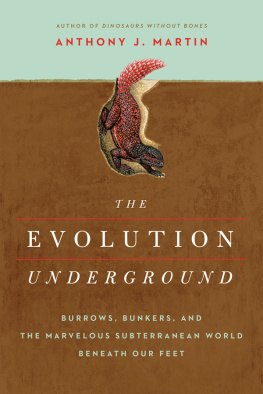

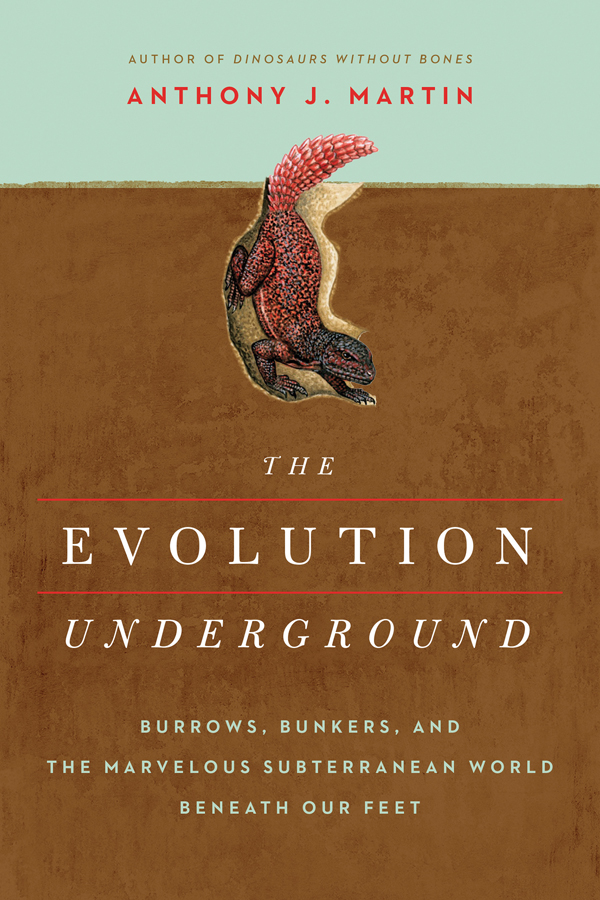

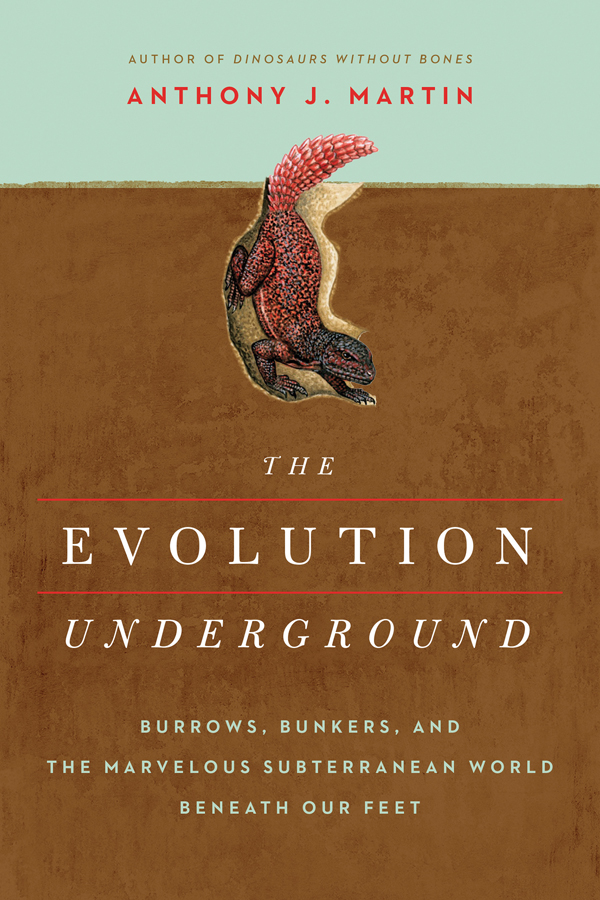

ALSO BY ANTHONY J. MARTIN

Dinosaurs Without Bones

THE

EVOLUTION

UNDERGROUND

BURROWS, BUNKERS, AND THE MARVELOUS

SUBTERRANEAN WORLD BENEATH OUR FEET

ANTHONY J. MARTIN

THE EVOLUTION UNDERGROUND

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 W 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2017 by Anthony J. Martin

First Pegasus Books cloth edition February 2017

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-312-4

ISBN: 978-1-68177-375-9 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company

To my mother, Veronica, who loved books.

To us, up is a good direction. Not so, or not necessarily so, to an ant. Up is where the food comes from, to be sure; but down is where security, peace, and home are to be found. Up is the scorching sun; freezing night; no shelter in the beloved tunnels; exile; death.

Ursula K. Le Guin (1974),

The Author of the Acacia Seeds and

Other Extracts from the Journal of the

Association of Therolinguistics

The Wondrous World

of Burrows

Into the Dragons Lair

The alligator den had a big surprise for us. Its occupant was hidden inside a dark space down an inclined tunnel, its entrance denoted by a meter-wide, half-moon-shaped hole in the middle of a pine forest. The alligators presence was verified only by a rumbling growl, followed by an openmouthed hiss. The burrow chamber added resonance to these sounds, turning an already spooky situation into a downright portentous one. This sonic combo, intended as a warning, worked quite well in that respect, persuading all of us to issue a collective Whoa!, take a few steps back, and assess our situation.

It was yet another moment in my teaching career when I wondered how many other professors must concern themselves with apex predators showing up in their classrooms. Nonetheless, on the plus side, if any of my students had been bored with the course material, they were now very much engaged, perhaps even wondering if this alligator-related incident would be covered on the next exam.

At that moment, my undergraduate students, a faculty colleague, and I were deep in the interior of St. Catherines Island on the Georgia coast and on our sixth day of a March 2013 spring-break field course to the Georgia barrier islands. St. Catherines is an undeveloped island used mostly for scientific research and the fifth island we had visited thus far on our trip. My colleague was geographer Michael Page, who had joined us the previous day; he had been on St. Catherines with me once before to map alligator dens in July 2012. During that time, we documented dozens of dens next to water bodies, many of which hosted alligators. In some instances, we affirmed the identity and purpose of these big holes by witnessing alligators swimming or otherwise dashing into them. With other dens, we spotted tracks and tail-drag traces crisscrossing their entrances, effectively telling us not to get any closer.

This den, though, had no such fresh warning traces outside of it, meaning the contentious alligator inside had been there for a while. When the growl-hiss greeting broadcast from the den, Michael was standing above and behind the den, whereas I was almost directly in front. We had already seen about ten alligator dens that morning, all of them empty. This lulled us into a false sense of security, a confirmation bias that affected our better judgment when approaching this one. My prejudice was further bolstered by a memory of this very same burrow, which had had absolutely no sign of an alligator in it when Michael and I had examined it the previous summer. During that visit, we photographed and measured each den we encountered, as well as recorded their locations with a global positioning system (GPS) unit. But we remembered this specific den because it had the largest entrance of any we had seen, at more than a meter (3.3 feet) wide and 40 centimeters (16 inches) tall. It was big enough that I could have crawled into it, had I been so stupid.

Size aside, what really made this den memorable was its location, which was in the middle of the woods. As everyone should know, alligators normally live in water. Yet no lakes, ponds, or streams were within sight, and the forest floor around the den was carpeted with dry pine needles. Still, this den and several others nearby were located on the bank of what used to be a human-made canal. Thus Michael and I quite reasonably surmised the canal had been submerged sometime in the pastperhaps decades agowhich encouraged alligators to move into the neighborhood and dig dens. Later, drought and other changes in local hydrology must have altered the water supply in this area. So just as in any area where humans lack the basic means for survivallike nearby coffee shops offering pumpkin-spice lattes and free wi-fithe alligators moved somewhere else.

In this instance, I had just begun explaining to our students how this was yet another example of an abandoned den made by previous generations of now-dead alligators. This meant it only served as the trace of a former alligator in what used to be an aquatic environment that later turned into a terrestrial environment. A fine hypothesis it was, but one so rudely proven wrong by the live, two-meter-long, body-armored, and bad-tempered saurian residing in its so-called abandoned home.

To my students credit, they had started us on the path to falsifying the notion that this big hole was gator-less. Once spotted, I greeted it like an old friend, enthusiastically striding toward its opening before delivering my little lecture to the assembled group. A few students stood back, impressed by the size of the hole and staring into its underground darkness, a seemingly bottomless pit of mystery. The whirring of zoom lenses and digitally rendered shutter sounds behind me told me they were taking plenty of pictures. I was pleased that they found this burrow as interesting as I did.

Suddenly, I was jarred out of my educational reverie when one of students said, I see teeth in there.

Teeth? I asked.

Yeah, she said, and others nodded agreement. She was looking into the den, while two others looked anxiously back and forth between their camera view-screens and the den, testing what they either observed or imagined.

What kind of teeth? I asked. Like a typical paleontologist, I was thinking of a disembodied skull or jaw, instead of a breathing animal bearing (or baring) those teeth.

I dont know. Could it be a snake?

Sure, thats possible. I had seen alligator dens with snakes in them before. Also, unlike certain fictional archaeologists, I like snakes and relished the thought that one might be in the burrow. But you probably wouldnt be seeing its teeth, I said, as I became more confused about this unexpected shift in the lesson plan for my students. Puzzled, I stepped closer to the entrance, which is when I received an admonition from their classmate who had somehow (but understandably) made it past the registrar without paying tuition.

Next page