PENGUIN

CLASSICS

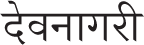

ROOTS OF YOGA

JAMES MALLINSON is Senior Lecturer in Sanskrit and Classical Indian Civilization at SOAS, University of London. His research focuses on the yoga tradition, in particular the texts, techniques and practitioners of traditional . He has edited and translated several texts on hahayoga from its formative period, the eleventh to fifteenth centuries CE, and published encyclopedia entries and journal articles on yogas history. His primary research methods in addition to philology are ethnography and art history. He has spent several years living with traditional Hindu ascetics and yogis in India and was honoured with the title of mahant by the Ramanandi Sampradaya at the 2013 Kumbh Mela festival. He is currently leading a five-year, six-person research project at SOAS on the history of hahayoga, funded by the European Research Council, whose outputs will include ten critical editions of key texts on hahayoga.

MARK SINGLETON is Senior Research Fellow in the department of Languages and Cultures of South Asia, SOAS, University of London, where he works with James Mallinson on the Indian and transnational history of hahayoga. He taught for six years at St Johns College (Santa Fe, New Mexico), and was a Senior Long-Term Research Scholar at the American Institute of Indian Studies, based in Jodhpur (Rajasthan, India). He was a consultant and catalogue author for the 2013 exhibition Yoga: The Art of Transformation at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC, and has served as co-chair of the Yoga in Theory and Practice Group at the American Academy of Religions. He is a manager of the Modern Yoga Research website. His research focuses on the tensions between tradition and modernity in yoga, and the transformations that yoga has undergone in recent centuries in response to globalization. He has published book chapters, journal articles and encyclopedia entries on yoga, several edited volumes of scholarship, and a monograph entitled Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice. His current work involves the critical editing and translation of three Sanskrit texts of hahayoga and new research on the history of physical practices that were incorporated into or associated with yoga in pre-colonial India.

Translated and Edited

with an Introduction by

James Mallinson and Mark Singleton

ROOTS OF YOGA

PENGUIN CLASSICS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

This edition first published in Penguin Classics 2017

Introductions, original translations and editorial material James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, 2017

All rights reserved

The moral right of the translators and editors has been asserted

Cover: tapkara asana (the ascetics posture). From a c.1830 illustrated manuscript of the Jogapradipaka The British Library Board

ISBN: 978-0-141-97824-6

Note on the Reference System and Diacritics

The translated passages are numbered sequentially from the beginning to the end of the book, and are referred to in the introductions by these numbers, which are given in bold type. In cases where the chapter arrangement is entirely chronological, the first number indicates the chapter and the second the translation itself. So, for example, 3.4 denotes Chapter 3, translation 4. In cases where the chapters are arranged thematically, the first number indicates the chapter, the second the thematic section, and the third the translation. So, for example, 6.2.1 denotes Chapter 6, section 2, translation 1.

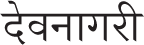

Historically, Sanskrit has been written using many different scripts. Since the advent of printing, the most common of these, especially in northern India, has been Devangar ( ). It is important to understand, however, that these scripts are not Sanskrit itself but systems for representing its sounds. The Roman alphabet (used for writing English and other European languages) cannot represent the full range of sounds in Sanskrit, and so we must add diacritical marks to certain letters. In this book we follow the conventions of the International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST), which allows for the lossless representation of the Sanskrit syllabary in Roman script.

). It is important to understand, however, that these scripts are not Sanskrit itself but systems for representing its sounds. The Roman alphabet (used for writing English and other European languages) cannot represent the full range of sounds in Sanskrit, and so we must add diacritical marks to certain letters. In this book we follow the conventions of the International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST), which allows for the lossless representation of the Sanskrit syllabary in Roman script.

Over the last three decades there has been an enormous increase in the popularity of yoga around the world. The United Nations recent declaration of an International Day of Yoga

In spite of yogas now global popularity (or perhaps, rather, because of it), a clear understanding of its historical contexts in South Asia, and the range of practices that it includes, is often lacking. This is at least partly due to limited access to textual material. A small canon of texts, which includes the Bhagavadgt, Patajalis Yogastras, the Hahapradpik and some Upaniads, may be studied within yoga teacher-training programmes, but by and large the wider textual sources are little known outside specialized scholarship. Along with the virtual hegemony of a small number of posture-oriented systems in the recent global transmission of yoga, this has reinforced a relatively narrow and monochromatic vision of what yoga is and does, especially when viewed against the wide spectrum of practices presented in pre-modern texts.

Of course, texts are not reflective of the totality of yogas development they merely provide windows on to particular traditions at particular times and an absence of evidence for certain Conversely, the appearance of new practices in texts is itself often an indication of older innovations. Despite these limitations, however, texts remain a unique and dependable source of knowledge about yoga at particular moments in history, in contrast to often unverifiable retrospective self-accounts of particular lineages. In addition to texts, material sources, particularly sculpture and painting from the second millennium CE, provide invaluable data for the reconstruction of yogas history. While we have not addressed such sources directly here, they have informed our analyses. Examples of our work with such sources can be found in Diamond 2013.

In some respects this book resembles a traditional Sanskrit nibandha (scholarly compilation) in that it gathers together a wide variety of texts on a single topic. Indeed, this collection benefits enormously from advances in historical and philological research in yoga ).

The yoga whose roots we are identifying is that which prevailed in India on the eve of colonialism, i.e. the late eighteenth century. Although certainly not without its variations and exceptions, by this time there is a pervasive, trans-sectarian consensus throughout India as to what constitutes yoga in practice. One of the reasons for this is the rise to predominance of the techniques of hahayoga, which held a virtual hegemony across a wide spectrum of yoga-practising religious traditions, including the The texts included in this collection reflect this historical development. As well as delimiting what would otherwise be an unmanageable amount of material, focusing on yoga as it was most commonly understood helps to reflect the actual practices of a majority of traditions in which yoga was undertaken. Such a focus can also help shed light on the immediate predecessors of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century yogis who helped disseminate yoga around the world.

CLASSICS

CLASSICS

). It is important to understand, however, that these scripts are not Sanskrit itself but systems for representing its sounds. The Roman alphabet (used for writing English and other European languages) cannot represent the full range of sounds in Sanskrit, and so we must add diacritical marks to certain letters. In this book we follow the conventions of the International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST), which allows for the lossless representation of the Sanskrit syllabary in Roman script.

). It is important to understand, however, that these scripts are not Sanskrit itself but systems for representing its sounds. The Roman alphabet (used for writing English and other European languages) cannot represent the full range of sounds in Sanskrit, and so we must add diacritical marks to certain letters. In this book we follow the conventions of the International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST), which allows for the lossless representation of the Sanskrit syllabary in Roman script.