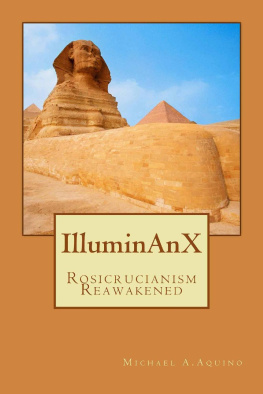

THE

ROSICRUCIANS

The History, Mythology, and

Rituals of an Esoteric Order

Christopher McIntosh

First paperback edition published in 1998 by

Weiser Books, an imprint of Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC

with offices at

500 Third Street, Suite 230

San Francisco, CA 94107

www.redwheelweiser.com

Third Revised Edition Copyright 1997 Christopher McIntosh

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Red Wheel/Weiser. Reviewers may quote brief passages. Material quoted in this book may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright owner.

ISBN-10: 0-87728-920-4

ISBN-13: 978-0-87728-920-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

McIntosh, Christopher

The Rosicrucians : the history, mythology, and rituals of an esoteric order /

Christopher Mclntosh.Rev. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Rosicrucians. I. Title.

BF1623.R7M35 1997

135.43'09'3dc21

97-8592

CIP

Typeset in 10 pt Cheltenham

Printed in the United States of America

MG

13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American

National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library

Materials Z39.48-1992(R1997).

Venerable Brotherhood, so sacred and so little known, from whose secret and precious archives the materials for this history have been drawn; ye who have retained, from century to century, all that time has spared of the august and venerable science. Many have called themselves of your band; many spurious pretenders have been so called by the learned ignorance which still, baffled and perplexed, is driven to confess that it knows nothing of your origin, your ceremonies or doctrines, nor even if you still have local habitation on the Earth.

Edward Bulwer-Lytton

Zanoni, page 165.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATRATIONS BETWEEN PAGES 8 AND 9

FOREWORD

In 1895, W. B. Yeats wrote an essay titled The Body of the Father Christian Rosencrux, which begins by describing how the founder of Rosicrucianism was laid in a noble tomb, surrounded by inextinguishable lamps, where he lay for many generations, until he was discovered by chance by students of the same magical order. Having said this, Yeats goes on to attack modern criticism for entombing the imagination, proclaiming that the ancients and the Elizabethans abandoned themselves to imagination as a woman abandons herself to love, and created beings who made the people of this world seem but shadows

On the whole, Yeats' use of the image of Christian Rosenkreuz seems irrelevant until the reader comes to this sentence: I cannot get it out of my mind that this age of criticism is about to pass, and an age of imagination, of emotion, of moods, of revelation, about to come in its place; for certainly belief in a supersensual world is at hand. In this statement, Yeats shows his own deep understanding of the whole Rosicrucian phenomenon. That is what it was really about; that is the real explanation to reverberate down three-and-a-half centuries.

The hoax beganas Christopher McIntosh describes in these pageswith the publication, in 1614, of a pamphlet called Fama Fraternitatis of the Meritorious Order of the Rosy Cross, which purported to describe the life of the mystic-magician Christian Rosenkreuz, who lived to be 106, and whose body was carefully concealed in a mysterious tomb for the next 120 years. The author of the present book translates fama as declaration, but my own Latin dictionary defines it as common talka report, rumour, saying, tradition. So it would hardly be unfair to translate fama as myth or legend.

At all events, this mysterious pamphlet (which can be found printed in full as an appendix to The Rosicrucian Enlightenment by Frances Yates) goes on to invite all interested parties to join the Brotherhood, and tells them that they have only to make their interest knowneither by word of mouth or in writingand the Brotherhood will hear about it, and probably make contact. This is, in itself, a suggestion that the Brotherhood has magical powersperhaps some crystal ball that will enable them to tune in to anyone who is genuinely interested.

Two more works followed the pamphletas Mr. McIntosh re-latesand many people took the trouble to publish replies, indicating their eagerness to join the Brotherhood. No one, as far as The land of heart's desire was about to become a reality.

Christopher McIntosh suggests, very plausibly I think, that the first two pamphlets were probably a joint effort of a group of idealistic philosophers based in Tbingen, perhaps inspired by an early novel by one of their number, Johann Valentin Andreae. This novel, The Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosencreutz, was published as the third Rosicrucian document in 1616.

All of this raises interesting questions: Why did the Brotherhood ask for volunteers and recruits if they had no intention of replying? If the authors of these documents were idealistic, then what was the ultimate aim of the whole exercise?

The main clue to the answer, I believe, lies in a phrase in Johann Andreae's will, made in 1634, when he was 48. Andreae writes: Though I now leave the Fraternity itself, I shall never leave the true Christian Fraternity, which beneath the Cross, smells of the rose, and is quite apart from the filth of this century. The filth of this century; this filthy centuryeither phrase might have been used by W. B. Yeats if his language had been a little more emphatic.

In his autobiography, Yeats says that Ruskin once remarked to his father that, as he made his daily way to the British Museum, he saw the faces around him becoming more and more corrupt. Untrue of course: people don't really change that muchor that fast. But Ruskin's words express the hunger of a man who feels that he lives in an age when no one really cares about the things that matter. T. S. Eliot expressed the same feeling in The Waste Land and The Hollow Men. The invention of Christian Rosenkreuz is, likewise, not so much a hoax as a cry of rejection and a demand for new ways : in short, a kind of prophecy.

It is worth noting that there are apparently two kinds of legend that seem to exercise great fascination over the minds of men. The first involves wickedness or horrorFaust, Frankenstein, Dracula, Sweeney Todd, even Jack the Ripper. The second involves, not so much goodness as greatness, superhumanity; and this can be found in legends of Hermes Trismegistos, King Arthur, Parsifal, and Merlin, as well as the modern Superman and Batman comic strips. In Yeats later remarked that he joined the Theosophical Society because he wanted to believe in the real existence of the Old Jew or his like.

For, of course, both the magical organizations to which Yeats belongedthe Theosophical Society and the Golden Dawndrew a leaf out of Pastor Andreae's book, and set out to build their organizations on a myth propagated as reality. Madame Blavatsky claimed to be in communication with Secret Masters in Tibet. And the story behind the Golden Dawn was at least as circumstantial as the account of the life of Rosenkreuz. In 1885, according to this story, a clergyman named Woodford was rummaging through the books in a secondhand stall in Farringdon Road when he came across a manuscript written in cipher; a friend, Dr. William Wynn Westcott, identified the cipher as one invented by a 15th-century alchemist, Trithemius. It proved to contain five magical rituals for introducing newcomers into a secret society. In the manuscript, there was also a letter which stated that anyone interested in the rituals should contact a certain Fraulein Sprengel in Stuttgart. It was Fraulein Sprengel, the representative of a German magical order, who gave Westcott permission to found the Golden Dawn.