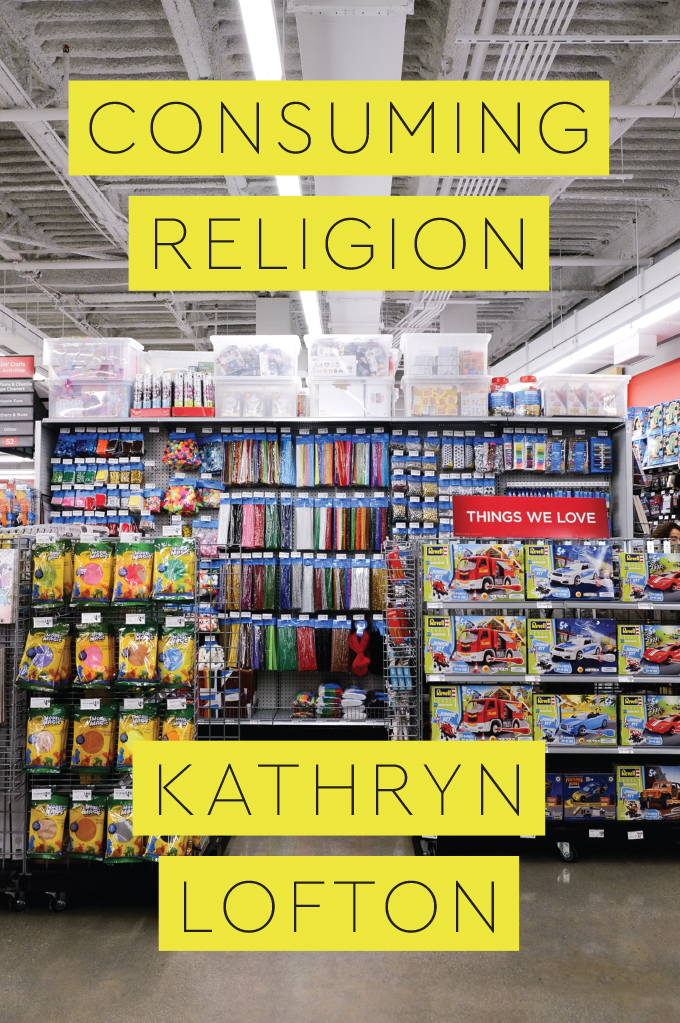

Consuming Religion

Kathryn Lofton

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2017 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 East 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-48193-7 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-48209-5 (paper)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-48212-5 (e-book)

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/9780226482125.001.0001

Published with the assistance of the Frederick W. Hilles Publication Fund of Yale University.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lofton, Kathryn, author.

Title: Consuming religion / Kathryn Lofton.

Other titles: Class 200, new studies in religion.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Series: Class 200: new studies in religion

Identifiers: LCCN 2016057343 | ISBN 9780226481937 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226482095 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226482125 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Religion and cultureUnited States. | Popular cultureUnited States. | Popular cultureReligious aspects. | Consumption (Economics)United States. | Consumption (Economics)Religious aspects.

Classification: LCC BL 65. C 8 L 64 2017 | DDC 306.60973dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016057343

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

For NKL

A society can neither create itself nor recreate itself without at the same time creating the ideal.

mile Durkheim

Contents

This is a book about how we organize our consumer life and how consumer practice organizes us. What am I free to consume? What do I become through consumption?

Consider a single page in an airline magazine. The two articles on the page will be familiar to any traveler who has been desperate enough to reach for seat-back literature. Familiar with the way the magazine deploys cartoon sketches and a perky vernacular to enjoin the reader to take other trips. And the articles are recognizable, too, in their strategic whimsy, how they want to ensure that nothing too serious enters your head when you are stuck at twenty thousand feet. Your mood is being managed, but what do you care? You are the one who grabbed for the airline magazine. Already youre a demographic, somebody targeted for certain credit card offers and pop-up ads.

The two articles on this exemplary page gush about their advertised destinations through the voices of two eager people named Avi Yossef and Scott Michaels. Even if you have not read this issue of the magazine, you can already imagine who they are. You know they will be entrepreneurs or adventurers; you know that they will be highly productive and keen to see new horizons; you know that they will be (as they will tell you) in love with life. These simulacra are like Saturday morning cartoon characters or the smell of coffee, nearly cozy in their familiarity. You return to them, reading this magazine even though you know nothing revelatory will be found on its pages. You read maybe because youre caught between one thing and the next, vulnerable to any distraction. Or maybe because you wonder if by the end of this reading something different might happen than happened so many times. I shop therefore I am, reads a 1987 work by the American artist Barbara Kruger.agential. High in the sky, waiting through the flight time, I am, therefore I consume.

The jetliner journalist quickly relates details of our businessmens ambitions. Scott is the director of a Los Angeles tour company, Dearly Departed Tours, through which paying guests explore what his company website calls the spectacular exits of Hollywood celebrities.

The articles are determinedly good-natured and foxily democratic. We are told that Avi has a trucker hat and Scott has a goatee. Reading these thumbnail sketches of their fixations, we are struck by how similar they are, these two lightly sporty men who have an odd tiger by the tail. Nobody has ever danced at the lowest point on Earth before, Avi says. Theres a historic story here.

Suddenly weve gotten to some specific words. Could this person really mean them? Reading a corporate periodical suggests we shouldnt press too hard on any of its particulars. Commercial products dont want to disturb their consumers with anything that upsets the shushing lull of their cloaked commerce. Stopping on those particular words raps against the compulsory concordance of the enterprise.

But what if you decided to resist the anti-seriousness of this text and ask whether it means precisely what it says? If movies are our religion, Graumans is a church, what does that mean? Bored on the plane, locked into a transitory relationship with the free magazine, you might start to wonder: what religion is this? Maybe you look around in the cabin to see if anyone else got so sidelined. Maybe you see someone turn their airline magazine pages quickly, barely registering the details; maybe you see someone else ripping out an article about ballpark food. And suddenly you decide that all of us have a relationship to consumer culture and its religion even if we claim no relationship to it at all. Religion isnt only something you volunteer to join, open-hearted and confessing. It is not only something you inherit, enjoined by your parents. Religion is also the thing into which you become ensnared despite yourself. Religion is one way to describe how we organize ourselves in the salespersons world.

Avi might say that his dancing public is nothing like the pious Israeli Jews who climb up to Masada before dawn so when the sun rises they can daven Shacharit (practice daily morning prayer). Scott could say his endorsement of Marilyns iconic face is nothing like the figurines enshrined at the nearby Tahl Mah Sah Buddhist Temple on West Olympic Boulevard or the icons at Christ the King Roman Catholic Church on North Rossmore Avenue. And I would agree: there are differences between people dancing and people praying; there are differences between celebrities and deities.

But I will argue that emphasizing these differences eclipses the possible hermeneutic territory opened by observing their commonalities. A scriptural law and a dance beat are not the same kind of thing, but they are both reminders of a certain authority. A scripture and an airline periodical are not the same thing, but they both present themselves as resolved about the world and who we might be in it. Much of the literature addressing religion in the modern period frets about whether we live in a time with fewer religious laws and too many dance beats, or too much tourism and too little pilgrimage (or vice versa). But one of the key assumptions of this book is that religion is a word that has captured our sociality. (Here the many valences of capture are intended.) Religion is a name for social organization. It doesnt matter if you have not seen the inside of a cathedral, a temple, or a seminary offering theological education. I claim that no matter what you think you are relative to some abstract notion of religion, you are, as a social actor, as a political actor, and as an economic actor, being determined by it.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).