To four persons who, like Hildegard, fought the good fight to awaken church and society in their lifetimes:

Sr. Marjorie Tuite, O.P.

Bob Fox

Ken Feit

Tony Joseph

And to Jose Hobday, who is still doing so.

INTRODUCTION

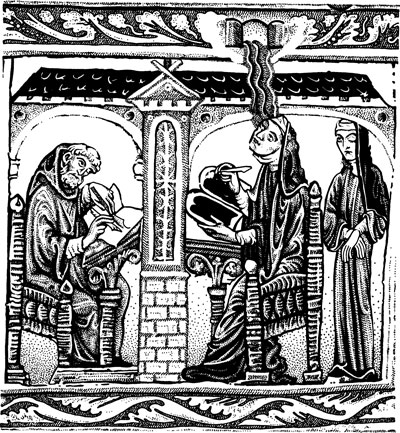

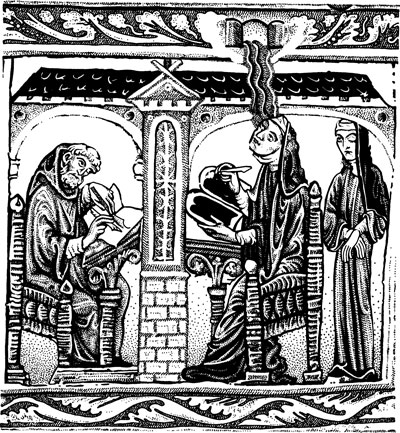

Hildegard of Bingen has been called an ideal model of the liberated woman who was a Renaissance woman several centuries before the Renaissance. There is much truth to these statements, for Hildegard was indeed a woman of tremendous stature and power who used her gifts to the utmost. Her interests and accomplishments include science: her books explore cosmologystones, rocks, trees, plants, birds, fishes, animals, stars and winds. They include music: her opera, Ordo Virtutum, is on record and has been playing live by a European group called Sequentia in both Europe and North America, and she wrote about seventy other extant songs. They include theology: her book Scivias is a study of biblical texts and ecclesial practice combined with personal insight and criticism. They include painting: Scivias, for example, contains thirty-six renditions of her images or visions. They include healing at the personal level: she writes of the appropriate herbs and remedies for psychic and physical ailmentsand at the social level: many of her sermons and letters, in particular, take on issues of social disease and injustice. Hildegard was painter and poet, musician and healer, theologian and prophet, mystic and abbess, playwright and social critic. Her life (10981179) spanned four-fifths of the twelfth centurya century of amazing creative and intellectual achievement in the West. She contributed substantially to the awakening to a living cosmology and to the influx of womens experience into the mystical literature of the West.

Hildegards Life Briefly Summarized

At the confluence of the Nahe and Glan rivers, very near their outlets into the Rhine River, is found a pre-Christian spiritual site that became known as Disibodenberg in the time of Hildegard. It derives its name from Saint Disibode, one of the Celtic monks and missionaries from Scotland or Ireland who lived as a hermit at this mountain in the seventh century. By the ninth century, he was already honored as a saint in the diocese of Mainz. The first monastic foundation in the area can be dated to about the year 1000, when the site was home for a religious foundation of twelve priests who served the people of the surrounding areas. Archbishop Ruthard (10891109) brought the Benedictines of the Cluny reform to the site and managed to wrestle the monastery from the dominance of the nobility to the direct control of the bishop. While the first generation of monks did not succeed in their efforts to establish a community (1098), the second group was successful eight years later. The Archbishop appointed the Abbot of St. Johns in Mainz to head the new community and the first monastic buildings were begun in 1108. A womens cloister was part of this monastery from the first (1106), and in 1112 Jutta of Spanheim was given leadership of this community of noble women.

It was in 1106 that Hildegards parents, having offered her to God as a gift and maybe even a tithefor she was the tenth of ten childrenput her into the hands of Jutta, who was then living an eremetical life adjacent to the monastery. Under Juttas tutelage, Hildegard studied and matured into the amazing woman she was to become. On Juttas death in 1136, Hildegard was chosen to lead her community. Hildegards most controversial decisionin addition, of course, to her vast writing and preachingwas to leave the famous Disibode monastery with all of her sisters and with all of their dowries. What drove her to this decision, a decision that she had to defend for the next twenty-seven years? There was friction between the local nobilityto whom she owed a certain allegianceand the bishop, but also the monks were returning to pre-Cluny privileged practices, such as the use of stewards as administrators and bailiffs to handle their vast properties. In addition, Hildegards fame from her first and very successful book, Scivias, drew more and more women to study and live with her and the male community members seemed reluctant to move over and give the womens community the space it needed. Hildegard left Disibodenberg in 1147, and in 1151 she and her sisters moved into a new cloister built for them in Rupertsberg near todays town of Bingen. There, Hildegard lived as abbess and wrote poems and hymns and even a modest-sized biography of St. Disibode, praising him for his love of monasticism and subtly critiquing the Archbishop of Mainz and the Emperor Frederich Barbarossa by implication. Hildegards warnings to the monks of Disibodenberg about their privileges and wealth did not, alas, go heeded. Armed battles were fought between monastic and episcopal supporters there in the thirteenth century, and the monastery was actually converted into a fortress. By the mid-thirteenth century, the monastic buildings were in ruins and the Benedictine morale was in an equally sad state. Disibodenberg was never resurrected.

Unfortunately, Hildegard has been far less celebrated since her lifetime than during it. The letters in the present volume give ample evidence of her immense influence with all strata of society from monks and popes to emperors and kings and queens, from lay persons and religious sisters to bishops and social changers. Until Bear & Company published their first book of Hidegards writings in 1982, Meditations with Hildegard of Bingen, she was never translated into English except for a few pages in a book printed in 1915. Bear has since brought out my book on Illuminations of Hildegard ofBingen and the text of her first book, Scivias. Now this present volume allows us once again to cease our learned ignorance of one of the greatest intellectuals and mystics of the West. For in this book, we have brought together the most significant portions of her greatest cosmological work, De operatione Dei, and the most significant of her letters and sermons, and twelve representative poems and songs.

Why would the work of a twelfth-century abbess be of interest or concern for those of us preparinghopefullyto usher in a twenty-first century and a third millenium? In many respects, the work of Hildegard in the texts presented in this book answers that question directly.

De operatione Dei

In the first text of this volume, that of De operatione Dei (The Book of Divine Works), Hildegard offers western civilization a deep and healing medicine for what may well be its number-one disease of the past few centuries: anthropocentrism. The Wests preoccupation with the human, its terrible and expensive ignoring of other creatures and natures cycles, its reduction of the mystery of the universe to a machine, has brought us to the point of Earth-murder. And this even without a nuclear holocaust taking place. Hildegard is a prophet to our day because she lays out the possibility of, and therefore hope for, a living cosmology. According to the twentieth-century psychologist Otto Rank, the most basic neurosis of our species in this century has been the divorce of religion from a cosmology. When religion lost the cosmos in the West, he remarks, society became neurotic and we had to invent psychology to deal with the neurosis. The post-Newtonian worldview in physics and in religion is awakening the West to a living cosmology once again. But Hildegard shows us how this awakening will come about and take shape. Her great gift is a cosmological gift in a time of excessive attention rendered to human affairs alone.

Next page