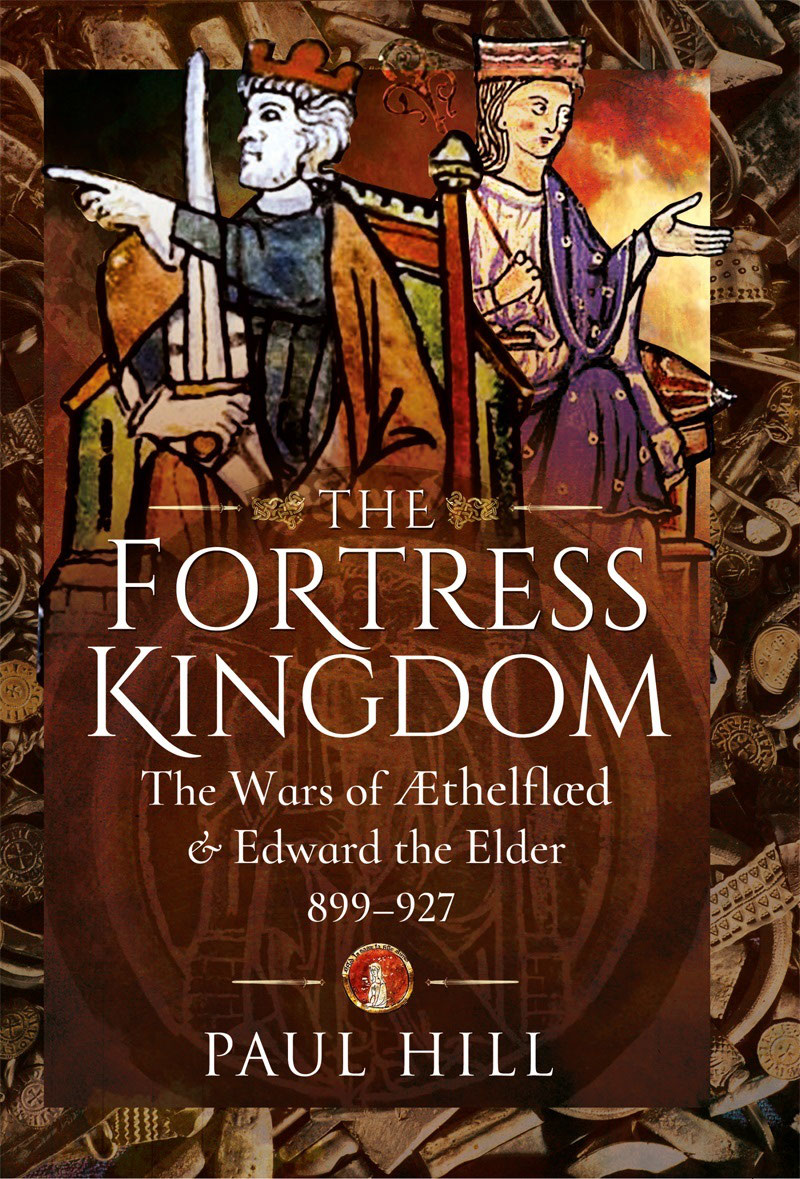

The Fortress Kingdom

The Fortress Kingdom

The Wars of thelfld and

Edward the Elder, 899927

Paul Hill

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Paul Hill, 2022

ISBN 978 1 39901 061 0

ePUB ISBN 978 1 39901 062 7

Mobi ISBN 978 1 39901 062 7

The right of Paul Hill to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and White Owl

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LTD

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail: Uspen-and-sword@casematepublishers.com

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Contents

Photograph Credits

Colour Plates

Black and White Photographs

List of Maps and Plans

A Note on the Charters

The charters referred to in this book are noted as S numbers. These relate to P.H. Sawyers 1968 publication Anglo-Saxon Charters, an Annotated List and Bibliography. London. An electronic version is to be found at https://esawyer.lib.cam.ac.uk/about/index.html [accessed 01/12/2020].

Acknowledgements

The making of this book has involved a good deal of travel to many places across England, something which had become much harder than usual during the period in which the book was written. I am very grateful to the staff of several public and private museums and visitor attractions for their kind help, both in person and of course remotely. It has not always been easy to get to places due to recent developments, but wherever I have gone I have been welcomed. Church staff in Bedford and in Tamworth have given me much-appreciated guidance. In particular, to Rachel Pardoe of the Gloucester City Museums Service and her team who organized the photography of the tenth-century grave slab in their collections, I am most grateful. To the staff of Hertford Museum I am grateful too, for their guidance regarding the towns development. At Leicester as well, particularly at the Guildhall, where the delightful replica of the statuette of Ethelfloeda now stands proudly in the courtyard, my thanks for allowing me to spend so long with it. Chester Tourist Information Centre, and everywhere I went in Chester, were all welcoming. I am grateful to the Cathedral and staff for their assistance. Similarly, the staff at Worcester Cathedral have also been most helpful. Thanks also to the staff of the British Library Reading Rooms at St Pancras, where much research has been carried out. They too have had to respond to the pressures of maintaining a public service in the middle of a pandemic. I must also however, thank my wife Lucy, for her forbearance in enduring what has been a very long-lasting passion and in tolerating my sudden disappearances.

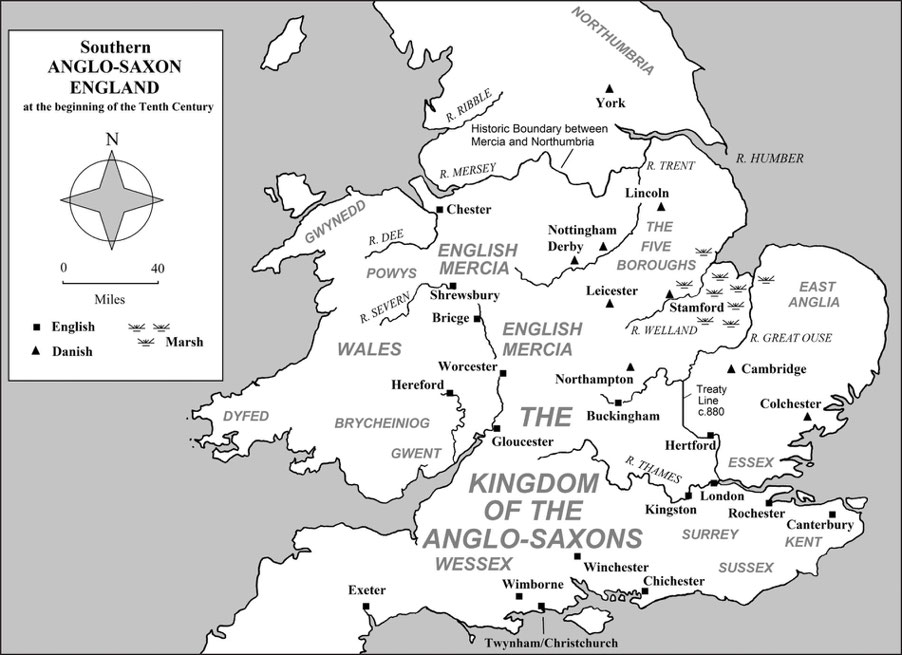

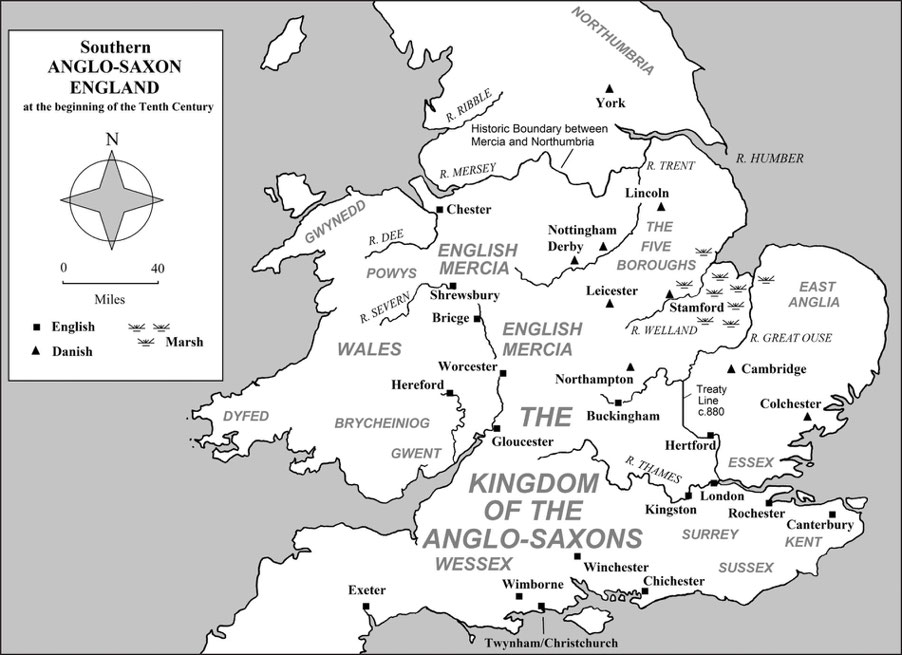

Map 1: Southern Anglo-Saxon England at the beginning of the tenth century.

Introduction

This book is the second in a series of volumes about the formation of England. The series focusses on the achievements of the family of Alfred the Great (87199) and their descendants, concentrating on their wars and their lives. Throughout this era, the way in which rulers used their faith as a tool to bring legitimacy to their rulership also played a big part in their lives. In some cases, it was as if the Christian faith itself was defining the ruling classes against the backdrop of pagan practices and Scandinavian settlement. But this was a cosmopolitan world not just in terms of religious practices, but equally importantly of opposing lordships and desperate political and military struggles. The achievements of the children of Alfred is not the only story to be told here. The first book in the series, The Kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons the Wars of King Alfred 865 899, recalled the rise of the West Saxon kingdom during an era of great turmoil. The first Danes had caused destruction around the shores of the country, falling upon the Holy Island of Lindisfarne in northern England in 793 and firmly planting themselves off the shores of Ireland. These early incursions had left the English kingdoms ruling elites only partially affected, until the arrival in 865 of the Great Heathen Army under Ivar, Halfdan and Ubba, the semi-legendary sons of the enigmatic Scandinavian Ragnar Lothbrok.

Although many Danes began to over-winter in England off the coast of Kent from around the 850s (and in Northumbria, probably even earlier), it was the sheer size combined with the resolute intent of the Great Heathen Army which set them apart from so many of their Scandinavian predecessors. The sagas speak of a vengeance mission against the Northumbrian King lle (c. 862/67 or c. 867), who had allegedly killed Ragnar by having him put in a pit of snakes, in what was one of the more alarming of his many notable deaths. They may or may not be right. But what is undeniable, is the effect the Great Heathen Army had on England. Northumbria fell to the army in 867 and the Danes installed a local ruler before heading south. The East Anglian King Edmund (85569) was martyred at their hands in 869 and became not only a saint, but was even commemorated on coinage issued by none other than the later Scandinavian rulers of East Anglia itself.

Mercia, the central Midland English kingdom whose power was unmatched by any other kingdom during the reign of the mighty King Offa (75796) had experienced a turbulent relationship with its southern neighbour Wessex up until the arrival of the first Danes. A decline in Mercian power and fortune began in the early ninth century amid dynastic strife and the rise of the West Saxon house of Ecgberht, the grandfather of Alfred the Great. At his height Ecgberht was heralded by the writers of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as the last of the great Bretwaldas of old, a ruler over other kings. He had even at one stage taken London from Mercia and also marched his forces up to the traditional border of Mercia and Northumbria. But Mercia somehow held on, with its warring families vying for the throne in turn. Many of these families seemingly belonged to lineages identifiable by the alliteration of their names. The C dynasty, with its allies from the W dynasty, at times were set against the B dynasty, for example. But these families had pedigrees: some could trace themselves back to ancestors near to the dawn of Mercian kingship, or at least could make a good argument for it. When you could do that, it was all to play for in Anglo-Saxon England. And so from the reign of Coenwulf I (796821), through the struggles of King Beornwulf (8236) and his supporters against the East Angles, to the rise of King Wiglaf (8279 and 8309) and the reign of Beorhtwulf (84052), the Mercian story had been one of familiar intrigue played out on a stage overshadowed by the prowling Dane and the gradual rise of the house of Wessex.