1. Introduction

The phenomenon of religious belief poses many interesting and challenging questions: Those who dont have the privilege of believing in miracles, divine providence, or resurrection often find it difficult to understand the meaning of religious concepts in a society characterized by a primarily scientific paradigm in fields like economy, technics, justice, or politics. A number of questions concerning religious belief seem to have puzzled also Ludwig Wittgenstein and he came up with interesting questions and answers to this effect. His concept of hinge beliefs, if applicable to religious belief, is a surprising and convincing explanation of the phenomenon of religious belief. But can it really be applied to religion and did Wittgenstein do that? This paper will try to find answers to these questions.

Here are a number of questions pertinent to religion to which Wittgenstein indirectly responded:

a) Are religious beliefs comparable to the hinge beliefs of a secular world-picture?

b) How can a religious world-picture coexist with the scientific world-picture which dominates todays politics, economics and jurisdiction?

c) How is a religious belief acquired?

d) What exactly do the faithful believe, what do they know and what do they feel certain of?

e) What is the relation between religious belief and the conduct of ones life?

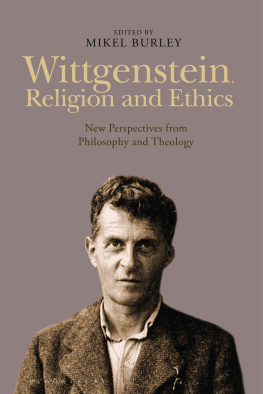

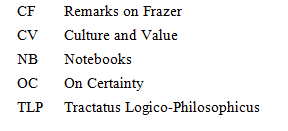

Wittgensteins attitude towards religion has significantly changed in the course of his life, from his childhood in one of the richest and most influential families of Vienna to his voluntary engagement in World War I and, finally, to his late philosophy. This paper is looking at religious belief primarily from the perspective of Ludwig Wittgensteins latest work, posthumously edited under the title of On Certainty. Wittgenstein comes up with interesting insights into the philosophy of knowledge, belief, trust, doubt, and certainty. Moreover, Wittgenstein s wrestling with religious belief and world-picture also underlines and enhances his epistemological thinking, as Michael Kober puts it: Wittgenstein's peculiar account of religion improves our understanding of epistemic certainty. (Kober 2007: 225)

In order to set the scene for Wittgensteins reflections in On Certainty, I shall first briefly look at the development of his own attitude to religious belief as documented in his Notebooks and other sources.

In the following section I shall describe religious terms and phenomena as they appear in On Certainty.

Then I shall match appropriate aphorisms of On Certainty with the questions mentioned above and thus distill possible answers by Wittgenstein to the questions. Ill argue that religious beliefs are hinge beliefs in Wittgensteins sense and that his concept of hinges opens an opportunity to better understand world-pictures different from ones own.

Finally, I shall comment my findings from the epistemological point of view.

2. Wittgensteins Relation to Religious Belief

Born into a family of Jewish descent, baptized and educated in Roman Catholic fashion and influenced by Protestant as well as agnostic members of his family, Wittgenstein was puzzled, inspired, and almost tortured for his whole life by very high ethical demands on himself and his conduct of life without ever practicing anything that would have been near to a religious life. He appeared to crave for relief from his weaknesses; that is, in religious terms, for redemption (Kober 2007: 244).

Frederick Sontag adds the following characterization of Wittgensteins presumed inner conflicts: Philosophy, intellect, simplicity, ascetic practice and the search for love, all fought continually as competing goals in Wittgensteins mind and soul, and they did so without resolution. (1995: 128). Other than Leo Tolstoy, however, whose book The Gospel in Brief was for some time during World War I his preferred and almost revered reading, Wittgenstein did not revert to a religious life.

During World War I, when he voluntarily served in the Austrian army in often life-threatening positions at the front line, we can see from his notebooks that belief in God was not completely distant or alien to him.

On July 6th, 1916, he wrote in his Notebooks (1914-1916):

The meaning of life, i.e. the meaning of the world, we can call God. And connect with this the comparison of God to a father. To pray is to think about the meaning of life. (NB, 73e)

A few years later, in his first book, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, there was little space left for religious thoughts. God does not reveal himself in the world (TLP: 6.432) is one of the few references to be found. We can assume, however, that this was not because he had entirely lost interest in religion, but because the matter was outside the scope of the book. In the narrow definition of meaningful discourse he is advocating in the Tractatus, religious language does not get so far as to be false (Clack 1999: 28). In that interpretation of meaning, Wittgenstein considered religious beliefs neither to be true nor false, he signified them to be senseless (cf. ibid.).

Gradually, Wittgenstein developed a more distanced attitude towards religion, which Brian R. Clack characterizes as follows: Religion is not grounded in rationcination, but is, rather, something like a way of responding to the world, a mode of orientation, or a way of living in the world. (1999: 65 f).

In his last years he was using religious as well as mythical matters more metaphorically, to exemplify his epistemological considerations. Before we can draw conclusions concerning religion from his aphorisms, we must prepare the stage with some epistemological deliberations.

3. Considerations Pertinent to Religion in On Certainty

On Certainty is not a book about religion, or religious belief. It deals, however, with many topics that are relevant also for religion. Knowing and believing, doubt and certainty, world-picture, language games, acting, mysticism and mythology, and, finally, God are concepts alluded to in the book. Together, they help to clarify some aspects of Wittgensteins attitude towards religion.

Knowing and Believing

Does a religious believer know about God or does he just believe in his existence and properties? That is a question which probably is not a concern of believers, but it is important for a philosophical, epistemological understanding of religious belief.

He knows vs. I know

In OC 13 Wittgenstein explains the difference between he knows, which implies knowledge, and I know which only expresses my conviction, but not necessarily knowledge, as long as I have not provided satisfactory justification for it:

For it is not as though the proposition "It is so" could be inferred from someone else's utterance: "I know it is so". Nor from the utterance together with its not being a lie. - But can't I infer "It is so" from my own utterance "I know etc."? Yes; and also "There is a hand there" follows from the proposition "He knows that there's a hand there". But from his utterance "I know..." it does not follow that he does know it. (OC 13)

As a consequence of the rule that knowledge requires justification, Wittgenstein adds: "What is the proof that I know something? Most certainly