Table of Contents

Guide

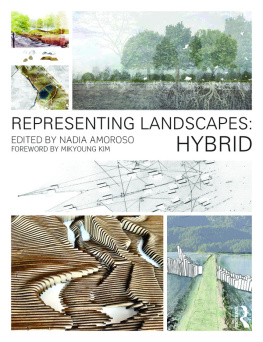

Once the world was wide. Now we live in collapsed space: the chip in our pocket. Once wilderness was beyond society. Now even the storm bears our imprint. We are awed by ourselves. We are frightened by ourselves. We have acquired godlike powers. We cant govern ourselves. Besotted by our grandeur, we consider geo-engineering. Befogged by our data we grope for transcendence. We pretend we are small, a figure in the furrowed field, sowing, woodlots and windrows riding the hills to their crests all around us, as always. But wherever we turn we bump into ourselves. We live as in a walled garden now, walled by ourselves. We have been building this wall for some time, but now its complete. That is new. And yet our surroundings remain as radiantly mysterious as ever. The connection to place remains deep: touching the core of our being. Landscape is our mirror, our book of revelations, as always. This is where reorientation starts.

T he windows of the mill are dark. But I have seen the works inside: the two pairs of millstones, fluted for gristing, the sifters, the shuckers, the hoppers, the conveyers, the belts and the pulleys and the cast-iron turbine. Thinking of them I become aware of the millworks of thought and feeling in me. The gristmill is just across the road from my cottage. Its a big wooden structure, three stories, painted an old red, reaching down the bank to the stream. Just by the mill is a dam. From inside my cottage I hear the steady sound of the falls going over the dam. The mill was built in 1880, replacing another that burned. Its geometry is time-softened, but it still carries itself with an air of prosperity and confidence.

A little ways upstream, in the woods, a long, stepped, natural falls comes over a ledge high above and down through a gorge. At the bottom of the falls the stone foundations of another mill, half collapsed and mossy, are disappearing in the woods, rooms half filled with drifts of fallen leaves. Compared to the gristmill, these ruins convey a cramped, hard-wrested quality. But this was a big woolen mill, also three stories, where felt was produced. Felt made from sheeps wool was used in the production of paper, and became the great industry of the village. The gnarly little mountains around here are good for sheep. When the woolen mill was in operation, a flume siphoned water from the top of the falls down to the mill at the bottom, a descent of a hundred feet, into the mill, into the turbine, inside of which was a small wheel of vanes turned by the concentrated water, powering the works. Once, even the pitching land around the gorge was pasture. Now all the slopes that enclose the village are wooded.

From the gristmill the village tumbles downhill, above a small widening floodplain, alongside the tumbling stream. A reproduction of a print that I bought at the Historical Society, which now occupies the gristmill, is taped to the wall above the bathtub in my cottage. It shows the floodplain in the nineteenth century, busy with industry: largely lumberingbig tree trunks, some strewn about, some stacked. You can tell it was noisy and dirty. The work of agrarian times was not always as peaceful as we like to imagine. Indeed, there were once five mills along the stream. Today people get upset if a tiny business opens in the village, as if that would ruin its historical character. Midway down Main Street are town-house-style attached dwellings that were once lived in by merchants who ran shops at street level. Some houses along the way are substantial. The village is small, and yet there was substance here, reflecting a time when wealth and political power was in landthose pastures full of grazing sheep whose wool could be turned into felt. When wealth is in the land, then the countryside is less context, more the main thing. Its a spread-out scene, decentered, continuous yet with nodes, like a painting by Kandinsky. That land-wealth gave even a small settlement like the village importance. Other houses are farmhouse-sized with barns in back; others are tiny. Downstream, where Main Street gets steep, sundry houses and cottages are attached to one another to comical effect, as if to keep from falling. Beyond the last houses, the stream turns into a small valley of fields where it quiets.

The village is Rensselaerville, located in the Helderberg Mountains, a small range in the northwestern corner of the Hudson River Valley, between the Catskills and the Adirondacks in New York State. Its named for one of the Dutch patroon families that first settled the region. The arrangement was feudal, typical of the region. It held back more varied development until overturned by rebellious farmers. As a result, the earliest houses in the village are late eighteenth centurylate for the East. People here are place-proud, but in daily parlance Rensselaerville is just the village, and I will adopt that usage here because it captures a quality of anonymity, of solitude, of being the only villagenot quite on the map and perhaps a bit lost in time, too, that is the quality of many villages. Behind the anonymous solitude lies the history of a small productive society, an arrangement out of which the physical form of the village arose, including the specter of a previous feudal arrangement successfully routed. However stratified the architecture, there is a strong we in the close clustered physical village: a sense of something earned by all, and lastingpassed on: something modestly, collectively triumphant.

Landscape differs from region to region, but all our landscapes incorporate shifting layers of meaning, some purely personal, sometimes strangely close to the hidden springs of personhood, some familial where lines go back as they do here, intertwining, but always ultimately, to my mindeven when landscape invites us to solituderecalling our profound social connectedness, a sense of our lives together. Landscape to me is different from nature alone, from wilderness. It is the work of art that results from the collaboration between man and that which has been providedthe gift of providence, you could say, but whatever you say, it is not something man had a hand in at the start. Landscape is what arises from the hand of work as we make our living on the planet and our relation to one another as we do so. The hand of work creates in terrain a kind of syntax, an arrangement of interrelating parts, a composition that has a human meaning that is always, in part, beyond words. Landscape is different from wilderness: Wilderness only has meaning in relation to domesticated environments, while landscape is always part human, though never all human. All our physical surroundings, including the city, are landscapes. Architecture is a component of landscape, a maker of landscape, too. The mill is a landscape maker, literally connecting the parts. The village is a landscape maker, inseparable from its surroundings. The meaning of landscape changes from region to region but our landscapes are all, in one regard, related. The greatest power of landscape is that in expressing our collaboration with the physical worldwith that which has been providedand in that to each other, it becomes the armature of our common interior life; our most social dimension. This is the ultimate, most profound value of landscape.

Its raining today in the village. After a series of spectacular June days, in which the light was so bright and the shadows so dark one felt blinded, the rain is a relief. On June days of that sort, heaven seems to have come down and occupied the landscape, leaving us dazed and a bit embarrassed by our inadequacy. Without the wherewithal to take it in, we are stupid. When the sun begins to sink into the long evening we are reprieved. A rainy day is something different: just us. I like the lowered demands of a rainy day. Here in my cottage the sound of the rain is lost in the sound of the falls, but I can see its pattern against the side of the mill. The pattern is veil-like, a loose weave, but what has my attention are the spaces. The wind blows and the veil billows. The trees are blowing, too. I love a windy rain. What I see in the moving weave of spaces is the gorge, the floodplain, the valley beyond before the village was built. That transparency is always part of our American landscapes: still. The mill is old, and this draws me to it, but its age is thin. We Americans have a little to remember now, but part of what we remember is that not very long ago we had nothing to remember.

Next page