To my parents,

who are always there for me

on the surface

Nature loves to hide.

HERACLITUS, Fragments

CHAPTER

DESCEND

There is another world, but it is in this one.

PAUL LUARD

F ind signs of it everywhere you go. Step out your front door and feel beneath your feet the thrum of subway tunnels and electric cables, mossy aqueducts and pneumatic tubes, all interweaving and overlapping like threads in a great loom. At the end of a quiet street, find vapor streaming out of a ventilation grate, which may rise from a hidden tunnel where outcasts dwell in jerry-rigged shanties, or from a clandestine bunker with dense concrete walls, where the elite will flee to escape the end of days. On a long stroll through quiet pastureland, run your hands over a grassy mound that may conceal the tomb of an ancient tribal queen, or the buried fossil of a prehistoric beast with a long snaking spine. Hike down a shaded forest trail, where you cup your ear to the earth and hear the scuttle of ants excavating a buried metropolis, spoked with tiny whorled passageways. Trekking up in the foothills, you smell an earthy aroma emanating from a slender crack, the sign of a giant hidden cave, where the stony walls are graced with ancient charcoal paintings. And everywhere you go, beneath every step, you feel a quiver coming up from deep, deep below, where titanic bodies of stone shift and grind against one another, causing the planet to tremble and shudder.

If the surface of the earth were transparent, wed spend days on our bellies, peering down into this marvelous layered terrain. But for us surface dwellers, going about our lives in the sunlit world, the underground has always been invisible. Our word for the underworld, Hell, is rooted in the Proto-Indo-European kel-, for conceal; in ancient Greek, Hades translates to the unseen one. Today, we have newfangled devicesground-penetrating radar and magnetometersto help us visualize the underground, but even our sharpest images come out distant and foggy, leaving us like Dante, squinting into the depths: so dark and deep and nebulous it was, / try as I might to force my sight below / I could not see the shape of anything. In its obscurity, the underground is our planets most abstract landscape, always more metaphor than space. When we describe something as undergroundan illicit economy, a secret rave, an undiscovered artistwe are typically describing not a place but a feeling: something forbidden, unspoken, or otherwise beyond the known and ordinary.

As visual creaturesour eyes, wrote Diane Ackerman, are the great monopolists of our senseswe forget about the underground. We are surface chauvinists. Our most celebrated explorers venture out and up: we have skipped across the moon, guided rovers into Martian volcanoes, and charted electromagnetic storms in distant outer space. Inner space has never been so accessible. Geologists believe that more than half of the worlds caves are undiscovered, buried deep in impenetrable crust. The journey from where we now sit to the center of the earth is equal to a trip from New York to Paris, and yet the planets core is a black box, a place whose existence we accept on faith. The deepest weve burrowed underground is the Kola borehole in the Russian Arctic, which reaches 7.6 miles deepless than one half of one percent of the way to the center of the earth. The underground is our ghost landscape, unfolding everywhere beneath our feet, always out of view.

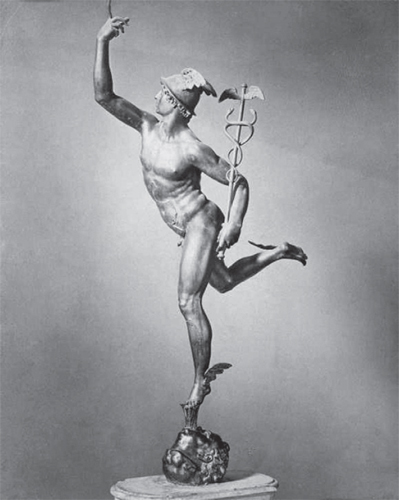

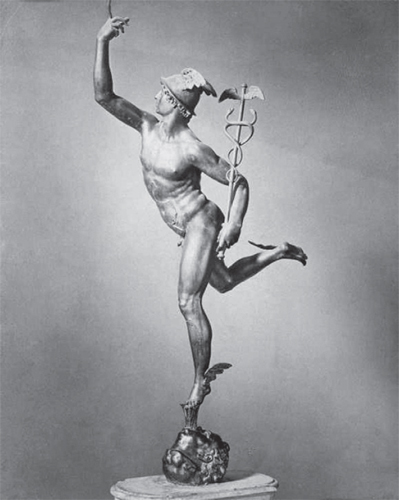

But as a boy, I knew that the underworld was not always invisibleto certain people, it could be revealed. In my parents old edition of DAulaires Book of Greek Myths, I read of Odysseus, Hercules, Orpheus, and other heroes who ventured down through craggy portals in the earth, crossed the river Styx on Charons ferry, gave the slip to three-headed Cerberus, and entered Hades, the land of shades. The one who most captivated me was Hermes, the messenger god, he of the winged helmet and sandals. Hermes was the god of boundaries and thresholds, and the guide of the souls of the dead into Hades. (He bore the marvelous title of psychopomp, which means soul conductor.) While other gods and mortals obeyed the cosmic boundaries, he swooped openly between light and dark, above and below. Hermeswho would become the patron saint of my own underground excursionswas the one true subterranean explorer, who cut through darkness with clarity and grace, who saw the underworld, and knew how to retrieve its buried wisdom.

The summer I turned sixteen, when my world felt as small and known as the tip of my finger, I discovered an abandoned train tunnel running beneath my neighborhood in Providence, Rhode Island. Id heard about it first from a science teacher at school: a small, whiskery man named Otter, who knew every secret groove in every landscape in New England. The tunnel had once served a small cargo line, hed told me, but that was years ago. Now it was a ruin: full of mud and garbage and stale air and who knew what else.

One afternoon, I found the entrance, which was concealed under a thicket of bushes behind a dentists office. It was wreathed in vines and had the date of its construction1908engraved in the concrete above its mouth. The city had sealed the entrance with a metal gate, but someone had sliced open a small passageway: along with a few friends, I climbed underground, our flashlight beams crisscrossing in the dark. The mud sucked at our shoes and the air was boggy. On the ceiling were clusters of pearly, nipplelike stalactites that dripped water down on our heads. Halfway through, we dared one another to switch off our lights. As the tunnel fell to perfect darkness, my friends whooped, testing the echo, but I held my breath and stood dead still, as though, if I moved, I might float right off the ground. That night at home, I pulled up an old map of Providence. I started with my finger where wed entered the tunnel and moved to where it opened at the other end. I blinked: the tunnel passed almost directly beneath my house.

That summer, on days when no one else was around, Id put on boots and go walking in the tunnel. I couldnt have explained what drew me down, and I certainly never went with any particular mission. Id look at the graffiti or kick around old bottles of malt liquor. Sometimes Id turn off my light, just to see how long I could last in the dark before my nerves started to bristle. To the extent that I was aware of myself at all, as a sixteen-year-old I sensed that these walks were outside of my character: I was an uncertain teenager, scrawny, gap-toothed, with librarianish glasses. When my friends were starting to make out with girls, I still had a terrarium of pet tree frogs in my bedroom. I read about other peoples adventures in books, without ever thinking to embark on my own. But something about the tunnel got under my skin: Id lie in bed nights just imagining it running under the street.

At the end of that summer, following a heavy rainstorm, I had just climbed beyond the threshold of the tunnel when I heard an unexpected rumble coming from the darkness ahead. Alarmed, I started to turn back, but decided to keep walking, even as the sound grew. Deep in the tunnel, I found the source: a crack in the ceilinga burst pipe, maybe, or a leakfrom which water was pouring down in cascades. Directly beneath the falling water, I saw an overturned plastic beach pail. Then a paint bucket. Then, all at once, an enormous assembly of overturned containersoil drums, beer cans, Tupperware, gas canisters, coffee tinsall in a giant cluster, arranged under mysterious circumstances by a person Id never meet. The water drummed down on the vessels, sending up an echoing song, as I stood in the dark, nailed to the floor.